101 Diagrams: My Test Kitchen Results

When I started to write a book about diagramming, I was hesitant to provide specific instruction on making any one type of diagram, and wanted to focus on teaching the reader how to think diagrammatically instead.

This way of thinking felt eerily like teaching someone to to cook. When we learn to cook, we learn to use what we have at hand to satisfy the goal, whether that is satiation or pleasure or using something before it spoils. Once we know how to cook, the recipes become less a guide and more just inspiration to include in our own process.

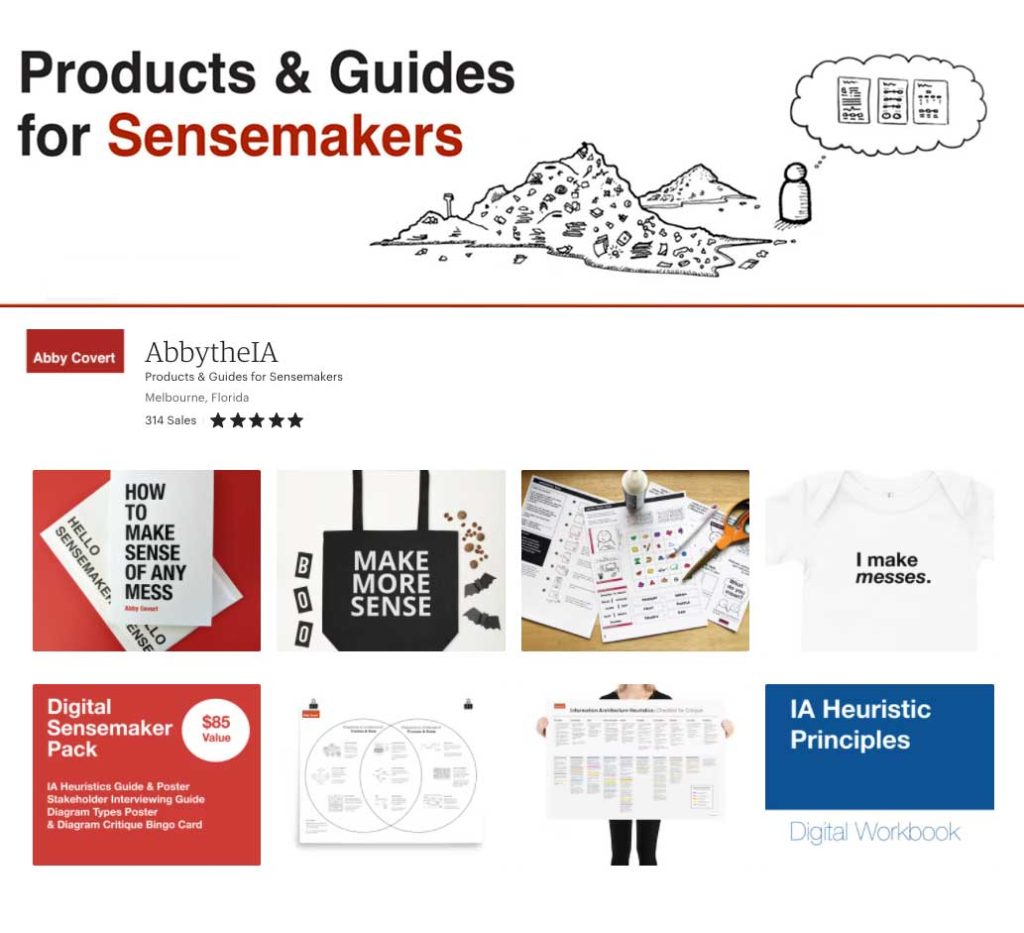

In my first book, How to Make Sense of Any Mess, I included ten common diagrams (fondly known as the pizza diagrams) without giving the reader even the smallest of clues about how to go about making anything that remotely resembled the examples that I provided.

For many readers this was not a barrier. They had made diagrams before and seen diagrams that looked like the examples shown. They knew how to start, and what to do. In short, they already knew how to cook…er, diagram.

But for many readers, especially those for whom diagramming is new or exposure to various diagram types has been limited, the distance between seeing a picture of a diagram and making something like it in their own context was a major barrier to putting the diagram part of that book to good use.

This insight came to a head for me early in the writing process when I was discussing this quandary with a friend and blurted out :

“It’s like if my cooking teacher had shown me a picture of a chocolate soufflé and then expected us to just be able to make one”

Once I said it, I could not take it back.

I knew my next book had to teach readers how to actually make those common types of diagrams, not just show pictures of diagrams readers might make if only there was a recipe for them to follow.

I created a cookbook of diagrammatic recipes that take a set of common diagrams found across fields of study and breaks each down into a recipe to be followed step-by-step using the reader’s unique context.

This cookbook will be included in the back of STUCK as a helpful guide for common forms diagrams take and how to practice making each.

…a diagrammatic test kitchen was born

To make sure this diagrammatic recipe idea was just wild enough to work, I recruited recipe testers for what I called my diagrammatic test kitchen. The ask was to participate in a self-paced activity testing two recipes in their own context.

To be honest, when I hit send on the email asking for help from my mailing list, I expected maybe a handful of people to sign up. I even had a plan B to ask past colleagues to fill in if I didn’t have enough interest.

What happened instead was I got the kindest responses of time and feedback from over 50 testers working either individually or in groups. Recipe testers made 101 diagrams using my recipes.

Top 3 Themes from Overall Feedback

I have a lot of work ahead iterating on the cookbook (and the rest of the book for that matter) based on this activity. It was equal parts eye-opening on the details I missed and reassuring on the concepts and tips that I got right. Also so MANY spelling errors to fix. Sigh.

As I come up for air after reading all the comments that testers left, I wrote the below to capture and share some of the highest level feedback that I am taking the most to heart coming out of this activity.

#1 Experienced sensemakers remembered the power of diagrams for helping others

I was thrilled to see many of the more experienced sensemakers step-up to test recipes they were familiar with, but with their less experienced colleagues. Their feedback indicated to me how helpful it was in some cases to remember how powerful diagrams are through the eyes of a beginner. I also think the basic nature of these recipes helped some sensemakers rediscover a little of the magic of diagrams when used to communicate with others.

“…the diagram really accelerated the junior developer’s understanding. What could have easily been a 40 minute conversation was done in about 10.”

#2 Diagrams allows deeper exploration of seemingly known things

When teaching diagrams, I often talk about the danger of staying in our heads and how diagrams can get us out of our head where we can make more progress on hard things.

I generally use the mind monster example, where something is so much bigger and more complex in our head than it actually is. I love to point out the anxiety that can be reduced when we get it onto paper, and start to see it as manageable and not so scary.

This research in the test kitchen clued me into the same being true (maybe even more true!) but for things you are ignorant of but have convinced yourself that you already know too well to look deeper.

In many cases the testers regalled stories of surprising themselves by diagramming things they thought they knew well, or were even in the position of having to communicate to others, only to discover a lot more questions for themselves than answers.

“I didn’t actually know how to organize the concepts I’ve presented — I realized that I might not understand the concepts as well as I thought I did.”

#3 People want examples of examples on examples about examples

I have a theory that if I provided an example for every statement in this book, or made a book about diagrams that was in fact entirely examples, people would still say they want more examples. It was unsurprisingly common feedback in this study. In fact, the word example appeared almost 100 unique times in a study with less than half as many respondents.

A common theme is wanting more complex examples. Someone cheekily suggested a “Olympic-Sized Swim lane Recipe” perhaps be included. Don’t get me wrong, most of these suggestions are not unwarranted, in fact I already started to make an Olympic size swim lane (spoiler alert!).

There is a lot of truth about diagrams in the statement: If you can see it, you can be it.

For this researcher though, this was one of those moments where I have to read between the lines and not just think about what the reader wants, which they think are more complex examples, when what I read in their responses was actually projecting a need for more reassurance as things get more complex.

When complex challenges come our way, we can make the common mistake to mistrust the simple tools at our fingertips and instead long for a perfect and complex enough example of a diagram that no one has ever made before. It is not always, but often the case that the same time could have been better spent just making a dang diagram.

I also think that this line of thinking comes down to a perception of right and wrong or good and bad that often gets put on this kind of squishy work. Let me assure you that no one is ever running any contests for the diagram that most closely followed all the arbitrary rules of diagramming.

Diagrams are meant to help the people who made them and the people they are made for. Its that simple, there are no diagram authorities to clear things with when you go off recipe.

And more … there is no perfect diagram. If you asked five experienced diagrammers to all make a journey or a block or a flow for the same audience and set intention, those would be 5 unique diagrams, each likely highlighting something else entirely.

Interestingly, I found in the feedback from testers that often when asking for more examples it turned out testers didn’t actually feel they needed more examples for themselves. There were many a sensemaker who wanted more examples to help out other sensemakers with less experience.

“Part of me wants a little more explanation or examples, but my gut tells me you are striking the right balance. BUT…I wonder if less experienced people would be helped by more examples?”

“I worry that just one or two simple visual examples create a mental model in newer diagrammers for what these diagrams can and should look like.”

What’s Next for the Cookbook?

I am through the overall feedback on the activity part of my analysis, and I am jumping into the wild world of recipe edits based on the discrete points of feedback from readers.

- Common Diagramming Questions Post: I am planning another post answering some common diagrammatic questions that came up in this activity so stay tuned for that in the coming weeks.

- Diagrammatic Sommelier Poster: As part of this activity, testers helped fine tune a decision tree diagram I have been working on to help answer the important question: What kind of diagram should I make? I loved the feedback from testers, and also the resounding message that I should get this piece into people’s hands ahead of the book. So stay tuned for a forthcoming poster and digital download in my Etsy shop this fall.

- Diagram Gallery: On testers suggestions, I am interested in creating a repository of diagrams created by readers organized by type. I would love for readers to share their own examples in a clear and useful way for other readers to learn from. If anyone has a tooling suggestion for managing that kind of workflow, please reach out!

Oh and if reading this made you wish you had the chance to have been involved in my test kitchen, make sure you join my email list.

Thank You, Recipe Testers!

This activity reminded me that writing a book takes a village. Thanks for all the helping hands, fellow villagers. And specifically thank you to these recipe testers who helped this round:

- Amanda Costello

- Amy Silvers

- Andres Holguin

- Andrew Maier

- Anna Kruse

- Chiara Grimandi

- Chris Barnes

- Claire Blaustein

- David Nicholson

- Devin Soper

- Donna Lay

- Eleonora Cort

- Eloise Marszalek

- Eric Blumberg

- Fiona Coll

- Florence McCambridge

- Gary Pilapil

- Heather Ryan

- Henrik de Gyor

- Ian Patrick

- ian smile

- Jack Holmes

- Jack McLeod

- Jacob A. Ratliff

- Jacqueline Fouche

- James Erwin

- Jason McAdoo

- Jay Liu

- Jenny Benevento

- Jessica Beringer

- Jessica Lovegood

- Jill Armitage

- Joey Pearlman

- John Jordan

- Laura Nash

- Luca De Bortoli

- Luis Salinas

- Lynnsey Schneider

- Mary Beth Baker

- Mary Fran Thompson

- Michelle Chin

- Pam Drouin

- Paolo Montevecchi

- Paul Wagner

- Pavithra Olety

- Sahar Naderi

- Sandra Lloyd

- Sandra Schweizer

- Sarah Lowe

- Stéphanie Walter

- Stephen Low

- Tina Bouallegue

- Veronica Fuentes

- Whitney Lacey

- Zuzana Zilkova