The Sensemaker’s Guide to Stakeholders

If I had a nickel for every time someone told me their information architecture project failed because “the stakeholders just didn’t get it,” I’d have enough money to buy everyone reading this a coffee. Here’s the truth that nobody tells you when you’re learning about IA: the best structure in the world won’t survive contact with misaligned stakeholders.

Think about it. How many brilliant navigation systems have been destroyed by last-minute executive opinions? How many carefully crafted taxonomies have been mangled by committee thinking? How many elegant content models have crashed against the rocks of organizational politics?

The gap between a perfect IA solution and successful implementation isn’t technical – it’s human. And that’s why stakeholder management isn’t a nice-to-have skill; it’s the difference between your work living or dying.

So let’s talk about the part of IA that isn’t about boxes and arrows, but about the people who need to understand, support, and defend those boxes and arrows when it matters most.

This article covers:

Who is a Stakeholder in Sensemaking?

A stakeholder is someone who has a viable and legitimate interest in the work you’re doing. Sometimes we choose our stakeholders; other times, we don’t have that luxury. Either way, understanding our stakeholders is crucial to our success. When we work against each other, progress comes to a halt.

Stakeholder management in IA isn’t about manipulating people to get your way. It’s about creating shared understanding and momentum toward making sense of a mess together.

Reasons to Invest in Stakeholder Management

Let’s be honest – we love the satisfaction of a perfectly structured taxonomy, the elegant simplicity of intuitive navigation, and the quiet power of a well-crafted site map. Given the choice between sketching out another user flow diagram or sitting through a stakeholder meeting filled with competing opinions and office politics, many of us would choose the diagram every time.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: the most beautiful, logically sound information architecture in the world is completely worthless if it never gets implemented. And implementation doesn’t happen through diagrams – it happens through people.

The stakeholders who control budgets, influence decisions, create content, build systems, and ultimately determine whether your carefully crafted solutions ever see the light of day are the difference between theory and practice.

The most successful information architects understand that their job isn’t just to organize information – it’s to organize people around information. This means developing relationships with stakeholders isn’t just a necessary evil or administrative overhead – it’s the foundation that makes everything else possible.

Because:

- Language clarity depends on it – Without shared language with stakeholders, you’ll work twice as hard to communicate half as clearly.

- Structures need defenders – The best IA in the world can be bulldozed overnight by a stakeholder who doesn’t understand or believe in it.

- Messes are subjective – What looks like a well-oiled system to one person can be an absolute disaster to another. Understanding these perspectives is essential.

- Reality has many players – Stakeholders bring context you don’t have access to otherwise.

- Tension kills momentum – When stakeholders feel misunderstood or sidelined, resentment builds, and progress stalls. And while momentum stalls, messes grow larger and meaner.

Common Stakeholder Management Scenarios

Here are five common scenarios where stakeholder management makes or breaks your IA work:

- Disputes over what to call things – When legal, marketing, product, and engineering all have different names for the same concept.

- Lack of clarity on what things “are” – When everyone seems to be talking about the same thing but using different terms.

- Overlapping functionality – When teams unknowingly duplicate efforts or contradict each other’s work.

- Unclear priorities – When there’s no shared understanding of which audiences or goals matter most.

- Technical debt discussions – When addressing the pile of things that are issues with your technical setup as a result of prior decision-making.

Types of Stakeholders

Stakeholders come in many roles and power hierarchies, so in my Stakeholder Interviewing Guide, I outline the following list of types of stakeholders:

- People who could change the course of your project mid stream

- People signing off on your work

- People who will help you make the thing you are making

- People that sign off on the work of your partners

- People who will market the thing you are making

- People who will measure the success of the thing you are making

- People who will maintain the thing you are making

- People who will need to translate/interpret/adapt the thing you are making

- People who will provide customer service on the thing you are making

An important point to make here is: the org chart lies. The most important people for your project aren’t always the ones with fancy titles. Look for the “translators” who bridge departments, the folks everyone runs to with questions, and those quiet maintainers who actually keep things running. Power doesn’t always match influence. Find your real stakeholders by following the trust paths. And when in doubt, ask everyone you deem a stakeholder: Who might I talk to next? Their network and knowledge of who matters, matters.

8 Approaches to Stakeholder Management

When working with stakeholders in IA projects, there’s definitely no one-size-fits-all approach. Different situations and organizational cultures may require different styles of engagement. Here are eight stakeholder management styles worth considering:

The Coalition Builder

This approach focuses on identifying allies and building supportive networks before tackling resistance. Coalition builders spend significant time forming relationships with influential stakeholders who share their vision. They create a foundation of support that makes it harder for resistant stakeholders to block progress.

When to use it: In highly political environments where individual power is limited, or when attempting significant organizational change that requires broad support.

Example technique: Create a stakeholder map that identifies not just roles but relationships between stakeholders. Use this to identify potential allies and build a sequence of small wins that gradually expand your coalition.

The Educator

This style treats stakeholder management as primarily an educational opportunity. The focus is on increasing stakeholders’ literacy in information architecture concepts and principles, empowering them to become advocates for good IA within their own domains.

When to use it: When working with stakeholders who will be long-term collaborators, or in organizations where IA awareness is low.

Example technique: Create brief “IA Concept of the Week” materials that introduce one simple principle at a time. Use real examples from the organization to illustrate how the concept applies to their work.

The Strategist

Strategists align IA initiatives with business metrics and strategic goals that stakeholders already care about. They speak the language of business value first, IA principles second.

When to use it: When working with executive-level stakeholders or in organizations where financial or strategic drivers dominate decision-making.

Example technique: Frame IA improvements in terms of their impact on key business metrics like conversion rates, support costs, or employee productivity. Create before-and-after scenarios that demonstrate tangible ROI.

The Embedded Partner

This approach involves becoming temporarily “embedded” within stakeholder teams to experience their challenges firsthand. By working directly alongside stakeholders, the IA practitioner gains credibility and deeper contextual understanding.

When to use it: For complex projects spanning multiple departments or when stakeholder trust is initially low.

Example technique: Schedule “embed days” where you sit with different departments, observing their workflows and pain points before proposing solutions.

The Workshop Facilitator

Rather than conducting individual interviews, this style brings stakeholders together in structured workshop settings where they can collectively surface and resolve tensions through guided activities.

When to use it: When conflicts are primarily due to miscommunication rather than fundamental disagreements, or when time constraints make individual interviews impractical.

Example technique: Card sorting exercises with stakeholders to surface different mental models, followed by collaborative mapping to find common ground.

The Documentarian

This approach focuses on creating clear, accessible documentation that makes IA decisions and their rationales transparent to all stakeholders. The emphasis is on building an explicit shared understanding through comprehensive documentation.

When to use it: In regulated industries where decisions must be traceable, in organizations with high turnover, or with distributed teams.

Example technique: Maintain a decision log that captures not just what was decided, but why, including which stakeholders were consulted and what alternatives were considered.

The Agile Incrementalist

This style breaks down stakeholder engagement into small, iterative cycles, demonstrating value quickly and adjusting based on feedback.

When to use it: When stakeholder trust needs to be built gradually, or when the full scope of IA work is difficult to define upfront.

Example technique: Create “minimum viable taxonomies” that address one specific pain point, demonstrate their value, then expand scope based on success.

The Challenger

Some situations call for a more provocative approach that challenges stakeholders’ assumptions directly. Challengers use thought experiments, worst-case scenarios, and devil’s advocate positions to push stakeholders beyond their comfort zones.

When to use it: When stakeholders are stuck in “this is how we’ve always done it” thinking, or when potential risks are being overlooked.

Example technique: Create “anti-personas” or “dark pattern” examples that illustrate the consequences of poor IA decisions, making abstract risks more concrete.

The most effective stakeholder management often involves flexibly switching between these styles based on the specific stakeholders, organizational context, and project phase. The key is recognizing which approach is most likely to create momentum and alignment in your particular situation, rather than sticking rigidly to a single style.

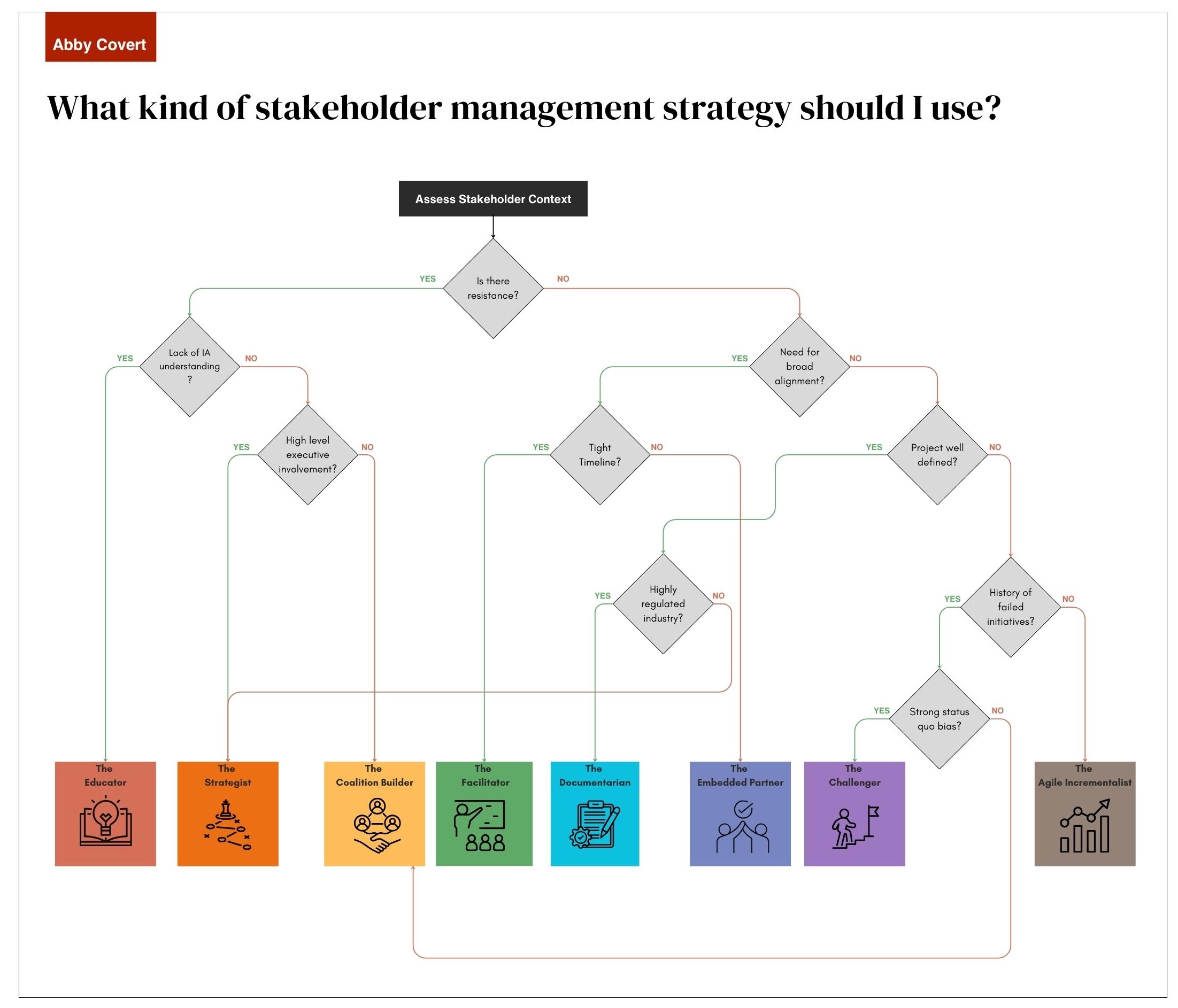

Choosing the Right Stakeholder Management Style: A Decision Guide

Selecting the most effective stakeholder management approach can make or break your information architecture project. Different organizational contexts and stakeholder dynamics call for different styles. Here’s a practical guide to help you determine which approach might work best in your specific situation.

See Full Size Decision Tree Here

Before choosing a stakeholder management style, ask yourself:

What’s the political landscape?

Competing interests among departments often create resistance to new information architecture initiatives, requiring careful navigation of organizational politics. Understanding who holds decision-making power and identifying potential allies will help you build the necessary support to overcome barriers.

What’s the IA literacy level?

Stakeholders with limited understanding of information architecture concepts may struggle to see the value in proposed solutions, leading to unnecessary pushback or unrealistic expectations. Assessing their knowledge gaps allows you to develop targeted educational approaches that build their confidence and ability to contribute meaningfully to IA discussions.

What’s your timeline?

Tight deadlines may force you to prioritize quick alignment over deep stakeholder engagement, shifting your focus to minimum viable solutions that can be implemented rapidly. Longer timelines offer opportunities for more collaborative approaches where stakeholders can be fully immersed in the process, resulting in stronger buy-in and more refined solutions.

What’s the organizational culture?

Documentation-heavy organizations often require formal presentations, detailed specifications, and sign-off processes at each project stage, extending timelines but creating clear accountability. Agile environments typically favor rapid prototyping, frequent iteration, and less formal stakeholder engagement methods, which can accelerate implementation but may create challenges in maintaining consistent stakeholder alignment.

What’s the history?

Stakeholders who have experienced failed IA initiatives in the past may approach new projects with skepticism and heightened scrutiny, requiring you to rebuild trust through early wins and transparent communication. Understanding this history helps you address specific concerns proactively and demonstrate how your approach differs from previous unsuccessful attempts.

Mixing Styles

Remember that these styles aren’t mutually exclusive. The most effective stakeholder managers adapt their approach as the project evolves:

For example, you might …

- Start with The Educator to build basic literacy

- Switch to The Coalition Builder to gather support

- Use The Workshop Facilitator at key decision points

- Employ The Documentarian to solidify decisions

You may also employ different styles with different groups …

- An Agile Incrementalist with the product team

- A Strategist with the leadership team

- A Coalition Builder with the design team

- An Embedded Partner with the data team

Contextual Factors to Consider

Your choice may also be influenced by:

- Organizational hierarchy – Flat organizations may respond better to collaborative styles like Workshop Facilitator

- Industry norms – Tech companies might embrace Agile Incrementalist while financial services might prefer Documentarian

- Project visibility – High-profile projects may require more Strategist elements

- Team distribution – Remote or global teams often need more structured documentation

- Your own strengths – Choose styles that leverage your natural abilities while stretching into new approaches

The flow chart above provides a structured way to think through these decisions, but always be ready to adjust your approach based on feedback and changing circumstances.

Tips for Getting Started with Stakeholder Management

- Design with, not for – Your stakeholders should be able to influence and react to your tools and methods. Get them involved early.

- Mind your language – Create a list of terms to explore with stakeholders. Define each simply. Document the history, alternatives, and myths associated with each.

- Don’t hide – Working on IA independently at your desk isn’t practicing information architecture. It’s hiding.

- Prepare for tension – Fear, anxiety, and linguistic insecurity get in the way of progress. To get through tension, understand stakeholders’ positions and perceptions.

- Document arguments – Create structural arguments that consider intent, information, content, facets, classification, curation, and trade-offs.

- Create measurement plans – Define specific goals with stakeholders that have intent, baseline, and progress elements. Use indicators to track movement.

Stakeholder Management Hot Takes

- It’s easy to reach agreement alone. Getting everyone to agree is hard but necessary work.

- The sum is greater than its parts. We need to understand many pieces together to make sense of what we have.

- Your language choices say a lot about you. How you classify and organize things reflects your intent but also your worldview, culture, and privilege.

- Be the filter, not the grounds. Sensemaking is like removing the grit from the ideas we’re trying to give to users. What we remove is as important as what we add.

- “Hey, nice IA!” said no one, ever. People don’t compliment information architecture unless it’s broken. If you practice IA for the glory, get ready to be disappointed.

Stakeholder Management Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How do I get buy-in for stakeholder interviewing? A: Make a clear case for collaboration. Position it as a knowledge transfer activity that will better allow you to navigate the project together.

Q: How do I talk about IA with stakeholders who don’t know what it is? A: Don’t say, “Let’s do some information architecture.” Instead say, “Wow, we have lots of information floating around about this, huh? I think I can help by bringing some structure to how we think about this.”

Q: What if stakeholders see the world differently than I do? A: That’s normal and expected. Your job is to uncover those differences and find a path forward that serves both stakeholders and users.

Q: How do I handle disagreements about classification? A: Create at least two structural arguments to compare options. Consider intent, information, content, facets, classification, curation, and trade-offs for each.

Q: How do I balance stakeholder needs with user needs? A: Your job is to uncover the differences between what stakeholders think users need and what users think they need for themselves. Bring data from both sides to the table.

The irony of information architecture is that its success depends as much on how you navigate the human landscape as how you structure information. In the end, even the most perfectly architected system can be derailed by a single stakeholder who wasn’t properly engaged, while a technically imperfect solution with strong stakeholder alignment often thrives.

I’ve spent years watching incredible IA work fail not because the labels were wrong or the navigation paths were flawed, but because the people side of the equation was treated as an afterthought. By contrast, I’ve seen modest structural improvements create outsized impact because stakeholders understood, believed in, and advocated for them.

Remember: information doesn’t exist without people to interpret it. The stakeholders who shape, maintain, and influence your work aren’t obstacles to work around – they’re the essential context that makes your work meaningful and sustainable.

So before you open another Figma file or create another sitemap, take a moment to map the human terrain. Your future self will thank you.

If you want to learn more about my approach to stakeholder management, consider purchasing my recorded workshop Tools for Stakeholder Management — Note: this workshop video is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.