The Sensemaker’s Guide to Auditing

Think of a city that’s grown over time. Some neighborhoods were carefully planned. Others sprouted up organically. To improve this city, you need to understand its current state – not just by looking at maps, but by walking the streets yourself.

Whether you’re dealing with a sprawling website, a collection of legacy systems, or a maze of documentation, understanding what you have is the first step to making it better. Auditing is a critical skill in every sensemaker’s toolkit, and this article aims to show you why.

What is an Audit?

Auditing is the a review to assess quality, relevance, performance, and alignment with goals. This simple definition also contains the heuristics for any good audit.

- Quality: Assesses content on predetermined criteria

- Relevance: Assesses user needs, interests, and intentions

- Performance: Measured by established metrics

- Alignment: Supports broader objectives

Auditing provides a unique dual perspective, revealing the overall structure and patterns of your content ecosystem while also highlighting individual elements that require attention.

The auditing process forces us to examine things systematically rather than making assumptions based on limited views. This comprehensive examination often reveals surprising insights about content relationships, gaps, and redundancies that aren’t visible when looking at individual pieces in isolation.

Reasons to Audit

Audits are essential diagnostic tools that help you navigate complex technological and operational landscapes. They can provide clarity, uncover hidden challenges, and offer strategic insights when systems, processes, or organizational structures become intricate or opaque. When it comes down to it, there seems to be two main reasons people conduct an audit.

Reason 1: Organizing People Around Understanding

Audits aren’t just documentation – they’re conversation starters. They help teams build shared understanding of what exists and why. This means:

- Product teams see feature documentation gaps

- Marketing spots messaging inconsistencies

- Support identifies outdated help articles

- Leadership recognizes resource needs

When everyone sees the same picture, planning improvements becomes collaborative rather than competitive.

Reason 2: Scraping Off the Barnacles

Content, like ships, accumulates problems over time:

- Outdated information

- Broken links

- Inconsistent terminology

- Duplicate content

- Accessibility issues

- Performance problems

Regular audits can help spot and fix small issues before they become big ones.

Common Usecases for Auditing

The following scenarios highlight critical moments when a comprehensive audit becomes not just beneficial, but crucial:

When No One Has the Full Picture

An audit becomes crucial when system knowledge is fragmented, documentation is scattered, or processes are unclear. By systematically examining components, interactions, and dependencies, you can create a comprehensive map that reveals the true complexity of your systems and content landscape.

When Communication Creates Confusion

If teams use different terms for the same things, or content lives in multiple places with various names, an audit helps standardize language and locate single sources of truth. It creates a shared understanding that improves collaboration and reduces confusion.

When Content Management is Chaos

Before you can fix content problems, you need to understand them. An audit helps track down latest versions, identify content owners, establish standards, and reveal gaps in your knowledge base. It shows you where content is outdated, duplicated, or missing entirely.

When Support Teams Are Overwhelmed

If your support staff keeps answering the same questions or sending people to hard-to-find resources, an audit can uncover why. It helps identify missing documentation, improve content findability, and spot opportunities for better self-service options.

When Processes Lack Clarity

An audit helps document undefined team roles, standardize task management, and establish clear workflows. It reveals unnecessary steps, missing documentation, and opportunities to streamline operations.

When Planning Major Changes

Whether you’re redesigning systems, adding new components, or dealing with mergers and migrations, an audit provides crucial baseline understanding. It helps identify integration points, potential risks, and hidden dependencies before you make big moves.

Approaches to Auditing

There is no one right way to audit, and most wisdom of the crowd available is to be as specific to your own intention as possible when designing your auditing process. That said, there is some useful thinking out there we can learn from.

Donna Spencer, a leading information architecture practitioner, outlines three levels of content auditing in her brilliant How to Conduct a Content Audit:

- Full inventory: Document every content item and asset. A comprehensive audit captures every piece of content across all platforms, creating an exhaustive map of organizational assets. This approach provides the most complete picture, revealing content redundancies, gaps, and potential optimization opportunities across the entire content ecosystem.

- Partial inventory: Audit top levels or recent content. Focused audits can target high-priority or recently created content, offering a strategic sampling that provides insights without the resource-intensive process of a full inventory audit. This approach works well for organizations with limited time or resources seeking targeted content improvements.

- Content sample: Review representative examples. Sampling involves selecting representative content pieces to analyze broader trends and quality benchmarks. This lightweight approach provides quick insights into content performance, style consistency, and potential improvement areas without requiring a comprehensive review of every asset.

Audits are critical diagnostic tools that help understand, evaluate, and optimize information landscapes. By systematically examining something through different analytical lenses, you can uncover insights that drive strategic decision-making and improve overall effectiveness.

There are two types of auditing you might take on:

- Quantitative auditing: Provides a data-driven perspective, using objective metrics such as volume, traffic, engagement rates, and other performance indicators. This method transforms an evaluation into measurable insights, enabling evidence-based decisions about strategy, resource allocation, and optimization efforts.

- Qualitative auditing: Focuses on the nuanced, subjective aspects, examining elements like relevance, tone, accuracy, and user experience. This approach goes beyond mere numbers, diving deep into the contextual quality of content, assessing how well it meets user needs, aligns with brand voice, and supports organizational goals.

In many cases, successful audits merge both quantitative auditing and qualitative auditing, for example you might use a quantitative full inventory audit to identify a subset to conduct a qualitative content sample audit.

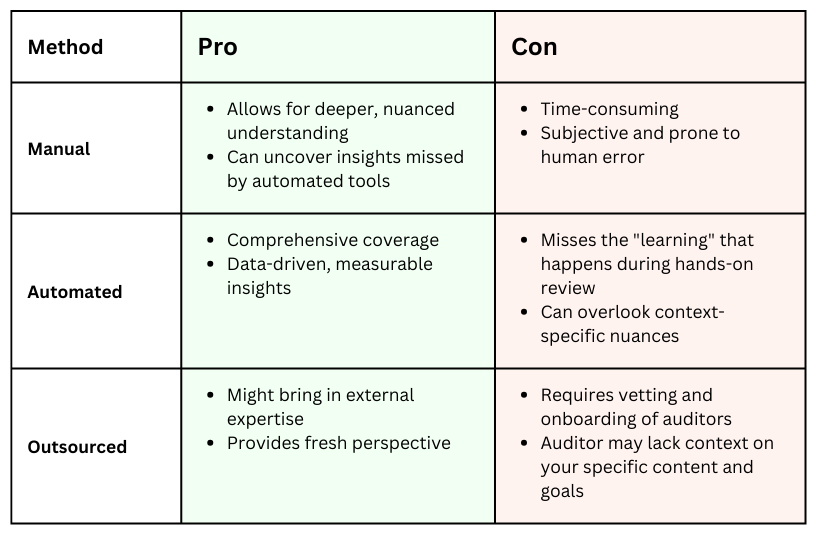

There is also an important consideration for who will be conducting or compiling the audit:

- Manual: Audited by hand by a human who has skin in the game

- Automated: Audited by a machine given a set of instructions

- Outsourced: Audited by human who has no skin in the game who has been given a set of instructions

Often a balance of all three of these types is actually what gets good auditing work done. While automated tools or outsourced resources impress with comprehensive lists, they miss the learning that happens during hands-on review.

Auditing your own content helps you understand it in ways that artifacts given to you can’t show. But using an automated crawler, or outsourcing to an analyst or data engineer to wrangle things into a spreadsheet for you can be a helpful first pass that should not be ignored for the efficiency it can provide.

Your unique intention changes how you might approach an audit. Let’s look at two examples.

Example 1: Your intention is an audit as a start to navigation or user flow redesign

In this case, please click on EVERY, SINGLE, (broken, badly labeled, low contrast, hidden in the footer, only like this this one page) LINK manually and note what you find as you go. The experience you have doing this will be invaluable to you in understanding what is there and how it all fits together (or gets weird) and outsourcing or automating getting the list will not provide anywhere close to that level of understanding.

Example 2: Your intention is an audit to assess the quality of thousands of articles

In a case like this, don’t click on every link. You will exhaust yourself and the process will deteriorate with your dwindling energy level. This is when having a list pulled for you is the best first step. Having a list of articles with metrics like traffic, time on page and bounce rate can give you a great sense of where and how to conduct a content sample audit for the express purpose of writing heuristics for how content should be assessed qualitatively by other people.

In a case like this I might recommend a sample of the best performing articles (high traffic, low bounce) and worst performing articles (high traffic, high bounce) to do a sample audit on. Once a list of 50-100 articles was audited by me, and heuristics documented, another person, or whole team could then be trained to confidently assess thousands of articles in a way that would be helpful and actionable.

Defining Your Approach

As you can see, the approach you use is deeply impacted by the intention you have, as well as the resources at your disposal.

When defining the approach you are taking, consider these elements:

- Why (intention)

- Where (scope)

- What (metadata)

- When (timeframe)

- How (approach)

- Who (resources)

Intention (Why)

When we understand why we’re doing an audit, we transform abstract requirements into meaningful actions. This isn’t just about checking boxes – it’s about uncovering gaps, finding patterns, and creating a foundation for improvement. What signals told us an audit was needed? What organizational pain points are we addressing? Getting clear on these questions shapes everything that follows.

Scope (Where)

In auditing, we need to be crystal clear about which territories we’re exploring and which we’re not. Are we looking at all financial processes or just accounts payable? Every department or specific units? The landing page accessible by navigation or all the pages on the server. This boundary-setting prevents scope creep and helps us go deep where it matters most. Mark these borders early and revisit them often.

Metadata (What)

The “what” of an audit is about keeping track of all our information pieces. Think of it like labels on storage boxes – we need to know exactly what’s inside each one. We do this through a consistent system of adding additional pieces of metadata that might be needed, like adding data like created by and date last edited, adding tracking numbers to each task, noting which rules and standards we’re checking against, and recording every “thing” we look at.

Timeframe (When)

There is an inherent rush to finish when auditing, because in fast moving information environments, it is common for an audit to be out of date before we are done. Timing in audits isn’t just about start and end dates. It’s about understanding cycles – fiscal years, reporting periods, review cycles. Map these against your audit activities. When do key stakeholders need findings? What’s the rhythm of the business you’re auditing? Align your timing with these natural cycles rather than fighting against them.

Approach (How)

Detail your methodology – sampling approaches, testing procedures, documentation standards. But don’t just list steps. Explain how these methods serve your purpose, and what they will actually take to get done. Think of future you. Is it really reasonable to look at hundreds of pages per day? Why these particular pages? How will you handle exceptions? What makes this approach right for this context? Make your thinking visible and if you can, get a gut check from someone else before you dive in. Once you have an approach determined, audit a small number (~5 to 10) of the intended things and then pause to audit your own auditing approach. Are you running into issues that at scale will create headaches later? Now is the time to address them before diving back in.

Resources (Who)

People make audits work. Map out your ecosystem of players – audit team members, subject matter experts, process owners, stakeholders. What unique perspective does each bring? What access or authority do they have? Understanding these human elements is as crucial as any technical aspect. Build in time for relationship development and knowledge transfer in your process.

Remember: Good audits are as much about making sense of information as they are about testing controls. Each of these elements should work together to create clarity from complexity.

Tips to Getting Started with an Audit

While the approach to auditing changes each time, I do have a basic, recommended path to share.

Step 1: Determine the intention and scope of your audit

Making sure not to bite off more than you can chew is the surest way to make this activity fruitful. There are far too many audits that die on the vine before any harvest can take place. Make sure to keep in mind your human scale when deciding how much to scope your audit to.

Step 2: Design your approach

Take into account the role of quantitative and qualitative data as well as access to automated and outsourced methods of helping.

- Are you doing a full, partial or content sample audit?

- What will be included qualitatively and quantitatively to support your intentions?

- Who will conduct which aspects of the audit – you, someone else or a machine?

Step 3: Create a format for capturing metadata and insights based on your intention

At this point some form of a spreadsheet or matrix is needed. Some people choose to use a tool like AirTable others rely on the simplicity of spreadsheets. There are even tools out there that offer features around managing a content inventory, which can then be used for an audit task.

The main objective is to define the fields and formats for the data you will be creating as part of your audit. Be kind to future you. Reconcile any issues that might make you have to normalize or clean data later on.

For example, a common format for an audit is a simple spreadsheet with columns like:

- Page title

- URL

- Page description

- Content owner

- Last updated date

- Last updated by

- Content type (article, product page, etc.)

- Status (keep, update, remove)

Next you’ll want to determine what qualitative and quantitative measures you will be using when assessing content for both health and quality:

Common examples of elements you might include are:

Quality:

- Is the information accurate and current?

- Does it follow your content standards?

- Is it accessible to all users?

- Does it meet user needs?

Relevance

- Is this still useful to people?

- Is this still referenced in search or via reciprocal links?

- What is the traffic to this content?

- Is there any form of rating to rely on?

Alignment

- Does the content still serve its purpose?

- Is the content up to date in terms of strategic direction?

- Is language aligned to current direction?

Performance:

- Are links working?

- Do images load?

- Is metadata complete?

When doing this, make sure you are defining how you will capture the data for each field in your review. If you start out spelling out “Yes” and resort to “Y” at some point, there will be data cleaning to do later. I highly recommend designing your audit template like you would any other content type, by defining the metadata, including the acceptable formatting for values in each field.

My best advice is to be humane with yourself in your planning. When it comes to your manual review time, stick only to capturing things you know you will use to make a decision or determination later on. It might seem like a good idea to capture ten elements for every page in your audit. Until you realize the time it will take you to actually follow through on to a high level of quality. Consider timing yourself doing a few and then see if the math fits into your real life.

Step 4: Gather your tools.

Sometimes the hardest part of an audit is getting access to everything you need. Make sure you do that before you dive into the audit itself.

You might need:

- Access to analytics or other data sources

- Spreadsheet software or some other input mechanism for audit findings

- Access to all relevant systems — remember that in many cases user role will change what you have access to

Step 5: Document findings:

- Note issues that need fixing

- Flag content for updates or removal

- Identify patterns and problems

- Mark opportunities for improvement

While the spreadsheet is the primary resulting documentation of an audit, most of the folks you will want to understand what you found are not going to look at your big spreadsheet. Instead — consider writing a one-pager about what you did and what you found. If your organization has a lunch-and-learn or other sharing-culture, audits can be incredible stories to start to pay down any knowledge debt that has accumulated.

Auditing Hot Takes

Like any other activity that looks “as easy as making a list”, auditing is fraught with gotchas to watch out for. In this section I want to focus on three specific aspects of auditing that I think can make it a less effective tool in a sensemaker’s toolkit.

Power & Politics

Content lives because someone wants it to. An audit is not an inventory, and the difference is judgement. Inventories don’t address territorial battles or political resistance. When we are conducting an audit, we are proverbially “finding where the bodies are buried” — and this is the number one reason that projects don’t make it through or past the audit.

👉Assure that the auditing intention is framed in a way that highlights value to a variety of stakeholders. If you don’t give stakeholders another story to believe in, the auditing story will always start as one of judgement and bad grades on their past performance. When we give folks another story, like reducing customer support call volume (thereby increasing their bonus), they are often quite happy to get out the shovels and show us where their teams buried the bodies.

Meaningless Metrics

Most audit processes stop at counting pages, documenting structure and metadata. To make audits meaningful, we need metrics that matter to making decisions: support ticket volume, conversion rate, traffic etc. When we make a list, we have to think of ways we want to compare those things to one another — otherwise when we are done, we have a list but not enough comparative insight to take action. Alphabetical is seldom an insight.

👉Make sure you are thinking about the data you will need to interrogate your audit before you dive in. I often find the start to an audit is like a scavenger hunt of all the data sources I might use, and resources I might lean on to patch together the list I want, that contains the qualities I need to compare and contrast.

Broken Governance

An audit is out of date the second you are done with it and, in any sizable system, parts of it are probably outdated by the time you feel done with it. When we conduct an audit in a vacuum for the benefit of a moment, we can end up losing out on an opportunity to bring governance into the conversation early and often. Rolling audits sound great until you ask who’s in charge. Most organizations lack the authority structures to make continuous review work.

👉Spread the accountability to as many functions as possible during the auditing process. By bringing in folks from throughout the organization around the auditing activity you can create the makings of a governance council that might actually be able to take on the collective work of continuous review and regular auditing cycles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where else can I learn about auditing for free?

Here are a few places I found that offer FREE advice on auditing outside a paywall that aren’t peddling a specific tool or service:

- Donna Spencer’s How to Conduct a Content Audit (includes video and spreadsheet template)

- https://www.nngroup.com/articles/content-audits/ (includes audit template)

- https://digital.gov/2023/09/12/a-conversation-about-content-audits/

How do I sell the idea of an audit to my manager or stakeholder?

Don’t talk about auditing. Talk about money.

Talk about reduced support costs because users can find what they need. Talk about increased conversions because content is clear and current. Talk about lower maintenance costs because you’re not managing duplicate or outdated content.

Share real numbers:

- How much time teams spend looking for information

- How many support tickets stem from unclear content

- How many hours are spent maintaining redundant pages

- What confusing content costs in lost sales

Then position the audit as an investment in fixing these expensive problems.

How long does an audit take?

That depends entirely on your scope. A focused audit of high-impact content might take a few weeks. A full inventory of a large site could take months. But here’s the real answer: it takes as long as you can afford to invest. Start small, focus on what matters most, and expand from there.

How do I present an audit?

I really like this advice to layer your insights from Ryan Johnson from GSA. He recommends a “bite, snack, meal” approach:

- Quick highlights for executives (bite)

- Key findings and recommendations for stakeholders (snack)

- Full data for teams doing the work (meal)

In terms of my advice, I say: focus on impact, not inventory. Show what problems you found and what solving them means for the business — even if that means NO ONE ever sees your immaculate spreadsheet.

How often should we audit our content?

During my research for this post, I found a statistic I don’t dare believe. It claimed that 33% of organizations conduct content audits twice yearly, while 24% opt for annual reviews. I don’t believe it because if it was true I think the internet would be better.

Luckily, it doesn’t matter that the math seems fake here, because frequency isn’t the right question.

Better questions are:

- What’s changing in your business?

- Where are users struggling?

- What content causes problems?

Audit when these answers change. Sometimes that’s yearly. Sometimes it’s quarterly. Sometimes it’s rolling review of different sections. The goal isn’t perfect timing. The goal is maintaining content that serves your users and supports your business.

The Path Forward

Auditing is more than making lists. It’s about understanding systems, uncovering truths, and ultimately about creating change. The best audit isn’t the most comprehensive one – it’s the one that leads to meaningful improvement. Start with understanding power structures, not just counting pages. Build alliances before building spreadsheets. Create governance systems that support continuous improvement, not just one-time cleanups.

Keep your first audit focused and achievable. Learn from the process. Use those insights to build better systems for the future. Because ultimately, the goal isn’t to have a perfect audit – it’s to have content that serves your users and supports your goals.

An audit is just the beginning of the story. Make it count.

—

If you want to learn more about my approach to auditing, consider purchasing my recorded workshop “Strategies for Effective Audits” — Note: this workshop video is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.