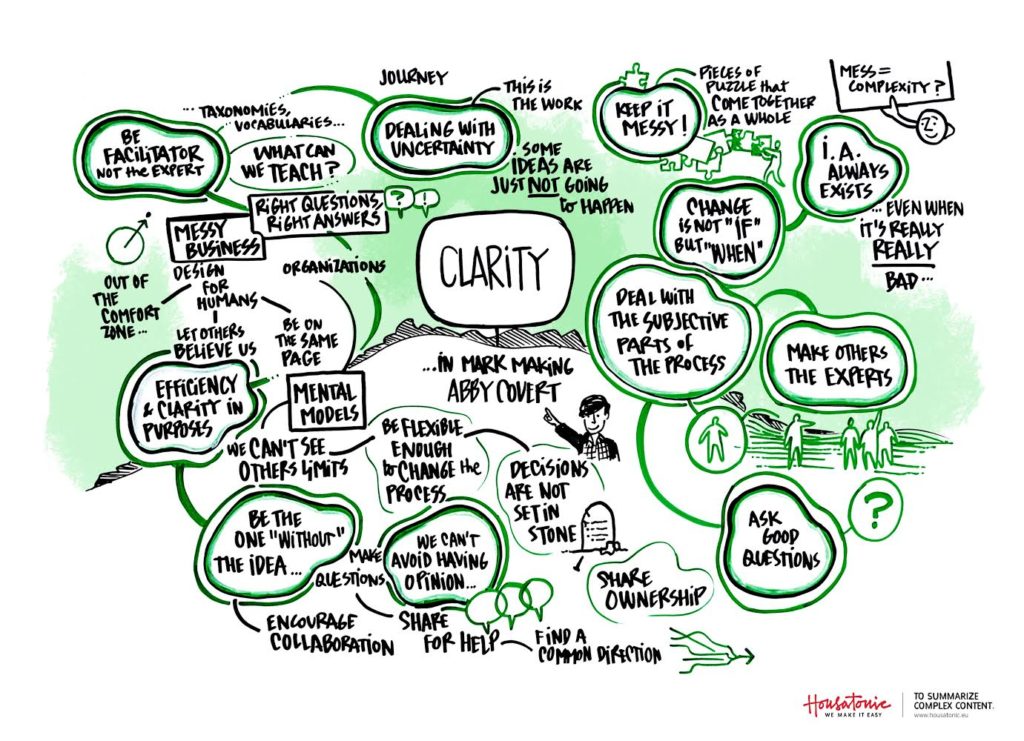

Clarity in Mark Making

The following is a transcript of a keynote given at the Italian IA Summit in Rome on November 12, 2016.

—

The theme of this year’s Italian IA Summit is “Leaving One’s Mark”

As I thought about how I could interpret this theme, I was brought back to my time in design school.

I was first introduced to the concept of information architecture as a graphic design student. In my earliest experience with IA, I was taught about the importance of establishing hierarchy of ideas and clarity of messages. At the same time as my graphic design and IA classes, I was also taking a variety of fine arts classes. One of the core terms I was introduced to during my studies was “mark making”.

Mark making as defined by the Tate is: the expressive qualities that add to the look and feel of an artwork

I got to thinking about how this concept of mark making could be interpreted under the lens of IA and what I found was a lot to consider about the subjective nature of the work we do.

In their seminal work, Information Architecture for the World Wide Web, Lou Rosenfeld and Peter Morville defined information architecture as both an art and a science. Since then, I have found as a practitioner that most of the wisdom that is spread about IA is focused more on the science side.

We talk a lot about how to look for evidence, form hypotheses, and test those hypotheses for effectiveness in a given context. We even gravitate towards vocabulary from science like taxonomy and test.

My question when faced with the concept of mark making was:

What can we teach about the art of IA?

In my personal experience as an information architect I have found that the science part, while good in theory can fall down in the face of the human part that none of us can escape.

We are designing for humans, as humans, with other humans. And that’s some messy business.

In the face of that mess, much of my work has been focused in teaching folks to deal with the subjective side of IA.

My hypothesis is that someone incredibly skilled solely in the science side of IA can end up massively dissatisfied because of a lack of softer skills like persuasion, politics and facilitation getting in the way of their ability to get good IA work done.

So today I want to talk to you about why those practicing IA should care about the subjective side of their work. I want to outline what I see as the factors that hinder mark making in IA and how we can be clearer in the marks we do make.

The most popular questions I get about doing IA work are not about the intricacies of crafting an effective taxonomy or about the nitty gritty details of documenting a controlled vocabulary.

Instead the most popular questions I get about IA work are what I classify as the “messy human questions”

- “How do I get executives to believe me about our users?”

- “How can I get the designers and developers on the same page?”

- “How can I deal with people in my organization who don’t want to change?”

- “How can a huge organization ever come to an agreement about what needs to change?”

There are a few patterns I have noticed that lead to questions like this that I want to start by sharing with you today.

Pattern #1: Mental Model Differences

One of the core skills we are taught to think about in IA is how to uncover and document the mental models of our users. We use tools like card sorting and task analysis to break a user’s view of the world into actionable tid-bits that make our work better for their use. But how often do we do the same for those within our organization?

I remember the exact moment that I was taught to apply mental model work to those I was working with. It was a chilly August morning in San Francisco at a workshop led by Dave Gray at UX Week 2010. I had been working on a project that had been keeping me up at night because of my lack of ability to get executives on my team to agree to the solutions I was proposing. I had done the research, tested the ideas and had a viable plan for how we could get it done with the resources we had. But each meeting with them, there was an unease that led to me frustratingly arguing for my way vs. their way.

In his workshop, Dave taught us to make an empathy map of what someone sees, hears, says and does and then to project what they might feel and think. This simple exercise broke the world for me. I realized that the research and delicate planning I had done meant nothing because it was too contrary to the mental model of the executives I was working with. On this project I had thought through the mental models of the users I was architecting for, but it wasn’t until I did the same for those on my team that I was able to make any headway.

Mental models are not preferences we have. They are the blinders we all walk around with. We literally can’t see any other way. It is incredibly hard to adjust our approach when we know that we have something that is just right for our users. But the reality is that to get good work done, we need the support of our organization and to get that kind of support we need to understand the mental models of those we are working with.

A good IA is able to balance the needs of users and the needs of the organization. It is incredibly common, however, to spend too much of our time pushing a 100% user centered approach that will just never work in the reality of an organization.

Pattern #2: Conflicting Incentive Models

One of the most surprising findings I have seen with organizations I work with is when the incentive model of those working there is in the way of the strategic direction a project is attempting to adopt. A great example of this is working with mid-size agile minded startups. In an environment like that people are incentivized to constantly deploy. Often this leads to a growing cruft of barnacles being added onto the information architecture of an organization. I am often hired by companies like this to analyze the cruft and show them places where their efficiency and clarity of purpose is being dulled by duplication or vagueness.

I can stand at the front of a room full of product managers, designers and technologists and get nothing but head nods and heck yeahs when I show them the aggregate result of all their on the fly decision making — but when they get back to their squads and face the reality of their next deployment, the likelihood of implementing change based on what I said is reduced by the way they are incentivized.

So along with the mental model of our co workers we have to think about how they are incentivized and how that impacts their ability to implement changes we might be suggesting. Often I find myself making the point that even if I could give an organization a shiny new cruftless IA, unless incentives change, the IA will eventually morph back to resemble what it is today.

Good IA is governed and maintained over time, not set once and forgotten. The way people in an organization are incentivized will deeply impact the over time part.

Pattern #3: Fear & Anxiety

We have all been there. When something in front of us is so big or so messy or so complex or just so out of our comfort zone that we just stare at it in avoidance. The problem with this avoidance is that with the addition of time, messes tend to get messier and complexities tend to complexify.

I teach my students that they have to be the ones that are unafraid. We have to be the ones who can walk into the darkest places and show light so others can make their way. But dealing with our own fear and anxiety is always the first step to being able to do that.

Sometimes people I meet describe a messy situation they are facing hoping I will pull out an easy button and tell them some secret that will cut their workload dramatically. Instead I remind them that as Robert Frost says “the best way out is through.”

Dealing with uncertainty is the work. Not knowing how it will all turn out is the work. The work is hard.

Good IA is done when we face our fears and the anxiety inherent in dealing with ambiguity and create clarity for ourselves and others.

Pattern #4: Time & Money

Everything we propose costs time and/or money to evaluate, to test, to iterate and to implement. What information architects can draw on paper or a whiteboard in a day may take months or years for an organization to actually implement. This pattern is probably the one we information architects have most in common with physical architecture. You can have the best idea for something in the world, but if the folks who are paying for it see it as an expense higher than they would like to pay — it is not going to happen.

I see time and money get in the way at every step, not just implementation. Sometimes folks don’t want to pay to even evaluate their options, opting instead to take whatever comes first to mind or maintains the status quo. Other times I see push back on paying to test a solution before moving forward with it. Some of the dumbest circumstances I have seen time and money get in the way is when the decision is made not to iterate after testing has been done. Instead they opt to build something everyone knows the flaws of. This is where the joke about ‘we’ll fix it in phase 2’ usually inserts itself.

In order to make our marks, we need to understand and work with the time and budget constraints that are put before us. Otherwise our ideas are never realized and our own time is wasted in the creation of throw away work no one will ever see.

Good IA work can be right sized to fit the needs of the circumstances. Beautiful structures can be built in the most humble of materials, the trick is to understand those humble needs as early in the process as possible.

How can IAs make clear(er) marks?

After being introduced to or reminded of these patterns, you might be thinking:

How can we ever make our mark in the face of all that?

…but I think this is where the art part of IA really comes in. Because you can’t throw the science parts at these messy human problems. So here is my advice for those looking to tackle the reality of IA work.

#1 Be the facilitator not the expert

Often when I am riding in a taxi or sitting in a cafe, someone will ask what I do for a living. I reply “I am an information architect” — and they are almost always struck with some kind of awe in what a fancy title that sounds like. “You must be really smart.” or “Oh, that sounds important” are all common replies I get back.

Now for years at the beginning of my career this kind of ego massage was the best thing that could happen to me in a given day. I was like “Why yes, it is important and I am a smartie” — but over the course of my career I have realized the danger in these responses, especially when it comes from within the organizations I work with. It is easy for the people I work with to look to me as an expert on things for which there is no set expertise. They think of my expert brain like a decision tree that can be logically climbed to reach the empirical right answer when in reality, all I can really rely on is my ability to facilitate them through a murky mess of decisions points that are unique to them.

When I was starting out as an IA, it was so uncomfortable to not know how to solve the problems I faced. And because of this discomfort, I would play expert inserting my opinions in a tone of certainty that put others at ease that I knew the way and all they had to do with agree with me. But as I have grown in my career, I have started to understand that saying “I don’t know but I can help you find the answer” is a much more productive stance to take.

One of the biggest questions I get from folks after workshops and talks about IA is “How can I get my organization to trust my expertise?” — and my advice is to not try to be an expert. Instead be a facilitator. Richard Saul Wurman once said:

we are on a journey from not knowing to knowing

Be the one that can help people walk down that rocky road.

#2 Keep it messy

As the author of a book called “How to Make Sense of Any Mess” people often assume I am incredibly neat all the time. But in reality I have found that I often need to help people get messier before we can start to make sense of what they have. There are nooks and crannies that they may have been afraid to explore that need consideration. There are mounds of considerations that they didn’t see the connection with to what they are working on. There are parts of their organization they didn’t think to include in the process. If I was to just start from the mess they showed me at first blush, I might actually be missing the piece of the puzzle that would make the solution we come up with hold together as a whole.

Over the years I have been through enough discovery phases to know that we often rush through the messy part to show our expertise in being able to tidy up. When in reality the best thing to do sometimes is to ask the questions that will make the mess bigger, to leave the whiteboard tangle unresolved for one more day or heaven forbid one more month.

We are all humans, we need time to unpack and rearrange things in our head. Sometimes when we rush this process, others will go along with us only to figure out much later that they didn’t have the right mindset or other perspectives considered to make a lasting change.

The most important advice I have for people in this area is to keep your work at the lowest fidelity as possible for as long as possible. When people see a messy pile of post it notes it invites more consideration and thoughtfulness then if they encounter a pristine diagram someone has spent time to perfect. So keep it messy for as long as you can stand it.

#3 Position IA as an ongoing conversation

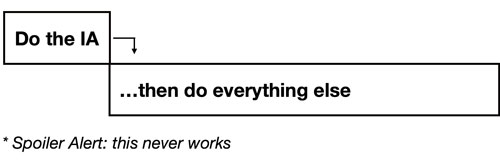

You have probably been a part of a project with a gantt chart that looks like this, with a spot towards the front (however brief) for “doing the IA”

While it is nice to see time given to IA at all in a project, I think that this way of thinking is incredibly flawed and leads to making our job harder over time. Because this supposes that you can set the IA once and forget it as you proceed with the rest of the project. I have never seen a project successfully completed this way.

This is where agile methodology and IA are actually a fantastic pairing in theory. Because in order to do good, thoughtful IA work, you need to consider it all the way through a project. As new information is revealed the IA must be flexible enough to change with the needs of the project.

Now this doesn’t mean that there aren’t steps that should be taken up front that result in a more well considered IA. Instead what I encourage is that IA is not introduced solely as a step at the beginning of the process. I like to talk about IA as an ongoing conversation that happens all the way through a project AND even more importantly as a conversation that extends past the life of the project because things can and will change as time passes.

The best word I can provide you with to get this point across is: Governance. In the same breath as teaching people about the importance of language and structure you must also remind them that language and structure are not without fluctuation. We must create a process for how to make changes to the linguistic and structural choices we make, otherwise we will quickly see barnacles start to grow and weigh down our original intention. It is not a question if we will need to make changes, but when.

I have a client right now who I am helping to establish a governance process. We have created a governing board which they have named the “semantic wizards” — each member of the team has been assigned to serve as an advisor to certain groups within the organization. It is their job to educate and disseminate structural and linguistic decisions in context to the work that their groups are taking on. But it is also their job to document the needs of their groups that require changes to what exist. They meet monthly for what they call “brain melting sessions” in which they participate in detailed semantic arguments about what exists vs. what teams are requesting.

It is their job to make sure everyone in the company cares about maintaining structural and linguistic integrity, but more importantly it is their job to make sure everyone understands that these decisions are ongoing not set in stone.

#4 See things from all sides

Have you ever dealt with a difficult person at work or found yourself in a heated argument? When this happens it is easy to label that person as a pain and move on trying to work in spite of them. It is also easy to feel the need to fight for what you believe. I often run into people in collaborative sessions that are so different in their understanding of the problems we are working through that it is upsetting or disruptive to the balance of the session.

When I was just starting out I spent most of my time arguing with people like this in front of other people, trying to logic my way out of the conflict. And I was actually pretty good at that. My father always said I would have made one heck of a lawyer. But all that ever did was leave me red in the face and without real collaborative progress on my project.

More recently I have started to try another tactic: neutrality. It is fact that we cannot avoid having opinions, however weak, about pretty much anything. While having them is a given, sharing an opinion is our choice. Often in the workplace, those opinions are about decisions to be made and therefore we see sharing our opinions as our democratic right.

But as an IA, I have stopped sharing my opinion as much as possible. Instead I like to help all sides present themselves so that a more democratic vote can occur. Often this means giving equal weight and hope to an opinion that is only held by two people as one held by a large group.

Politics is a fact of this job I have found over time that I cannot choose my way out of. Because of politics, often the worst idea actually has the most support and therefore is the most well presented and easiest to find agreeable. By paying attention to the lesser opinion, or the most contrary, I am often able to see the problem in a different light. In this new light, the problem gets just a bit clearer.

So my rule is now that I don’t share my opinion unless expressly asked. And even when expressly asked I will often find a way to spin my opinion into a question for the two (or more) conflicting ideas to be challenged by. It may sound callous but I have taken a great fondness for saying: “I don’t care” — this shocks people, but I remind them that it is not my job to be another opinion in the room. It is my job to weigh all our options and help them decide which way to proceed.

As IAs it is our job to be the coffee filter, not the grounds. When making a cup of coffee, the filter’s job is to get the grit out before a user drinks the coffee. What we remove is as important as what we add. It isn’t just the ideas that get the work done.

Be the one not bringing the ideas. Instead, be the filter that other people’s ideas go through to become drinkable:

Shed light on the messes that people see but don’t talk about.

Make sure everyone agrees on the intent behind the work you’re doing together.

Help people choose a direction and define goals to track your progress.

Evaluate and refine the language and structures you use to pursue those goals.

With those skills, you’ll always have people who want to work with you.

This isn’t an easy way to go about things, but I urge you to try it. I have found that where it is difficult it is also liberating.

#5 Share ownership

My last piece of advice for you is about letting go of the control I often see IAs hold on to with their work. Information architecture is incredibly hard to separate from other things like copywriting, content strategy, graphic design, interaction design and interface development. So why spend time trying to own it as separated from those things?

In truth the work IAs do on ontology, taxonomy and choreography when separated from those other things do not amount to much in the eyes of the users we seek to serve. While IA is the practice that defines these important parts, we as information architects cannot succeed if we try to maintain sole ownership of these parts. Instead we must share them with others across competencies. We must encourage collaboration on these parts as new information becomes available or as things change.

By proclaiming ownership of an information architecture we make it smaller and less important than it ought be. Language and structure are shared assets that we can’t avoid when making anything. Information architecture is an important practice focused on ensuring the resiliency of the language and structures we choose. When we try to own it, we are setting IA up to fail.

Instead we must seek to share IA with those we work with. We must teach others to consider the impact that language and structure has on their work. We must encourage everyone we work with to care about these things as much as we do. Only then can we make a clear mark on the world.

So in leaving you today, I hope I have gotten across the following. To leave a clear mark on this world, we must be ready to deal with the realities that come along with working with other people. We must think about how to apply the art side of IA which includes facilitation and dealing with the subjective parts of the process.

- Be the facilitator, not the expert

- Keep it messy for as long as you can stand it

- Position IA as an ongoing conversation, not a set it once and forget it exercise

- See things from all sides, and be ready to set aside your opinion

- Share ownership when it comes to important decisions about language and structure

The advice I have shared with you today is simple to state but a life long struggle to put into practice. My hope is that if you do put these simple ideas into practice, you will make a clearer mark on this world. Grazie.