A World Made of Information

The following speech was delivered at the Future of UX Summit on November 5th 2014.

—

Not too far into the distant future, everything from our current existence that can be digitized will have been.

I find myself asking questions about what that will mean for real life.

One of my favorite nightmares to think on is: What does our world look like once the screens are gone but the information remains?

I worry about how fast things are progressing and how slow we humans are to change. I worry about the businesses that I spend my days helping. They have heard for ten years now that Web 2.0 is going to change everything, yet they still live in a world where understanding Web 1.0 is a daily struggle.

At some point soon, every traditional business model will have been tested to the ends of its strength, both psychologically and financially, to keep up with the wave of change that information has inflicted upon it. No one will have escaped. Not you. Not your children. Not even their children’s children.

Navigational models will have totally changed but people will still have nonsensical words for the latest shiny thing. There will be some “fancy-new-hotness” that does something that people have never designed a thing to do before. And all too suddenly, we won’t be able to live without it. Then they will redesign it, piss us off and leave us wondering why we ever loved it to begin with.

I can hope for our collective future that at some point information will be ubiquitously recognized as the glue that binds our digital and analog worlds together. I can imagine a world in which findable, accessible and useful information related to and in one’s immediate context will be seen by many as a basic human right.

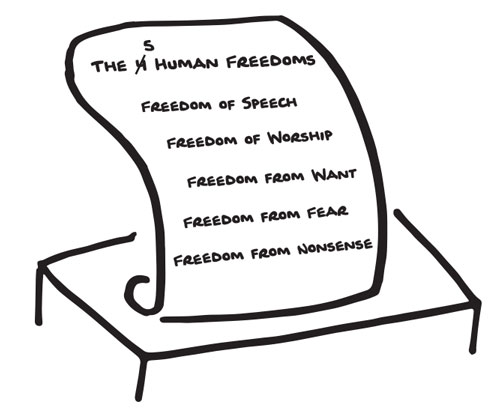

In 1941, in his State of the Union address, Franklin D Roosevelt outlined a taxonomy that has since been dubbed, the four freedoms. In the near future, I believe we will be forced to add a fifth:

Freedom from nonsense.

At some point, our expectations as users and receptors of information will have exceeded what we can even grasp at this messy moment living between an analog and digital way of life. The structures we have currently will eventually feel brittle to us, then they will feel unhelpful, only to rest in the place of feeling outdated. I know this to be true because this pattern has yet to fail us thus far.

New structures that make complex subjects and ecosystems more understandable will become necessary to combat all the disinformation, misinformation, too much or too little information that is created daily. We will need these new structures, not just to feel secure individually in all this information, but also to create social momentum around changes we need to make as a race in order to survive this messy world of our own making.

As we all know, analysis can cause paralysis. We are living in a world where it is already far too easy to feel overwhelmed and small in the face of this tsunami of information.

We could project our communal anxiety out a few years and settle into a rhythm of apathy and ignorance when it comes to information quality and stability. We could keep treating information like a fad born on the web in the nineteen nineties, and surely soon to pass. We could keep treating these information messes as if they are alien attacks from afar.

Or we could start admitting that we will need to slowly and methodically reinvent every single policy, process and tool across every community, language, industry and medium to deal with our new information-saturated reality.

To do this responsibly, we will need to expand the use and consideration set of an ever-changing set of concepts and principles called information architecture.

We will learn to cut through this messy minefield of change and consequence and pour understanding, clarity and agreement like concrete to be built upon.

Together we will create a truly new world. A world made of information.

Those of us interested in IA started preparing for this mission back when this new kind of a world was just a dream or nightmare that we all shared. But since then, a growing number of us have laid awake at night wondering when the call for our service would finally come.

We have spent years carefully architecting structures for the organizations who would let architectural thought in, and watching the structures of others fall down around them as a result of letting their architecture grow organically through the process of implementation.

We have struggled to keep up as an entire generation has grown up as much in digital places as physical ones, their expectations for structural resilience rising with every epoch-resetting release in the cult of Jobs.

Information architects already roam the earth helping even the farthest corners to create understanding across the mediums and messages currently being stored in silos of thought, politics and responsibility. Some of these natural-born sensemakers know the words for their super power, others are just now learning the words “information architecture.” Many more will learn soon enough.

If we are going to hold strong against the onslaught of information that is on a direct path towards each of the cognitive inboxes of our loved ones, we are going to have to get collectively better at this whole “information architecture” thing.

Five Lessons for Architecting a World Made of Information

The following are five lessons I am starting to teach to those seeking to practice information architecture across the messy physical and digital divide.

1. Reduce Linguistic Insecurity

When I was first starting out as a professional IA, I read an article on authority files and synonym rings on Boxes and Arrows. It was a great article. But daunting in its scope.

It took me three weeks to recover enough to explore controlled vocabularies after that. What I as a young IA took away from this task was the importance of providing documentation of a rigid language that computers needed to know in order to better serve people. To this day, each time I talk about controlled vocabularies with my peers, it feels like it is the least favored part of the IA process, and therefore one that is also easily overlooked, or undersold, especially on projects not involving a search or tagging system.

It is also a task I see be given to contractors offsite or extremely junior people to complete, in a vacuum. To be clear, I was one of those very junior people in a vacuum at one point.

And whilst making an endless spreadsheet of terms, I spent much of that time thinking “check the box, move on, this is for the bots, it doesn’t really matter to the users.” — Ugh, I know. Bad junior IA. But it just never seemed to click how it would impact users.

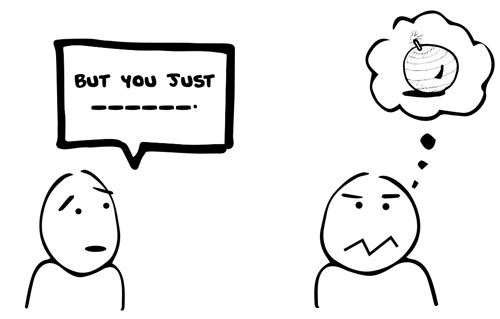

But my attitude about controlled vocabularies changed completely one day while in a client meeting. I was having an intense semantic argument with a client, like you do. We were going back and forth verbally about what something meant, enough that we had actually exhausted ourselves. You know that moment when the room starts spinning and nothing makes sense anymore… it was like that.

I realized in that moment that:

So much of what we do is captured not just in pictures, but in words.

And each word we choose is like a bomb of clarity or confusion about to go off in the brain of our collaborator. It occurred to me that perhaps we could control the vocabulary of our meetings the way I was taught to control the vocabulary of a system.

The client and I came up with the list of terms and decided who the owner of each one was. Then I went back and forth defining each term with each term owner. We landed on a definition we felt was tight. And then we held a workshop with everyone on the project, about 30 people, to review the list of defined terms. In the presentation we also introduced a list of now-defunct or outdated terms that we called the “Words we don’t say.”

As a large company with a low turn-over rate on employees and a history of over 40 years, they had plenty of semantic baggage. And this baggage was like a brick wall between the old and new generation of the company.

Our project was one of the first times the old school business folks and the new school technology folks at this company were collaborating, and we were collaborating on tools they would use themselves, as employees. So it made sense for us to be the ones to revisit the language.

Two amazing things happened after this meeting:

The first was that several employees of the old and new school pulled me aside to thank me for making them feel so much more comfortable. I was later introduced to a term called linguistic insecurity, which gives words to that anxiety-inducing moment when we feel like our language is not useful in our context. We all know that feeling. Well it turns out that discussion and documentation of language is the most effective way to reduce this amazingly pervasive ailment of our modern world.

The second thing that happened after the definition meeting was that we got in trouble for not involving the person in charge of the company’s controlled vocabulary. I found this to be odd because no one I worked with in that whole 30 person group knew that such documentation existed, they had never seen it, not even in training. When I asked why it wasn’t shared more widely with employees, the response was: Because it is really for the computers.

Richard Saul Wurman says that you can only understand something relative to something you already understand, so I find in teaching the power of controlled vocabularies to my students at SVA and Parsons, I am best off to start by make a distinction between two terms: lexicography and ontology.

Dictionaries are something we all understand, we are introduced to this concept quite young. Dictionaries are also something that few people wish to spend their time writing. Lexicography is the act of collecting and documenting meaning. Writing a dictionary is practicing lexicography.

Lexicography is what I was doing in creating my first controlled vocabularies, collecting and documenting meanings for words across many contexts. A dictionary doesn’t care if you have 200 words for snow or one. A dictionary doesn’t make those kinds of choices.

Ontology is choosing the meaning for our language in a specific context.

When Facebook choose the word “like” and “friend” ; When the makers of the first operating systems with GUIs choose to use the concept of a “desktop” with “folders” and “files” ; When Apple recently choose to not call their new product “iWatch” — they were practicing ontology.

People who make things and places choose language all the time.

And in this crowded market of ever-changing technology and trendiness, it is far too easy to not choose our language carefully or even worse we can feel like a language has been thrust upon us by a technology, medium or industry.

This leads to people choosing language that conflates, deflates, confuses or misrepresents the meaning for their work that was intended. Linguistic insecurity is rampant across every business, every industry, in every language.

It may even be a problem where you work.

So our first lesson for those wishing to architect in a world made of information is this: Know what you mean when you say what you say. Ontology is a group sport, focused on the clarification of meaning and the reduction of linguistic insecurity. It is a critical function for not just communicating with users, but also communicating internally and with partners.

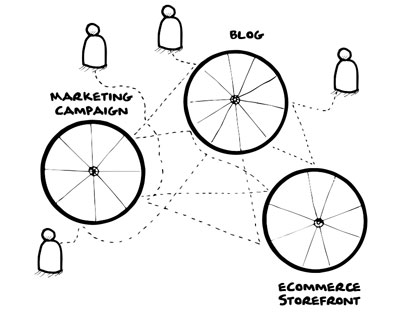

2. Map Ecosystems.

Our next lesson is about ecosystems. Yes, just like the ones you learned about in eighth grade life sciences class. For too long we have thought of the organizations we work in as the symbols that represent them, a set of boxes neatly nested within each other. But in reality most organizations are a messy human network of predispositions, preconceptions and prejudice.

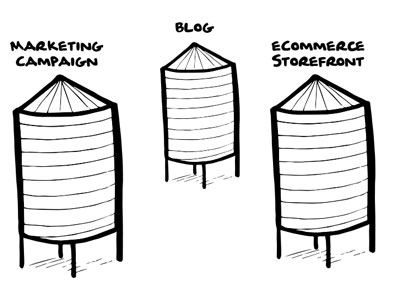

Silos. We all talk about these as if they are a metaphor. But they aren’t metaphoric at all, the silos in our organizations are as real as you and I are.

Silos are actual divisions of space, function, and responsibility. And we have spent a lot of time making taxonomies for these silos of place and thing, not realizing we were affecting ecosystems in the process.

There are two reasons things have “worked” in silos for this long:

- There were less places and things being managed overall

- Until fairly recently, places and things could be easily classified into two discrete buckets: Digital and Analog.

I don’t know about you, but the companies that I work for, suddenly have all these places and things to manage on top of their actual product or service.

Partner count is the new page count. And no one has pictures of these ecosystems.

They have an ERP system, and a CRM. They have several social media accounts, a help desk service, a 1-800 number, an eCommerce vendor, a WCMS, and a loyalty program. They have an intranet and an HR portal. They have a file share and a virtual private network. They have excel and some of them still have lotus notes. They have internet explorer 5. They have green screen interfaces used by hundreds of people sitting in cubicles. They have search landing pages.

And yes, they have a homepage. Most have several actually. And oh yea did I mention, that they also have most of those things in 5 languages.

Our users are starting to wander around, slip through the cracks in our systems, and get lost in between places they intended to go and we intended to receive them warmly.

It started back when we asked ourselves: “What would happen if people started to actually use the web on mobile devices?” Now we are in a time when social media and search have threatened the false sense of security provided by the much-adored home page. Mobile web usage may even surpass the use of desktop web usage by the end of this talk. We are finally approaching a time when saying the word “desktop” dates us as old school the way the word “dial-up” used to.

So with all these places and things made of all these various mediums, what can we learn from our history. When was the last time we had to deal with such things.

In the late nineteen sixties, during a time of social turbulence and economic change there was an obvious need to plan for the world in a new way, it was about this time that the term placemaking emerged.

This concept was based around a groundbreaking idea to design cities and towns that catered to people, not just to cars and shopping centers. This practice was focused on the importance of lively neighborhoods and inviting public spaces.

When I think about how to ensure an information future that is healthy for humanity, these same requirements emerge. We need to reconsider concepts as deep as the neighborhood. We need to assign meaning and rules to the new public spaces that are emerging.

Placemaking is the art of turning a space into a place by arranging it so people know what to do there. Urban Planners have been taught this concept for decades, and have used it to change spaces people move through into places where people dwell.

Information architects are now interested in discussing, teaching and practicing placemaking for this new world made of information. We are considering the lessons we can learn through the similarities and differences that virtual interfaces, way-finding and navigation systems have to their physical equivalents.

We are doing this because we firmly believe that these digital things that we have been making, are real places that people are dwelling.

The average American in 2014 spends 40+ hrs a month in places made of information.

That means that these places, that exist only online are the new third place for many people. So the ways that these places are made is starting to impact the ways that we live and communicate with each other.

I had the opportunity to talk to grade school children about my job recently. It was a career day type thing, where each speaker stayed in a classroom and did 20 minute rotations. So every 20 minutes I had a whole new set of users to test my language out on.

I did this exercise where I asked them all to help me to add a feature to the internet. “Anywhere on the internet..” I would assure them as they thought. Grade after grade, age after age, the similarity in their idea for what to add to the internet was astounding. The “Dislike” or “thumbs down” button. Like clockwork, one kid would bring it up, and the others would lose all control in a massive classroom sized explosion of laughter. Then they would all emphatically become obsessed with this idea.

Now think for a second about the impact on humanity if the thumbs down button was added? Then think about why the team at Facebook hasnt pursued it. Could it be because of a sense of cultural obligation?

My point in telling you this story is to remind you that digital stuff still has this feeling of “not real ness” for the young and for the inexperienced. Spaces where the rules of basic humanity don’t matter. Yet they are dwelling in these very real places and being affected behaviorally by what happens there. Much of which is controlled by people like us. By buttons and form elements. By business rules and content management systems.

We have an obligation to educate the next generation on the impact they stand to make through tiny decisions like the addition of a button. We also have the immediate obligation to make places that are good for humanity, as opposed to not. Meaning we have an obligation to discuss and critique what would and would not be good.

We are practicing the art of placemaking across digital and physical mediums for the first time in human history. We are finally questioning the assumption that a place has to be collocated physically. Artists and architects alike are becoming interested in whether a place or thing can exist only in the overlap of the digital and analog?

Projects like the 911 Memorial give us insight into what designing at the intersection of digital information and physical experience really looks like in the future.

Users are invited to explore a physical monument with a digital device that adds a much needed context and way-finding ability to a seemingly random arrangement of names and groupings.

This list is not alphabetical, and it isn’t arranged by company, tower or floor. It’s arranged by the relationships the deceased had with each other during their life as well as who they likely spent their final moments with.

This means, you simply cannot find a name on this physical wall without the assistance of a digital device. This decision is so different than one that would have been able to be made even a few years ago. We are starting to rest easy on the idea that these digital devices are with us for the long haul. We can rely on them in a way that we used to edge case them. We can use them to extend our real world. With this comfort, people are starting to challenge the status quo when it comes to patterns information has to adhere to in order to be understandable.

Projects like this challenge the idea that we have to stay in our silos, both as users and as makers. I look forward to a rich future of other examples of our digital and analog lives blending seamlessly.

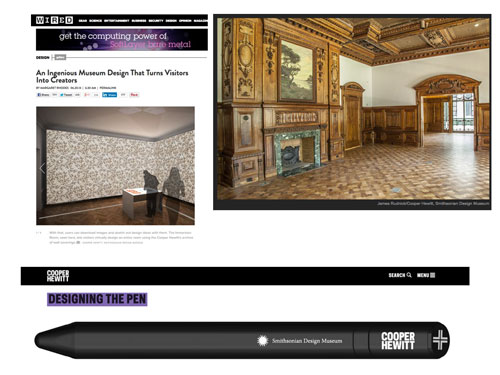

Last month, my SVA students and I were invited to run a hackathon to assist the team at the Cooper Hewitt to think through the ecosystem level impact of the addition of a brand new museum experiential device. Don’t get too excited, its a pen.

But this pen has an NFC reader, a RFID chip and a capacitive stylus. The “Pen” allows guests to collect and share exhibition information, as well as interact with the immersive museum environments. Like the wallpaper room, shown here.

While the “Pen” affords new opportunities for exploration services, the interactions with museum staff, and knowledge sharing across the Cooper Hewitt ecosystem is critical for the success of this experience.

As you can see from the room shot here, the Cooper Hewitt is in an old mansion, so the way that this very new feeling product will integrate into this place made of antiquity is a modern example of a challenge of placemaking.

One of the biggest considerations we had coming out of the hackathon was actually around the ramifications of moving from the default pattern of a residence which has many openings serving as both exit and entrance, towards a more museum-based pattern, of a single entrance and exit *preferably through the gift shop. The reason for all this talk about entrances and exits had to do with the proper choreography of having people end their session on and return their pens.

My point in sharing this story is to remind you that adding things to an ecosystem often affects other things in that ecosystem.

We may think we are just putting a layer on top of what is there, but each object we add, remove or change, impacts how users perceive and therefore use that place.

Our second lesson for those wishing to architect in a world made of information is: Understand the places you are making and the other places in the ecosystems those places exists within. Strengthen the connections between places and start to look for the literal silos that exist in your organization. Use the skills you have as a taxonomic cartographer to map the ecosystems that you affect with the places and things you maintain or are planning to create. Look for the spaces between places, the spaces users are starting to designate for use themselves. Like paths worn through a public park, these are clues to where our users want future places made. Paying attention to these opportunities is the only way to keep ahead of the wave of new channels and contexts being created daily.

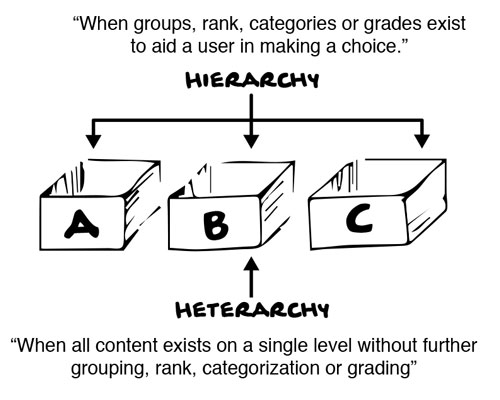

3. Strengthen Heterarchy

The home page is dead! Hierarchy is dead! All hail the hamburger menu! No. Wrong. Stop.

I hate to tell you all this, but hierarchy is unavoidable. Not just in IA, but in life. We humans really like grouping stuff. In fact, we don’t feel comfortable when everything is in one big undistinguishable bucket. This is not just the OCD among us, this is everyone.

Thats why we have arranged our whole world into a set of nested places. Thats why every room is within a building, street, neighborhood, city, region, country, and continent.

But the idea that hierarchy is dead has an interesting reality behind it. When it comes to digital technologies, our hierarchies are being used in new ways. Ways that would never have emerged in the physical world. Ways that make what are called heterarchies as important as the hierarchies that contain them.

To understand heterarchies, we can start with this: every hierarchy has a bottom. A set of things that exist on an equal level, without judgement, grade or further classification.

The deepest single-level branch of any hierarchy is called a heterarchy. And heterarchies are critical for us to understand as information architects in this new world of ours. Because an increasing amount of the world is actually contained in digital heterarchies. We don’t have to store physical things in physical boxes anymore. We are ok with unorganized digital systems because we don’t have to step over them or push them into a closet for house guests. But that doesn’t make them easy for us to use.

Heuristics have told us for years, across digital and physical media that we struggle to remember more than a few things on a list without further classification. The paradox of choice has warned us that these lists of unranked things is where we can become halted by anxiety of choosing how to proceed.

For a long time on the web, things were similar to the physical world. We could architect and rely on hierarchies to lead our users to a predictable and appropriate heterarchy of a manageable list of things. We could rely on a sequence that provided enough context as they traversed our structure guided by their choices.

But our world is no longer reliably experienced only from the top of the hierarchy down. Instead we must inspire comfort and understanding even when a user starts from the bowels of our taxonomic structures.

We are being asked to conduct business in a world where users can come into the storefront or office not just through the front door, but from what are equivalent to broom closets and back rooms.

On top of this change from top down to bottom up, we also have to deal with governance of our heterarchies. Search and social media have expanded the length of life for a url indefinitely, with every url being just one tweet away from making it into the Library of Congress.

What does this all mean for real businesses and organizations? It means our heterarchies are growing and will continue to grow. It means that the long tail is starting to show itself in the ghosted URL schemas we see cropping up to support these new bottom up experiences. It means that the barnacles are winning.

We are using heterarchies to preserve a once ephemeral history of campaigns and redesigns. We are starting to understand that as Karen McGrane recently said: “The web is not a laser printer.”

We are starting to see that digital places can be as hard to destroy or modify later as physical structures are.

Businesses across industries, technology or not, are starting to understand that the web is a lot less like a pile of marketing pages that don’t require printing costs than they thought.

We must start to talk about and strengthen the heterarchies in our world if we want to do this right. The information architectures of tomorrow might not fit nicely into a diagram of boxes and arrows, so we need to start to think about new tools and methods for planning these places, because even though they are complex to represent, they are increasingly critical to the ways users explore the digital world.

To architect in a world made of information, our third lesson is that we need to ask ourselves important questions about the scalability of both our hierarchies and our heterarchies, in the digital and physical places we make. For many organizations that means getting over the feeling like you can delete the web whenever you need to. For others that means scrapping off the barnacles that have developed over years of neglect.

4. Understand Transclusion.

For many years, we have been weaving content and links to create structures for people to use in understanding a context. But with technology advances like embed codes and APIs, we have seen the implementable resurgence of an important concept that is surprisingly as old as the concept of hypertext. That concept is transclusion.

Coined by Ted Nelson in the same work as hypertext, transclusion is the idea that content can be brought into and consumed in a place where it does not in fact live.

When I post this deck to a service like Slideshare, and then embed their player into my blog page, I am transcluding that content. I may also provide a hyperlink to the actual location on Slideshare where that content lives.

Transclusion is to block quotes as hypertext is to endnotes.

Both are important. We can use both in pursuit of our goal. One takes the user away to another place, one leaves them in the flow of the experience we are providing. It is our choice how we use these two tools to communicate our intent. It is also our choice if we enable our users to hyperlink to and/or transclude our content.

For years we have watched as social networks have started playing with transclusion of foreign social objects to keep people in their stream, Twitter’s transclusion of things like YouTube videos, but removal of transclusion in favor of hyperlinking Instagram posts shows the relative importance and competitive value of foreign social objects within the Twitter ecosystem.

Transclusion is the single concept allowing the mashup revolution to occur. It is one of the most important tools we can wield in an attention-based economy. The ability to transclude in today’s world, can equate to minutes on site vs. seconds; impressions vs. experiences; Places you visit vs. places you dwell.

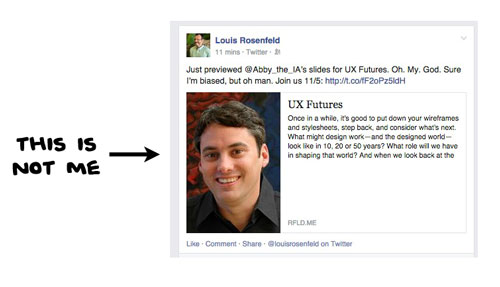

But Transclusion can be messy, as this post on Lou’s Facebook post shows brilliantly.

Our fourth lesson when architecting in a world made of information is to consider carefully the role of hypertexts and transclusion in the distribution of content. Think about your users potential desire to take your content with them. Make sure your content reacts well to being transcluded in networks users are likely to utilize.

5. Information is not content.

I get this queasy feeling every time someone uses the word information as an actual object. Anytime someone refers to it as something that could be picked, put down or thrown out. In fact if you were to put me on the spot right now and say: What is the most important lesson you have learned in your life so far, it would be this:

Information is not a thing. It’s subjective, not objective. It exists only in our heads.

Meaning we cannot share it or productize it, hard as we may try. We can take content in, and we perceive information but information cannot be handed to us directly. In other words, information is as uncontrollable as perception is.

Because information is whatever a user interprets from the arrangement or sequence of things they encounter.

For example, in this bakery case. There’s one plate overflowing with oatmeal raisin cookies and another plate with a single double-chocolate chip cookie. Would you bet me a cookie that there were never any more double-chocolate chip cookies on that plate? Most people would not take me up on this bet.

Why? Because everything they already know tells them that there were probably more cookies on that plate.

The belief or non-belief that other cookies were on that plate is the information each viewer interprets from the way the cookies were arranged.

When we rearrange the cookies with the intent to change how people interpret them, we’re architecting information. What would change in the minds of others if we evened out the plates? What would change if we only had one cookie on each plate? Maybe nothing, maybe everything.

I find that teaching this to my information architecture students is both liberating and terrifying. It invites them to think deeper but also to worry more. Never the less, I believe it to be the single most important lesson one can learn.

Without understanding how our intended users are likely to perceive what we make, we have little more than a pile of non-sense.

In this new world, we have to understand that data and content is not the same as information. Data is facts, observations, and questions about something. Content can be cookies, words, documents, images, videos, or whatever you’re arranging or sequencing. The information in this example is each individuals belief or non belief that other cookies were ever on that plate, as well as their subjective reasoning for the unequal amount of cookies.

One person might assume the chocolate cookies to be tastier or more popular. Another may smell the oatmeal raisin wafting in the air and realize those are fresher.

The difference between data, content, and information is tricky, but the important point is that the absence of content or data can be just as informing as the presence.

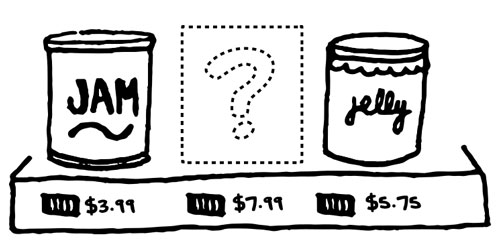

For example, if we ask three people why there is an empty spot on this grocery store shelf, each person would give us a potentially different answer.

The jars, the jam, the price tags, and the shelf are the content. The detailed observations each person makes about these things and their arrangement are data. What each person encountering that shelf believes to be true about the empty spot is the information.

So the fifth and final lesson from me to you today is to start to reduce the synonymous use of words like data, information and content wherever you work. I know, it will be hard.

I feel it is important to our explanation of things that we reserve the word information to describe that smushy, uncontrollable material our users make in their minds. I feel we must stop misleading our coworkers and clients into believing we can make information. With hopes that this opens up opportunities for us to understand the information that our content actually results in.

We must teach everyone we work with that we can create and arrange our content with the intent to communicate, but we can’t make information. Our users do that for us.

Before I go, I want to leave you with one final thought:

Just like in physical architectures, more information architecture is done by non information architects. We all dwell in structures, physical and digital, that were architected by indecision and pattern propagation. This reality not only worries me existentially but also practically.

We are fighting a force larger than any of us. We are wrangling a mess of our own making that has waged for as long as humanity.

It isn’t just big data. It is a world truly made of information. A world made of something so inherently subjective, a material so full of flaws. A medium that has such a tough time being molded and manipulated.

If we are going to do this right, we are all going to need to step up. Because information is a responsibility that we all share and a force we are all affected by.

Thanks for reading.

Slides are transcluded below 😉