Sensemaking Lessons

The following is a talk I delivered on October 28, 2020 at the Annual Federal Plain Language Summit. Video is on YouTube and deck is available on Slideshare

I imagined this overly bureaucratic agency with binder after binder of all the rules, edge cases and correct implementations of complex things. I imagined review committees and citation processing systems. I imagined a whole department of people whose job it was to see something, say something when it came to a sub par experience with something due to unmanaged complexity.

Complexity is you see, not a dark shadow. Complexity is the inner workings of beauty all around us. Complexity is the awe of sunrises, and the tide coming in and going out.

Complexity is not a choice but a condition. And we all live in that condition. Everything is complex. People are complex, and when there is ever more than one of us around, things are more complex.

Complexity seems to suffer from a sort of compound interest as you add people, each as complex as the last. The overwhelming level of complexity that can lead to, has a tendency to leak out in the form of frustration, mixed messages, and misunderstandings.

While we cannot escape this complexity, we can learn to manage or continue to suffer from mismanaging it.

The idea for a department of complexity has a few major flaws, which is how it landed in the dystopian side of my body of work around IA. To have a department of complexity, we would have to have achieved some pretty low probability prerequisites:

- Convinced ourselves we already have our arms wrapped around complexity enough to judge the fittingness of others’ approaches to managing it.

- Documented examples of good and bad complexity management in practice

- Published academically-based theories, frameworks and recommendations to reference to sense makers across all industries and fields of practice

And I know, as many of you know, how impossible all three of those things would be to achieve. I don’t even have to tell you how fast everything changes, how hard things are to document and how much harder still it is to actually reproduce the effect had by someone else when it is your thing, and your turn.

Complexity is wiley. It makes you think it can’t be controlled for fear that you will exert your systems thinking ability on it and have it lapping at your feet soon enough.

When Katherine invited me to come speak at this event, my head went back to the department of complexity. Because if ever there was a body of people in the American government trying to take back some control of complexity, it is the plain language community.

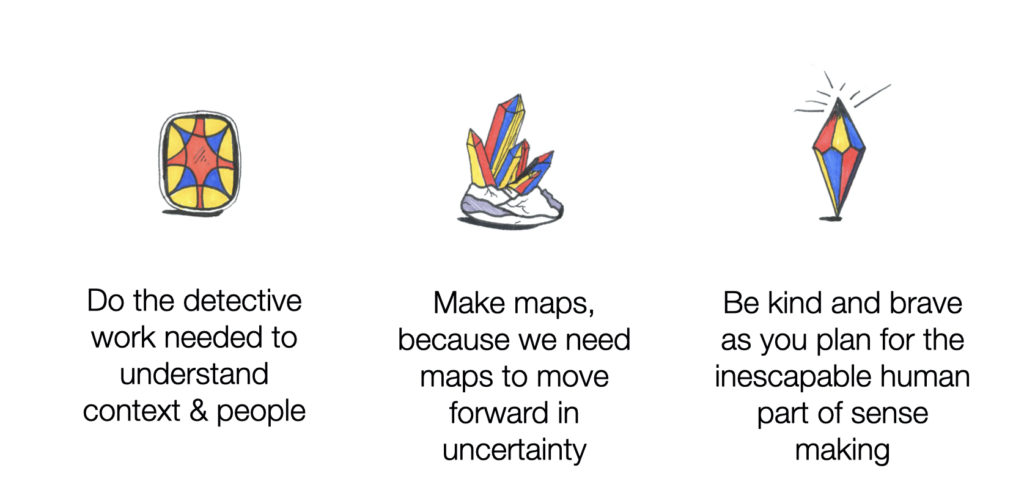

In this talk, I have unearthed three of my most prized gems from the dark complexity caverns of capitalism. Many of you here have spent some time in these caverns and will know some of what to expect, but for those who are new: welcome. Please keep your arms and legs inside the zoom call at all times.

1. Swoop up, Swoop down — Swoop round and round.

My 21 month old son is currently learning the complexity of spatial metaphors and direction taking. Over here, over there, up, down, over, under, around, through, in, out…it’s fascinating to watch as he tries to grasp the context of what people are trying to express to him.

He has this one book called Hooray for Birds, and every time we read this one part I think about how information moves in organizations and more specifically how I feel like I have to move at the beginning of projects in organizations in order to understand that information flow.

I had a student ask me recently if I am given “…everything you need at the start of a project?”. I couldn’t help but giggle.

First at the idea that she thought that might be anyone’s actual reality, second at the realization that I didn’t actually want to do a project where someone did hand everything to me. It turns out I like the detective work upfront. And even more so, now that I have given it more thought, I think the detective work is actually the key to sensemaking. I don’t think the results would be as good if my clients did hand me everything I needed.

Because we have to understand complexity in relation to the situation that we find ourselves in at the moment of sensemaking, and in my experience that breaks down into two specific and actionable areas of inquiry.

- Context

- People

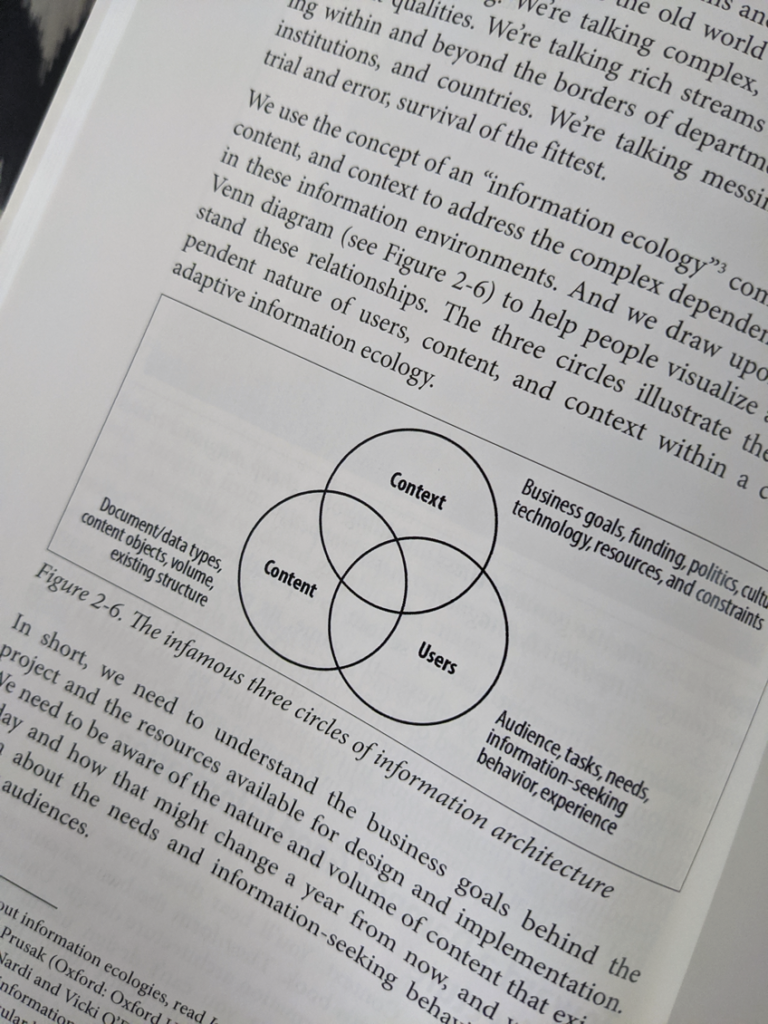

In the original Information Architecture for the World Wide Web, Peter Morville and Lou Rosenfeld provide a great framework for showing us how context and people have to be understood in order to create the right content or architectures to serve that content.

They establish clearly how important it is to understand the capabilities, aspirations and resources that make up the context of the assignment as well as the desires, needs and concerns of those that you seek to serve.

Context

I find at the beginning of a project I have to put on my headlamp and really go looking for details and clues of the context I will be working in. I find that every minute spent in understanding the context of the situation is one less minute I tend to spend in revisions later on.

I like to think about myself as a researcher in these moments, and I have a list of primary concerns I am generally checking against that I find helpful to make sure I don’t miss an angle.

- What is the historical context?

- What is the end user context?

- What is the internal user context?

- What is the systems’ context?

- What is the data context?

- What is product, market or industry context?

- What is the context of the time allotted, and team & resources given?

People

As we already talked about, where there are people, there is complexity — and sure enough as the sun rises and sets, the mess you are making sense of has people as a part of it.

I’ll be honest, the people part was a later stage level up for me and it took a lot of painful realizations to get there. I spent the first few years of my IA career trying to doggedly pursue what I saw as thoughtful, user-centered work. But back then I drew what I now understand to be too hard a line between a user and a colleague and I paid sorely for that misstep.

Mostly that came in the form of revision cycles, but also in the form of missed opportunities for partnership, and inefficient use of resources because I didn’t yet have a full enough understanding of the landscape of expectations and politics to be effective.

To truly be effective as a sensemaker I have to think more broadly about the people involved to make sure I uncover all the contextual clues.

Ask Yourself: Who are the people or teams:

- within what you are working on?

- below what you are working on?

- above what you are working on?

- adjacent to what you are working on?

- behind what you are working on?

Tool: Stakeholder Interviewing

The first and best tool I have to recommend in the pursuit of understanding context and people is Stakeholder Interviewing. Because I cannot even begin to express the amazing value that is often stuck in the heads of most teams. I find conversational research to be the most effective way for me to get a good sense of the context of a project as I start to explore it. By sitting down with people, especially one on one and interviewing them in a formalized way, I find that people are able to express themselves more freely and with more reflection and candor. I have consistently had people thank me for interviewing them, and often am told that people learned something in the interview. Which is always striking since I am quite strict with not adding anything other than questions to the flow of the conversation.

I think this works because people aren’t often given opportunities to speak freely as an expert in the mess in which they find themselves. They are instead often looked to to keep things moving, or keep up appearances. So whether they are new to the mess or thirty years in, giving them time and space to open up about their thoughts, historical experiences and insights allows for an often untapped resource to spring forth with the clear cold truth.

I have developed a fairly prescribed way to work through stakeholder interviews that I hope is helpful to share as you take on your next sensemaking assignment.

Set boundaries before the questions start.

I always have a script and as soon as the “Hi! How are you?”s are out of the way, I launch right into boundary-setting by saying “I have a script I will be using for this session, it goes into all the details that I expect you will want to know before I start, is it ok if I just jump into reading that?” — 99% of people say yep, and we proceed.

Next I lay out my script which is basically four points:

- You were chosen because your experience matters to the work I am trying to do

- I am recording so I can listen back and transcribe fully

- What you say in this room is private, and your identity will never be revealed to anyone

- I am interested in your experience, and your ideas — so there are no wrong answers

I end with asking if they have questions for me. Then I launch into my script.

Lean on the script, a perfect prop to push people further

I have received feedback from curious students about how interviewees feel about my use of an obvious and purposefully arranged script. I have also been goaded by many conversational researchers who believe that keeping the question flow loose is superior in method to keeping a strict order.

I have thought a lot about this and have landed on the following. I like to keep it loose in my actual facilitation, but maintain the control of my participant believing that the flow is precise.

I find that having the script there to ask a really hard question of a tough interviewee gives me a prop to push them a bit further. I can lean on the script as this third party in the room pushing us towards discomfort, even if we human-participants would prefer any easier, more casual path.

Plan a flow to build trust

Where I have landed over years of interviewing folks is that the order of the questions, does in fact matter. But not in that you have to always ask the same questions in the same order each interview. I believe that instead there are types of questions that have unique types of intentions, and I find that arranging those into a specific and prescribed order has allowed me to get the most out of my interviews.

I use the following question flow to build trust with the interviewee before getting into harder hitting subjects.

- Position: Questions that explore the stakeholders position in relation to the subject being explored in the interview.

- Beliefs: Questions that push to explore the things the stakeholder believes to be true as it relates to the subject being explored.

- Doubts: Questions that push the stakeholder to explore the things that make them less comfortable in the subject being explored.

- Color: Questions that you feel they are uniquely positioned to answer given their background, experience and/or answers to the above

I find that by grouping my questions into this framework of order, I am able to dive into complexity slowly with the people that I am interviewing and fully explore the depths, but only after the shallows are well covered.

I was recently interviewed by someone and the very first question they asked almost bowled me over with its boldness and complexity. I could tell they were proud to have asked the question, almost like something they couldn’t hold inside any longer. I know this feeling well, and used to interview this way, start with a zinger so they take you seriously and ratchet up from there. Thinking about question flow ahead of time from the perspective of building trust has helped me change the dynamic of these interactions significantly and ultimately get so much more insight out of them.

Ten years ago people left interviews with me exhausted and concerned about the complexity ahead. Now, I hear people say they feel a sense of relief, they feel seen and even that they are excited for what lies ahead. I give using this script framework most of the credit for that 180 spin.

Talk to the right people

When I first give the advice to people to interview stakeholders, the first set of questions (after we get through the initial shock of having to speak to other people) is around who to actually talk to. Which is really getting at the question: What does it mean to hold stake?

When I say stakeholder, too many people hear “client”, “customer”, “boss”, “manager”, “owner” yet if we break it down to its essence to be a stakeholder means to “have an interest or share in an undertaking”

By that broader definition, you can see how the list of stakeholders quickly grows past the initial list of people in charge of things.

When I worked on the IHOP menu system redesign, one of my most fascinating interviews was with the back of house staff at an IHOP in New Jersey. The manager there carefully explained to me the “inner architecture” of the menu, the one that customers struggled to grasp with the current implementation of the menu system.

By asking questions and listening to the responses as the clues that they were, I was able to more deeply understand the context of what I was working with.

Every context I find myself in is like a new planet whose atmosphere is totally foreign. By finding the right tour guides, I am able to get a lay of the land and learn what the locals eat, sleep and breath.

Specifically I look for the people who:

- Could change the course of your project mid stream

- Sign off on your work or the work of your partners

- Will help you make the thing you are making

- Market the thing you are making

- Measure the success of the thing you are making

- Maintain the thing you are making

- Translate/interpret/adapt the thing you are making

- Provide customer service on the thing you are making

I find that covering off on all these bullets is a hurdle to overcome in itself in many organizations. Specifically I find getting permission to talk to the do-ers to be hardest. You see, the word “stakeholder” often means “decider” in many organizations and the do-ers don’t get to make many decisions. As such I have in many cases had push back when asking to talk to people outside “decider” ranks.

My best advice to deal with this kind of hurdle is to illustrate for the deciders that there is a list of questions you do not expect to be able to get answers to by anyone but the “do-ers” — then make sure to clearly attach the need for those answers to your end goal.

I did on one occasion get asked to not call the interviews “Stakeholder Interviews” — for “political reasons”

Give as much after the interview as before and during

Another hurdle I hear about a lot is the sheer scale of a typical stakeholder interviewing effort, especially when it comes time to take and parse the notes.

To be honest, no one seems to like my advice on this point, because it is hard. I have been doing this kind of work for a long time and truly believe that the only way to get the value of these interviews is to give as much after the interview as before and during it.

In practical terms, that means a few hard truths:

You have to ACTUALLY listen to the recordings back. I know, you were JUST in that meeting. But here is the thing, you actually weren’t. I mean you were physically there but emotionally and cognitively your focus was not ACTUALLY on understanding the participant at that moment. It was more likely ACTUALLY on getting through the meeting and not embarrassing yourself. Did you hear things? Yes. Did you get the jist? Yes. Did you miss more than you heard the first time and will be blown away to find this should you actually listen to me on this…. again, yes.

Transcripts are NOT notes, outsourcing doesn’t work. DO NOT, I repeat DO NOT read transcripts and convince yourself you are hearing all the things that happened. The intonation of someone’s voice, their breath, the pause they took after a particular question… all of this is lost when you let someone else, or even worse, a machine type out your interviews. People have attempted to convince me for years that typing my own notes instead of buying transcripts is SUCH a waste of my time. I see it as the opposite. I see the tedium of my note-taking as an essential part of the exploration. My notes are like a map I am making myself to find my way back out when I’m done.

Unorganized, long-form notes and transcripts are useless when you get to analysis. Don’t make the mistake of taking your own notes only to lock them away in their own long form documents for each participant.

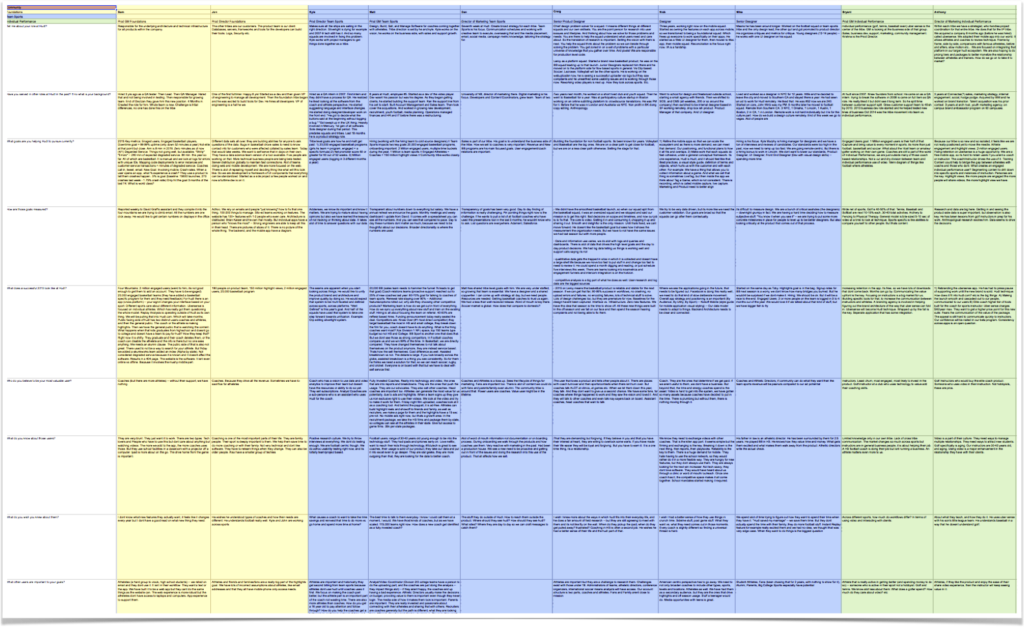

I find that setting up a spreadsheet where rows are questions and columns are interviewees helps me to look for common threads and/or contradictions across interviews — I also tend to arrange and color code the columns by role in larger projects where more than one person of each role is interviewed.

This makes it easy to see incidents of group-think or times where dynamics within a sub group are impacting the whole.

This is a screenshot of my organized notes from a round of 10 stakeholders, all told I took me 15 hours to conduct the interviews and prepare for analysis. I see too many similar scaled projects estimated at 5 hrs with the assumption that all prep is unneeded and that recordings/transcripts will serve as adequate in analysis.

That’s right folks, before I can even sit down to say what I heard in aggregate, I have already spent 15 hours just gathering what I can from the people involved and preparing for the sensemaking to begin. This investment of time comes as a shock to most people, until they themselves are given the chance to slow down and do this part correctly and humanely. They realize those extra hours pay dividends later on in the sense-making process.

If you are interested in using my stakeholder interviewing process, consider buying my Guide to Stakeholder Interviewing from my Etsy shop.

2. Unmapped complexity breeds fear

Now let’s say you did everything I just talked about, you talked to all the people who had stake and asked them about what makes them excited, scared, nervous. You know what’s been tried before and hasn’t worked. You know about the treacherous paths of the teams that came before. You know how big this mess is, how many people are scared of it and why.

Welcome to the middle of the beginning, perhaps the scariest of all parts of our journey. This is the part where I, as the sensemaker, must remember that it is in fact darkest before the dawn. And that while I might now hold knowledge of all the anxiety on the project, I also hold all the information I need to get people over the fear that is likely holding the team back.

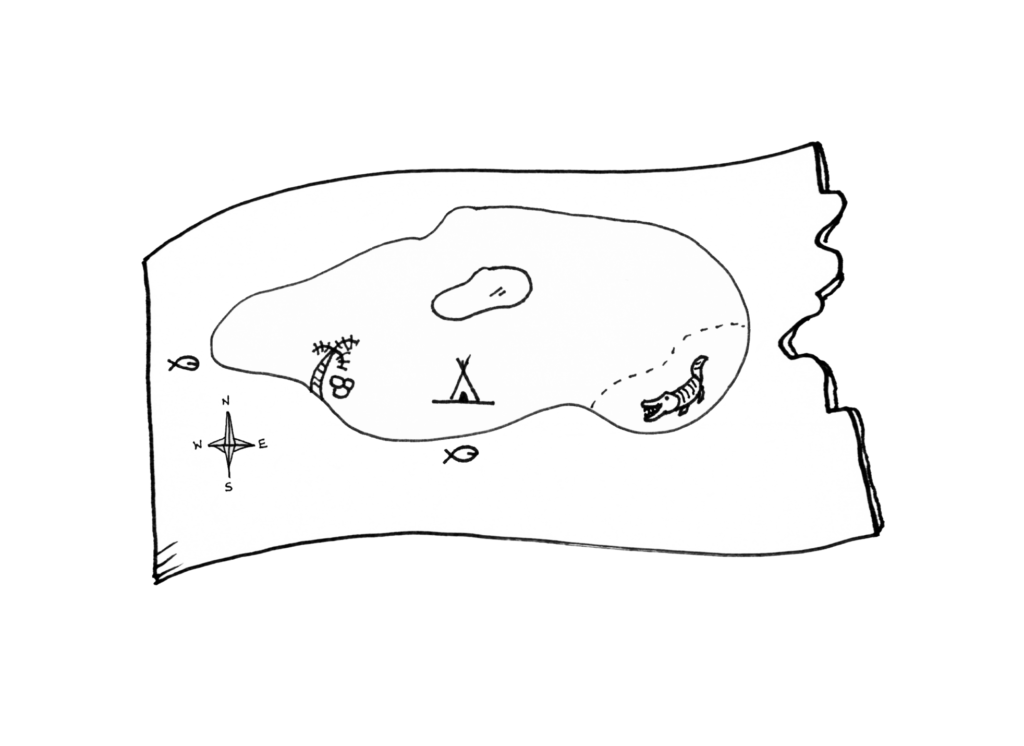

Imagine that you are stranded on a deserted island with your team. After weeks exploring the island individually and as a group, you start to build an understanding of how things work. Your team mates go off on their adventures throughout the day, looking for food and other additions of comfort that might be found and bring back tales of a lagoon of fresh water, a swamp with some not so nice gators, some amazing fishing spots and a grove of the most delicious pineapples.

How long would it take and how much information would you need before it felt like a map mike make sense? For most people, the answer is: Not long.

When we are faced with complex systems that we do not yet fully have fluency in yet, we need maps and guides to save us from the crippling fear of not knowing our own way. Organizations are the same as deserted islands in this way, we all are trying to find our way through to what is ahead.

I have spent too many hours in meetings and been on too many projects where people attempt to talk about complex things without any maps and guides for the team being asked to navigate this territory.

In my experience, the best projects, the ones that make the most of collective sensemaking power are less like a group of random travelers stuck somewhere, attempting to survive it and less like a group of information gatherers drawing a map of the complexity they collectively face and thrive in spite of it.

I have learned that over time, if no map is collectively made, the worst possible and most likely outcome is not that no map is made.

People need maps. The worst possible and most likely thing is that everyone will make their own map. And this is what happens in lots and lots of teams and organizations.

Robert Louis Stevenson once said “I am told there are people who do not care for maps, and I find it hard to believe” — as the author of treasure Island I don’t know whether I’m just another hammer seeing a nail or if in fact we are hitting on a human truth. It’s interesting how quick we are to admit to needing a map when faced with complexity in nature, yet think we can go it alone, mapless in digital territories of complexity without much concern – because gosh mapping would be just another hard thing we need to do.

The price we pay for that lack of investment is that in my experience, unmapped complexity breeds fear. I have seen time and again that the sheer task of mapping the complexity of exists so you can wrap a team’s collective minds around it is the single tallest hurdle for most sense makers to jump.

It is also the single piece of wisdom I find myself saying in talk after talk, mentoring call after mentoring call.

Do you have a map of what exists?

If not — make one.

If yes — proceed.

Basically at this point in the project, when the fear is high because so much complexity is trapped in people’s minds without a framework to hang it on, we need a map of what exists.

Sometimes what exists is a white space and a timeline to put something into it. Sometimes what exists is a whole system you are replacing wholesale, other times it’s a whole system you are changing a tiny fraction of. Regardless of what it is, you need to understand the shape of the problem that you are actually facing.

Tool: Auditing for Understanding

The tool that I find does the best job at releasing the pressure valve on mounting complexity is auditing. Now, I know this word is not the most glamorous. Let’s be real, the word Audit can create a lot of anxiety. But an audit is a reckoning, good or bad, right or wrong. Whatever is there, is there. I see too many people performing audits as a box checking or a technical task when creating a redirect schema. I seldom make it out of a Q&A session without someone asking me what tool could do the audit work for me. Similar to my advice on transcripts, these questions often allow me to have a very teachable moment about the danger of outsourcing understanding. So today I want to talk to you about the power of auditing for understanding. Because people need maps and to make maps, we have to survey the land and audit what we know about it.

I generally follow my stakeholder interviewing work with this kind of auditing work because I find that the two serve as critical inputs in my process of understanding people and context, but also at this point I am also starting to see the content that exists at those intersections as well.

When performing an audit we are focused on uncovering the shape of the problem. This part is often like an archaeological dig to discover what exists, what works and what is in the way.

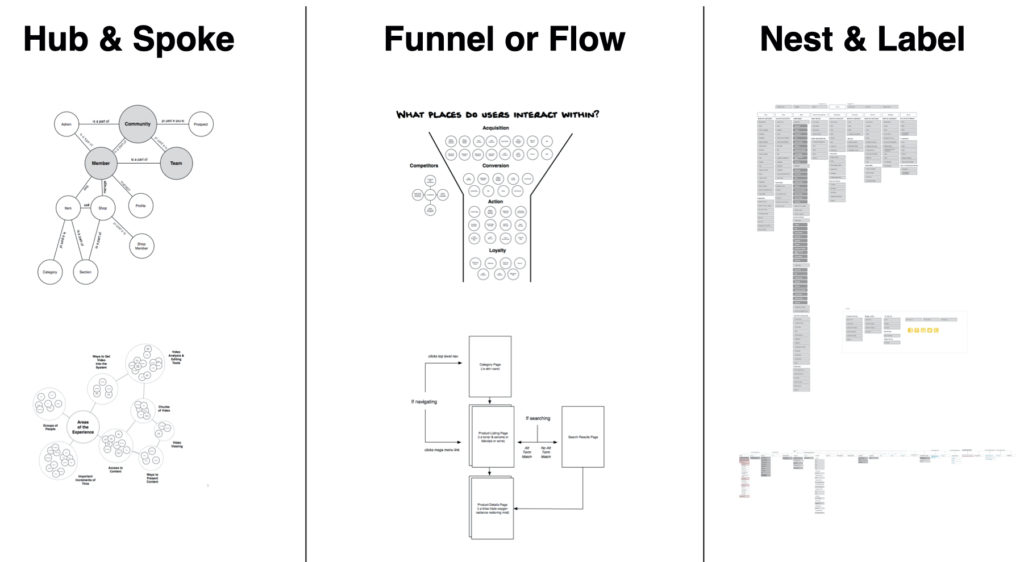

While the shape of each problem space is unique, I do find that there are patterns to the madness:

- Hub & Spoke: Where things are related to other things in connected in wild ways of heterarchy, hierarchy, association and sequence

- Funnel & Flow: Where things are related to one another primarily based on when or in what sequence they are encountered.

- Nest & Label: Where things are progressively disclosed and hidden when not needed behind labels meant to elicit wayfinding

I want to be clear, this is not meant as a this or that type model. Most of these shapes exist in most problem spaces. Each shape is unique as no two are the same. I once reverse engineered the sitemaps of two streaming video services to show my students how two similar seeming things at the UI level can be completely different shapes when zoomed out. One of the maps you see here is that of an ashram in India. I made it to save a group of thoughtful monks from arguing over the details of pages when really they struggled to understand any page in context to any other. Yes — it turns out that even the enlightened lose their cool without a map to guide them through the crashing waves of complexity.

While I have picked up little things in terms of diagrammatic technique that I enjoy and reuse, I do tend to reinvent the wheel every time I do a new audit.

At first I thought it was perhaps because I just haven’t found the right format, but as time has gone on and problems have come and gone, I now feel more like I need to reinvent the wheel every time because it’s part of the understanding process.

So with that in mind, the following is my best advice for diving into a systematic audit of whatever problem space you are sensemaking through.

Identify the bounds of the problem space

The first and hardest step when diving into an audit is to properly define the bounds of the problem space. You don’t want to focus too narrowly on just the part that you are actually working on, but getting the right circle drawn is an artful dance we must do at the start.

I find a framework called Circles of Control to be helpful in this task. I believe Stephen Covey coined this framework in the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People — and I find it to be the perfect way to think about drawing the boundaries on how I think about auditing.

I do however struggle to represent the right proportion for the circle of concern, so imagine a universe sized circle surrounding the other two.

Gather the right inputs

Once you know the bounds of the problem space, you have to gather the right inputs. Look at each thing on your list of things within the circle of control, start there and ask yourself: do I have what I need to proceed?

Do you have full access to:

- Functionality?

- Content?

- Data?

- Users?

- Stakeholders?

If yes: Proceed — but note I said FULL access. I have seen too many people attempt an audit without knowing they are actually looking at a subset of functionality. Seek out the super set.

If you don’t have full access, you must do the needed work to request it. I have found that often people just need permission to ask for what they need. In many organizations, would-be sensemakers sit on their hands far too long before they realize all they had to do was ask: for the meeting, the phone call, the email, the access privileges.

I have personally been amazed time and again what I can get done with my inbox and a professionally courteous and clear request for what I need, along with the right justification for why I need it.

Once you are through the things in your circle of control, move on to the circle of influence and concern. Based on your intention with the things in that circle, do you have everything you need?

Create a framework with the future use in mind

When conducting an audit, it’s important to think about the exercise itself as the journey AND the destination. I can tell you that the worst way to do an audit is the way 99% of people think to do one: sit down and look at the system and write down notes about what you like, don’t like, worry about, wonder about, and think would work better.

The reason this doesn’t work is that you have made the exercise entirely led by how you feel at the moment. Many people say “but I am an expert in making XYZ better, so my thoughts matter” to which I say, “I agree but while you might be an expert in making XYZ better, until you are an expert in the system you are reviewing your thoughts don’t matter as much as you exploring and seeing the product for what it is, not what you think you see at the moment.”

I find that the best audits I have done have relied on me setting the framework up before digging into the content. Each framework is designed to meet the needs of future me, first as I explore the problem space and then as I systematically map it out.

The most recent audit I did took me a month solid and I organized it into a spreadsheet. It was the audit of a complex transactional process that had over 3000 versions across all combinations of logic in english alone. I started by thinking about what I needed from this audit.

- I needed a searchable archive of what the team knew about each part of the process

- I needed a place I could capture data details along side user details

- I needed a way to capture what multiple users saw as a result of the same part of the process

That’s how I landed on a spreadsheet. I used rows to capture components and then added metadata to each row about how things worked and what I knew or didn’t know as a result of my audit.

Spreadsheets, while my official love language, are not always the right tool. I have found that in many cases a more graphic framework like a sitemap or association map can be more effective.

Create a humane plan of attack

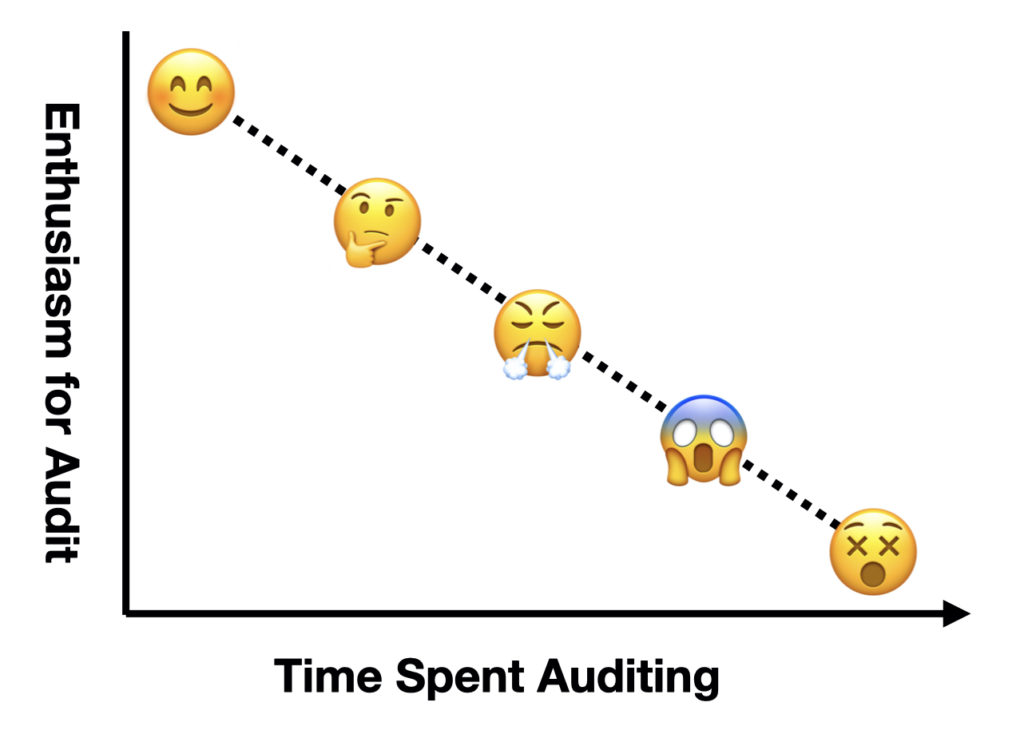

Once you set up the template, I will warn you — this is where the fun part can feel like its ending — unless you set yourself up for success with a humane plan of attack.

Here is what I see happen: people show up to the first day of the audit like it’s the first day of school. They have a new notebook, a fresh new pen and a strong sense of impending victory. By four hours in, they haven’t actually even decided how they are even doing the audit and the frustration starts to set in. They start to question the whole process all together, ultimately ending in a frustration-tantrum followed by an existential freakout in which they actually think:

“this is un-auditable” and consider how “within their circle of control” it would be to light a match to the whole darn thing and just walk away.

If that story sounds like you, I see you and I was you. I used to burn out during this exercise every time I took it on. But as the projects and messes got bigger, I was faced with the fact that I couldn’t just barrel through on sheer will and coffee anymore. So a few years ago, I started to manage my resources better in this activity.

Too often I see project plans with an audit activity and like weeks or even months to accomplish that task. If you are taking something like that on, do yourself a favor and make a humane plan of attack.

This usually looks like a schedule for most sensemakers. When I create my audit schedule I try to start from a place of how much ground can I cover before my frustration gets the better of me.

By breaking the larger audit task into smaller, easily accomplishable daily or weekly goals, you can give yourself something to work towards and set milestones to reach along the way that will feed your need for momentum and progress.

In the past I have broken audits up by user type, context, channel, task or component: whatever made the most sense to take on in chunks.

This might seem like a small thing, but by managing your own appetite for complexity you can look at a seemingly insurmountable task as just a really long list of smaller tasks with a schedule of how you will accomplish those tasks.

Assume best intentions of past sense makers

When conducting an audit, you are observing the relics of past sensemakers. I have found that coming to this exercise with respect for history and the slippery context of organizations has served me well.

I hear too many teams speaking ill of the problem without understanding the context in which the problem was created. In most every case I have observed in my professional career, if you dig hard enough you can almost always find a “good” reason for a past bad decision.

Whether the team was put into a corner, asked to put blinders on or just pushed to the edge of their own capabilities — there is always a “because reasons”.

Because we reorged

Because we ran out of money

Because we ran out of time

Because we had a contract to uphold

Because we changed our mind

Because users hated it

Because a competitor did it first

Because a competitor did it better

The list goes on and on and on…Regardless of the “because reasons” in your project’s history and lore, focus on finding and understanding those reasons.

By starting from a place of assuming best intentions you are more likely to be able to step into the shoes of those past sensemakers and bring the lessons of their journey forward so that your team has stronger grounding for the making sense of the mess ahead.

I find that audits that just point out what’s wrong, without providing the historical context of why are met with more defensiveness and less acceptance. We have to remember that auditing is often a judgement on the past work of others. We must be ready to take on this task with empathy if we want to find the truest story and not repeat the mistakes of past sensemakers unknowingly.

3. It’s people all the way down

That brings us logically to this last of the three lessons: it is indeed people all the way down. Try as I might to avoid the inherent complexity of the people part, I have not found a way around the idea that people are all over every mess we see or attempt to make sense of.

As people ourselves, we can make the mistake of barreling through the hardest parts of the sensemaking journey without processing the chaos for ourselves. But in my experience, this can manifest in its darkest moments as jade, apathy or worst of all when doing hard things: burn out.

Kindness & Bravery

Instead of a specific tool to recommend to face the people challenges that are inherent in every sensemaking journey, I want to offer a duality of ways to be instead.

I want to leave you with my best advice for how to balance kindness & bravery. Because I see these two skills pitted against one another in people’s minds far too often when really they can operate in harmonious companionship if you are gentle with them.

When NOT in doubt, ask a question

Sometimes when we don’t ask a question because we already know the answer, it ends up meaning we just know less of the answer. I find that if I am being both kind AND brave, I will ask the question even if I think I know the answer.

I often learn something new from the answer, even if it is indeed of the general flavor that I expect. Yet I see too many people not ask a question unless they are in doubt. This too often leaves us with our own mental models as our bounding box, which leads to the real problems going unnoticed or misunderstood.

Define & Defend Enough

When have you thought about this enough to have formed a solid point of view? When have you had enough of trying to convince someone to come around to that solid point of view? When have you experienced enough hardship that you know the current path is not the right one? When are you brave enough to admit it that change is needed? When are you kind enough to share your realization with those around you, regardless of if they see your actions as kind in the short term?

These are all the questions of the darkest hours on projects that are people all the way down. Balancing kindness and bravery in these moments relies on us spending time isolating and defining “enough” and then defending that definition with our own actions until our definition of enough is no longer serving us and we need to once again do the hard work of defining it so that we may defend it once again.

Working with other people relies on our ability to set and maintain boundaries. For our organizations, for our teams, and for our own sanity. Don’t make the mistake that too many sensemakers have made before you, don’t let the messes you make sense of get in the way of making sense of the messes of your own mind.

Pay it Forward

I truly believe that if you want to be a good sensemaker, you have to learn to pay forward the clarity that you reap from the sense that you make.

If you look at sensemaking as an act of service towards other people, recognizing the crushing weight of ambiguity and the life altering power of making sense, you will eventually start to see the amazing sensemaking system in which we all take part.

The secret to that system being that the feeling you get when your world makes sense, is only topped by the feeling you get when something in your world makes sense because you made sense of it.

Teach at least one person that lesson and your karmic debt for this lesson has officially been paid.

Be clarity for those drowning in ambiguity

As a sensemaker, I have learned how important it is to shine spotlights down dim alleyways that others are afraid of.

I have been the one who opens the spreadsheet of thousands of rows that no one thinks can be made readable and come back to the critics with an organized wellspring of information, now unlocked to do its best work.

I have been the one who reverse engineered a process flow diagram of a process so long and complex, with so many players, that it was described by many as impossible.

I have been the one to go down the rabbit holes that colleagues have warned contain untold disasters.

I have done these things because when I am being kind and brave, I remember that I can be clarity for those that are drowning in ambiguity.

I have spent the last decade and a half making sense of messes in private sector organizations large and small. I have worked on messes of a wide variety of contexts, industries, users and intentions. Yet I have not yet found one single deliverable, framework, method or tactic that works for every single mess. I have used posters in bathrooms to get the word out about mental model shifts we are after, used gym whistles to literally attempt to control vocabularies in meetings and instituted IA fire captains in an effort to provide the right governance structure for good IA to be done overtime.

Something that works today, inevitably won’t work tomorrow. Figuring out what works is indeed the hard part, and yet it is the part that if someone offered to do it for me, I would be suspicious: first of their ability to do it for me, and hand it back. Second of my ability to do my best work without walking down the path from not knowing to knowing.

I used to spend days dwelling in the uncertainty before getting the strength to recommend a path forward. Now I more often spend mere moments. When I see people drowning in ambiguity I reach out with a framework, an insight, a next step.

When I first started teaching, I used to get a lot of feedback from students that I answer with “It Depends” too often when being pressed to come up with things that “always work” — I once joked to another IA friend that I should have “It Depends” tattooed on my knuckles. I was once as an IA conference where “It Depends” was a BINGO square, and was rumored to also be a popular drinking game.

What I didn’t realize for far too long is that when I say “It Depends” — many people, especially those drowning in ambiguity hear something more like “There is no hope.”

The level of uncertainty that people experience when facing a mess is palpable and real. Saying “it depends” just reminds them how while the thing they are struggling with is indeed uncertain, so is the entire world so … yeah. No big deal, what’s hard.

When my book, How to Make Sense of Any Mess, came out in Japanese I eagerly looked at the cover image using google translate.

What I found was an even better knuckle tattoo I still havent had the courage to get inked. It said, “Goodbye Confusion”

And this serves as a much better mantra for me, although I fear that if I start answering IA questions with “Goodbye Confusion” then appreciate my yoda ways you might not.

After giving it much thought, I have come to this: if we are both brave and kind, then we will choose “goodbye confusion” over “it depends” everytime. We will choose to throw out the life raft of clarity to those drowning in ambiguity instead of continuing to describe the ambiguity and letting them drown in it.

There is an “i” in kind

Lastly I want to leave you with something I have learned all too recently. That is to be kind to yourself as you make sense of messes for other people, with other people, in service of other people.

I worry that there is a tendency to see being “kind” as having to come from a place of sacrificing oneself. What I have found instead is that to truly be kind, you have to show up as yourself even if that is hard and makes people uncomfortable in the moment.

Doing so will model for others that it is safe to do so. Doing so will allow perspective when the jade threatens to creep in and cloud your judgement. Remembering that there is an “i” in “kind” and turning that clarity inward when it’s needed to save yourself from drowning in your own ambiguity, is the only way to be brave and kind for others.

People might think that after all these years, and all these messes that I am no longer scared or that I am no longer in need of kindness. But that could not be further from the truth.

In reality, each mess I face feels bigger and scarier than the last. And each time I must face the monsters of my own mind, circle around the territory looking for people who can offer their collective wisdom so I might hunker down to make a map to quiet my human need for certainty in an uncertain world. It is only after the interviews and audits have worn a groove into my own mental model that I can be brave and kind enough to light the way for others.

I hope you are taking away from this talk permission.

Permission to do the hard detective work of understanding the current context and the people involved. Permission to ask hard questions kindly in pursuit of cold hard truth. Permission to make maps of the complexity ahead, because people need maps. Permission to plan for the people part, because it is indeed people all the way down.

As a concerned citizen, I truly hope these are useful lessons for you who are being such a source of clarity in a country I fear is currently drowning in ambiguity. I have tried my darnedest to teach you what I have learned in the private sector in an attempt to help. I know our worlds are not the same, and yet I hope these lessons will feel like just the right remedy for whatever lays ahead.

Thanks for helping to make this country a clearer place.