Make More Sense

The following keynote was written for World Information Architecture Day Pittsburgh 2021. It was recorded in my home studio and I am quite proud of making some lemonade out of the lemons of being stuck at home by upping my production quality. The video and full transcript are provided below.

As an information architect who loves to make sense of messes, I have developed a lifetime curiosity about what it takes to make more sense.

What are the skills that allow us to make sense of the world around us? When do we learn these skills? Are we born as sensemakers and what parts of sensemaking might we purposefully strengthen over time? Is there an age when we set in our sensemaking ways? And are we ever too old to change how much sense we make?

Who wants to make more sense? We all do, right? Making more sense means that others understand us. And being understood, well that’s most often our goal.

Sensemaking is how we decide what things mean to us.

Sounds simple right?

Don’t be fooled by its simplicity. In truth sensemaking is so often harder than we allow it to seem, which leaves too many of us paralyzed by a should-storm.

I should be able to make sense of this. This should make sense to them. Things should make more sense by now.

In observing my two year old son making sense of the world, I have been reminded that the frustration brought on by the swirl of the shouldstorm comes before the making sense part is even possible.

One of his current favorite daily games is to unpack all of my meticulously arranged markers, pens, and pencils to create his own simple taxonomies or as he calls them “piles” – sometimes by color, but not always. The other day it was caps vs. no caps. After some time on the problem he proudly observed that “crayons no caps.”

I curiously observe him and wonder how he is making sense of the world through sorting, in ways he feels noticeably compelled and confident about now, when weeks ago all there was was wild hand movements and lots of throwing – seemingly no sense at all, just sporadic landings. Less piles and more scatters.

Now his piles have careful placements, arrangements, even most recently he has added verbal labels.

“These crayons, these markers, these pens….these Mama’s markers, these Jamie’s crayons…these red, these green.”

He is making metadata models in his head. He is finding new and different facets about the things he already understands. He is going deeper. He is making sense.

But before those metadata rich taxonomies, now obvious to him as the daylight, was the frustration of not being able to make sense of those same things. To look at them with a million simultaneous questions of what they are and what to do with them and what you are and how the world is and what it is to even be at all.

How could you possibly focus on making piles? You can’t find places for things until their meaning is clear.

I have watched his progress from letting fate drive his arrangements through throwing to making messy piles based on a momentary understanding to multifaceted labeling and categorization.

Once the hindsight kicked in, I understood each iteration he went through on his journey from the chaos of not knowing and to the confidence of knowing.

Now, I must admit watching him develop these basic sensemaking skills whilst destroying the calm of my marker taxonomies, was equal parts joy and frustration for me.

For the first few days, after Jamie developed this love of unpacking all my markers, I would carefully re-sort and arrange the markers, pens and pencils at the end of the day after his bedtime.

Y’all this is a nightmare. I became so frustrated every time his joy-filled face said “markers!”– knowing where he was headed and how much time it would suck from me later that evening.

I thought really hard about my frustration, and rather than dig in I thought instead about sensemaking. I thought about how I was quick to assign blame to Jamie’s being messy in the fog of frustration. But when I committed to make more sense, I identified my self-imposed pressure to maintain the markers in their “proper, correct, right” arrangements as being the primary source of my frustration, not my child who is just trying to take on the sensemaking journey of a multigenerational obsession with stationary supplies.

After much consideration, I decided that the minor uptick in findability and aesthetics that sorted markers provided was not worth the frustration brought on by my child’s unbridled joy for marker messes.

Finally I realized that if I didn’t actually care about the order that the markers were put away, he would do it for me — and even enjoy it if I made it part of the game. Putting things into things is his second favorite hobby, right after taking things out of things.

So now I live with unorganized markers but without the frustration of watching him ruin my arrangements because he wants to make sense of them a different way than I do.

I’m glad that I adapted, but more so I am glad that it made me curious about what happens when you aren’t a two year old and the frustration sets in? When your real life doesn’t line up with common sense, how do you make more sense? What is the set of skills that makes some people frustratingly unable to make sense and others to bravely make all the sense that is needed?

Our sensemaking must come to work extra hard on days where we have to weather a shouldstorm. Sensemaking is what we rely on when common sense is no longer enough or working as prescribed. Common sense is afterall, so often all wrapped in its own shouldstorm.

With sensemaking applied, “These markers should be neatly arranged because err….that’s pleasing to look at” becomes “We could put away the markers sloppy and quickly together since we know we will be back tomorrow to do this all over again” which makes more sense if we are optimizing for the joy over all other things. Which lucky for me and my life, we are.

I don’t think that sensemaking is just of interest to those of us raising humans, or to information architects. I think sensemaking is an undervalued, underutilized, under-cultivated skillset that most people and organizations would benefit greatly from.

Sensemaking is a skill set I think is widely applicable to any role where you are serving other people.

After more than a decade of people telling me that sensemaking is my superpower, and writing a book that boldly claims to know how to make sense of any mess — I decided to get curious and take a deeper look at my own experience of learning to make more sense and the lessons I learned along the way that made me the sensemaker that I am today.

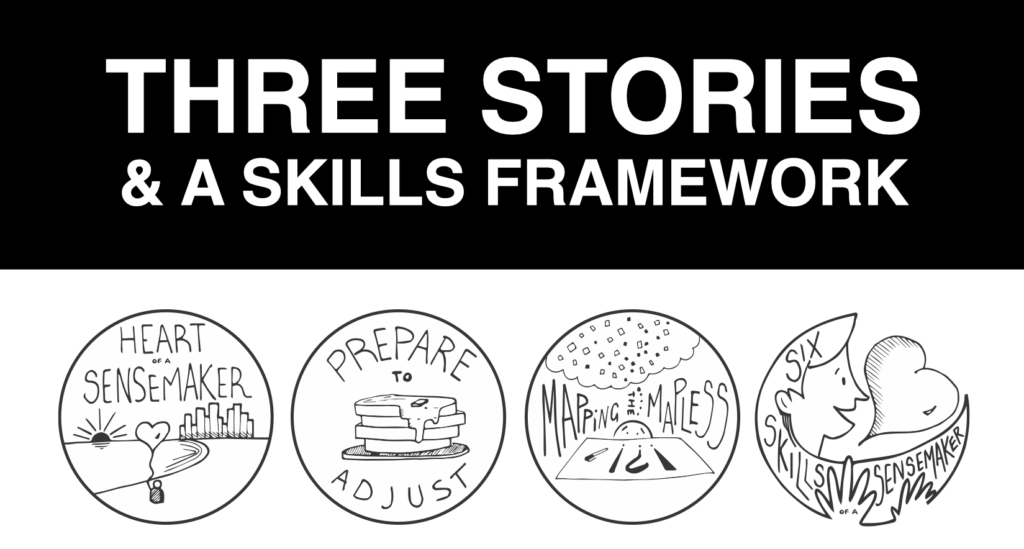

I want to tell you three stories from my own career and then leave you with a framework of six skills I think are essential to making more sense.

Heart of a Sensemaker

My first story is set in 2007 in Chicago, in a small healthcare agency where I was their IA team of one. My job was introducing information architecture to a group of people who had spent their careers in healthcare marketing doing award winning work without an IA ever involved.

To say there was an adjustment period would be an understatement. I found myself in almost daily disagreements with many of my co workers, who were often just defending the status quo of the healthcare industry, which was known for being immovable and overbearing — and that’s what you would say if you were being kind.

At this point in the story, I am 25 years old. I have been practicing information architecture professionally for a few years, and I know what I am talking about when it comes to the process to take on to support a variety of methodologies. I also know alot about the tools we could use and the ways in which deliverables are ideally executed and distributed. I even knew how to run a meeting with other adults where I didnt feel like puking and everyone felt like we got something done.

Here’s the thing, at this point in the story: I really only had half the equation. I knew how to make a place that had content in it that made sense to me. I even knew how to make a place that had content in it that made sense to users. What I failed to understand for several more years, is that that is only halfway there.

Let me give you an example.

One day, I was called into a meeting with a PM for a project I had shipped quite a number of weeks prior.

I was already busy with new work and was already annoyed that this meeting was occurring. They came into the room, also obviously annoyed to be discussing this “last minute request” from the client. It was a simple change, one that would not take “five minutes” — but it needed to be done immediately and it getting done was the linchpin to the whole approval process which had a payment milestone attached to it, that was already several weeks pushed due to other approval nightmares we could not have predicted.

They wanted me to replace a sentence that was quite crisp and clear to something much more verbose and vague. “To make the lawyers happy” they said. My blood boiled.

Ok… remember team, at this moment — This person and I are co workers. We are on the same team. I remind you of that because 38 year old me is still shocked by what is about to occur with 25 year old me.

Now I have a two year old, so let me describe this as I see it now. I had a meltdown straight to frustration town.

I was frustrated that this was overriding my recommendations, I was frustrated that I wasn’t being treated like an expert. I was frustrated that they had not fought harder for the user, feeling her lack of user centricity fell on my shoulders because I was the one tasked with bringing this new way of thinking and working to the agency.

I hardened my heart and refused to make the change. I demanded a phone call with the client in which we discussed the change and its “impact to user experience” — I didn’t win, and honestly I don’t even know how they smoothed over the event with the client. I eventually was called into a small conference room, we called the womb because it was used for “those kinds of chats’

My manager spoke as if trying to avoid a snake attack. They were brave and clear. I would make the change, and the next day we would sit down and talk about this incident, which they described as “a pattern.”

I made the change and sent it to the PM. Then I packed up and headed home to fret about probably getting fired the next day.

I didn’t get fired, instead I found a manager wanting to help me past the frustration to the making sense part. They told me that while my IA work was impeccable, I lacked some of the critical skills needed to work with other people.

Then they proposed that I go to a seminar called “Working Better with Others”

After getting over my ego and realizing it is 2007 and I have a job in a failing economy, I packed up for a few days and headed to this seminar.

On the first day, I came into a hushed room, everyone avoiding eye contact. Just take a moment to imagine the cast of characters at a seminar called “working better with others”

I sat down at the table with the easiest plop down. In the center of the table was a prompt for us to write. It was something about “why are you here?” — which in this context very much felt like “So, what are you in for?” — I wrote down briefly why I was there. “My co-workers say I am hard to collaborate with. They say I am aggressive and too demanding”

The moderator told us that before we started as a full class, they wanted us to introduce ourselves to the group and share our answers to the question. I went first, I have always been the brave one. Or pushy one, depending on how you look at it.

When I finished introducing myself, one of the people at my table said, wow I can’t even imagine YOU being demanding or aggressive. I turned to shoot daggers from my eyes and said “just shows you don’t know me very well, also be careful with books and covers.”

A great first impression, eh?

I didn’t learn all I needed to bridge this now obvious gap in those two days in the Chicago suburbs, but what I did learn probably culminated in a phone call I made to my mom from the parking lot at the end of day 1. Picture me ugly crying while pleading “why didn’t anyone tell me I was such an asshole?”

Her response was something like “You would not have listened if we had” and she was right.

This was the beginning of a long journey to learn that no amount of tools, processes and methods was going to strengthen my heart enough to ever really make sense with other people.

In order to make more sense, you have to be authentic as you facilitate others towards a result.

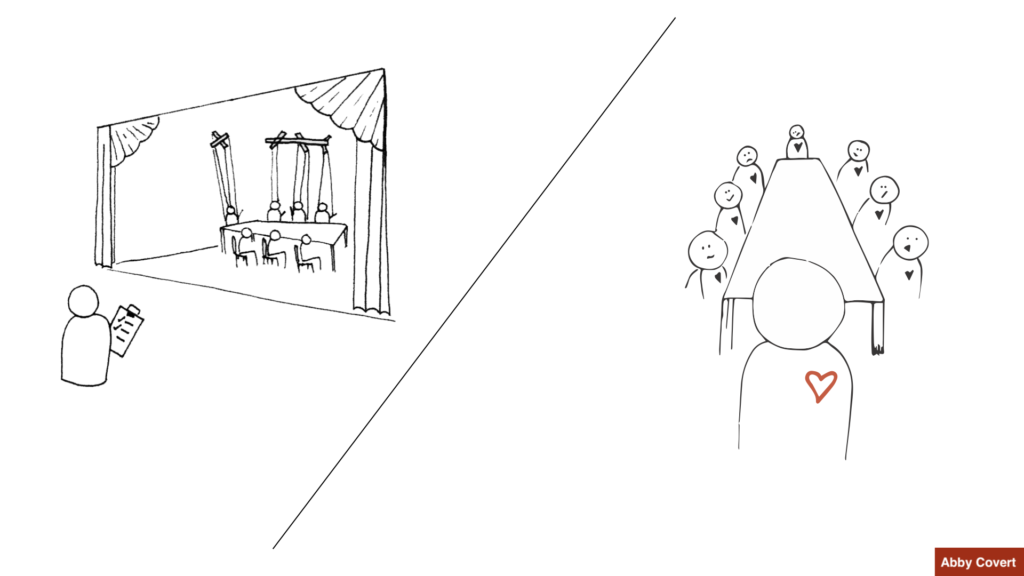

What I used to call facilitation back then was not so, more like design theater where I was the director and knew the acts which I would unveil over time to the audience, cast and crew. I was afraid to bring my full heart to those moments back then. My ego was too much in the driver’s seat telling me that experts always know the answer.

I have learned since that experts don’t always know the answer. True expertise is in being brave enough to proceed to find a way when one is not yet clear. True expertise is being able to say “I don’t know, but I have ideas of how to find out”

If my sensemaking had been stronger back then I would have seen the request they brought to me as a compromise that didn’t actually have a major impact on our intentions together — which were way more nuanced than just the “good user experience” of that single sentence.

I would have been able to move through the frustration part into the making sense part to see that this was not a call out of my lack of expertise or another battle lost. This was an adjustment that was needed for the wholeness of the intention to stay in balance.

Me refusing to make the change in favor of upholding the user experience of that single sentence wasn’t me being authentic, it was me being threatened and scared.

I don’t tell you this story because everyone has this same problem to work through. Not everyone is a baby asshole that would have acted like 25 year old me in this story. I tell you this story because I think that too many people never learn how to deal with the feeling part of sensemaking, which isn’t all roses and understanding. We can get stuck in the shouldstorm.

They should just listen to me, I’m an expert. They should care about the user more. I should be able to make them care about the user more. But here’s the truth as I have learned it, my list of shoulds is often really a list of fears and when I am authentic about that and the shouldstorm rolls in, I can work through the frustration part to get to the making sense part.

Sensemaking work is more than a knowledge of theory and methods. Much of the work I have found is on ourselves, admitting to what we do not know and cannot change.

Prepare to Adjust

The next story I want to share fast forwards a few years. I had recently moved to New York City to pursue independent consulting and one of my first projects was working with a team redesigning the information architecture of the IHOP menu system.

It also became the first time I had to turn to the power of process in order to proceed through the hardest parts of sensemaking work: uncertainty and ambiguity.

When you are the map maker, there is often no map to start from, or even worse, lots of maps that don’t make sense together.

And where there is no map or many maps in need of reconciliation, there is also often a collective anxiety and quietly building pressure to make a map everyone can agree on so we can get to work on whatever it is we are all here to do together.

I have learned time after time that you can take smart people who have a ton of experience doing what they do, put them together and not have the result of the group make any sense at all. They need a map of where they are headed or the anxiety will get in the way of making sense every time.

Contrary to what I think many believe, to be successful, a team facing this kind of mapless uncertainty has to focus on the process and not the result first. The result starts with making the map, but sometimes the thing we are after is too amorphis to proceed with the ways we have always done things. Sometimes the thing we are doing needs a new approach, a new method or a different timescale then we are used to.

A few years ago, I was engaged by an agency that had been hired to help Nike to build an internal tool to replace the myriad of disconnected tools that had been cobbled together over decades as they had moved their sales process online and into digital tools.

The promise of this digitally connected sales process was epic. All the data would flow through one system, connecting disparate processes that had never benefited from each other’s collective data wisdom before.

The presentation on the possibilities in front of this team was breathtaking. No literally, it would take your breath — first in excitement for the potential but then in scope of the promise. It was hard to imagine how this work would get done.

And like many projects, everyone was really good at what they do. The designers were ready to design, the engineers were ready to code, the client was ready to work towards progress. The requirements had been gathered. And yet there was something missing.

They needed to get from an amorphous blob of promises-made to a high-level process that could start to build momentum and understanding while the right set of frameworks emerged as the team needed them.

Thanks to the experience director on the business, Cindy Chastain and also the wonderful team at Nike who was able to go with the flow, I was given an opportunity to work through and iterate on the process day by day, week by week as we learned more about what was needed for the team to gain clarity and focus.

To be honest, at the time it was equally a breath of fresh air and palpable pressure for me to grow faster as a practitioner.

I started by interviewing the people involved and getting a broad overview of the system and the process we were trying to wrangle. It was a 96 week process that Nike used to get from the idea for a new product to that product being ordered by customers.

In that first set of meetings, I learned that while there was lots of documentation about the technical parts, and even the systems in place, there was no actual picture of the process we were seeking to support with this tool.

Everyone had their own process, they had been taking on with their own tools for years. The promise of combining these processes into one had been promised. And yet, at that point no one knew what they might actually look like.

Knowing how much a lack of shared map can impact a team’s focus, I took that as the call to make such a diagram.

Easier said than done. That diagram took me 9 months and 6 cross country trips to do right. We wrapped a room in Portland in craft paper and took every individual function through a collaborative mapping exercise where we plotted the steps they would expect to individually take in this process.

We did the process with one role, then cleared the walls and did it with another. After each interview I would plot them onto a digital map where I could start to lay them over one another, looking for contradictions and connections. I worked with a subset of Nike team members to revise and revise and revise the map until all the contradictions were resolved and the ideal connections between people and data sources was established and documented.

Once we had a clear map emerging, we started to look for other areas where a lack of understanding would get in the way. We decided that language was a big one, and started work on a controlled vocabulary for the agency team and the Nike team to communicate more consistently across roles.

We also identified that the agency and other external tech partners would need more user context to understand the Nike roles we were designing and building for. So we reformulated my interview findings from earlier in the process and turned them into personas that partners could reference when looking at the map.

With the map, controlled vocabulary and personas as working parts of the team culture, the designers and I got to work on what the system’s interface might actually need to be like in order to support the process and data needs that we now more fully understood.

We ran a series of workshops with the potential end users where we drew out scenarios that we picked off the map to zoom into and work on. We did a representative set of these and used them as scenarios to create a vision storyboard that helped to guide the client through what to expect ahead in the wireframe and interaction design review process.

Once we had the broad vision, the next challenge was that we had to prioritize.

I had started my undergraduate degree planning to work in print design — so this was a departure from my current digital centric work but a really interesting intersection with a skillset from days past. I was curious if the same IA process would apply to physical menus that did to digital ones?

We set out to redesign the menu using a simple process we developed for the team to go through. We ate a lot of pancakes, watched a lot of people order and eat pancakes and talked to alot of people about eating, ordering and selling pancakes.

We learned that the brand had shortened their name to IHOP, which was the popular acronym for the International House of Pancake. Since the name change then they had suffered a bit of a loss of identity. They also had grown the menu to an untenable length and added too many non-breakfast items that really were clouding the customer’s understanding of what IHOP stood for.

At the time, they were also officially waging a war on breakfast against other up and comers in the fast food and casual dining space finally catching on to the breakfast all day trend.

And as a special last straw to break their taxonomy, new regulations had been added to require that restaurants of a certain scale disclose their nutrition information on their menus. But adding this information to the already crowded 16 page glossy, syrup sticky pile was overwhelming to say the least.

They needed to get agreement across the organization on the items to remove from the menu. Then they needed to redesign the menu with these new requirements.

We got to work and in research identified a few major flaws to be fixed.

At this moment in time, new customers often asked the waitstaff what to order at IHOP — which seems silly in a place that is known for pancakes. But as we watched people use the menu and decide what to have we noticed something important. There were pancakes on every page. Yet because of that, there was nowhere to see ALL the pancakes. In an effort to up the pancake-yness of the menu, they had made the pancakes unfindable as a quest. First order of business was to put the pancakes with the pancakes.

The next flaw we identified was in the understanding of the ordering process. In the breakfast space, customers were used to “diner style” ordering, where everything is ordered as a full meal with all the sides included. IHOP uses “a la carte style” ordering but confusingly pictured items in a full meal setting throughout the menu with nothing more than an asterisk to tell customers that sides were not included as pictured. This led to many complaints from customers who ordered pancakes thinking it came with eggs, toast, and bacon only to have a sad lonely pancake plate delivered at meal time. In the new menu, we knew we had to make the a la carte ordering style more apparent.

With these insights in hand, we worked with the client to then eliminate items off the menu that were not deemed to be selling well enough to deserve the ad space – reducing from 16 pages to a more manageable 12 pages. We then developed regional strategies for meeting the needs of varied geographies and languages across the franchisee network.

And our plans paid off. It was even lauded by the press as having had a notable 3% increase in sales in the stores that tested the new menu. All in all it was a hugely successful project, which makes it a fun story to tell.

So do I tell you this story to brag? Kind of. But no, this story and my reason for telling this story today isn’t about the results we achieved in 2012, to get to today’s lesson, I had to wait 8 years.

Fast forward to summer 2020. We are living in unprecedented times and I am finally getting around to writing case studies of my past projects. I am working on one about IHOP.

I decided to link to some of the press articles about the success of the project, natch. And I suppose my googling the words IHOP and Menu Redesign got the algorithms all excited because days later, I received an eager message from Google that they had an article for me to read about the IHOP menu redesign.

Friends, I want to stop here and say I had literally no clue what was about to happen. I was very much expecting this to perhaps be another article about my work from 2012. That’s how unprepared I was here… ok back to the moment right before.

I open the article and find a shocking case study of the IHOP menu being redesigned in 2020 in the face of COVID19. It was reduced to a double-sided sheet of paper that could be printed in store and thrown away after each use.

There was a single sentence that applied to the work I had spent months of my life working on:

“IHOP is ditching it’s 12-page behemoth for a much cleaner 2-page menu” if you click the link on the word 12-page behemoth, you get another article where it is referred to as a “12 page laminated monstrosity”.

I hope you are starting to sense the turn in this lesson, friends. We are not here to congratulate me on my hard work in 2012. We are instead here to see that things that were made 8 years ago can create obstacles for a team to overcome in today’s context, regardless of the results achieved eight years ago.

This was a not so long ago reminder of the reality of doing this type of work. Good sensemakers are building structures that others will build upon, or decide to burn down when they no longer serve them. This doesn’t diminish the work of the sensemakers of the past.

Now I want you to think about this in context of the organization you work in. There is legacy there. There are things you yourself are creating today that some hot shot kid may describe as a behemoth to slay 8 years from today.

And just as that is the case, it is also the case that there are things you yourself are working on today that are replacing the work of sensemakers in the past.

This moment was a lesson for me because it was the most obvious and loud example of me having existed on both sides of this coin.

In 2012, 12 pages was a miracle of facilitation and change management. In 2020, that same 12 pages was a behemoth for a team under different circumstances to slay. I could not have gotten them to a 1 page menu, it was too great a leap for them to make at that point.

I could not have gotten them to a disposable menu. How would I have looked to be selling that idea in 2012 where environmentalism was on the rise and disposable everything was in question?

We are doing work, not magic. And work is never done. So I added the link to the new article to my website case study as a reminder and a lesson to all who end up there that nothing we make is forever, and that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

The first time through this story, the me of 2012 learned a lot of confidence being able to apply her brand of IA process to a complex thing that existed in physical, not just digital space. It was groundbreaking work I needed to do outside of digital IA to propel my teaching and thinking. And for that I will always be grateful. And of course, the client was thrilled with the results.

The second time through this story, the me of 2020 was dealing with the grief of my expertise and hard work being erased by the expertise and hard work of others, I learned a lot about letting go. I was reminded that while we must always prepare to adjust when doing sensemaking work, the adjustments don’t always stop when we are done.

I have heard for years people saying things like “Ugh I can’t show that anymore, it’s so old and they already replaced it” — and that makes me so concerned about the value we are missing by only looking at the most recent end points. There is value in the process of getting there. We are all on our own path, and the things, organizations and businesses that we work on are also on their own path. Many sensemakers may have come before on that same path, or perhaps you are blazing it yourself. Either way, others may follow and build there someday. And if you’re lucky enough to be around and notified by person or algorithm when they do, I hope you won’t miss the beauty of seeing how they can stand taller because of your having shouldered it before them.

Also the next time you are describing the problems inherent in an old system that no one has touched in a while, think about that aging sensemaker, maybe just a bit ahead of you in years, reading your judgements. I have learned that when walking down paths already trodden by others, if I turn to understanding the “because reasons” of it all, I can usually get further. When we seek to understand instead of just name-calling, we are more likely to build on what’s already good about what is there. When we aren’t curious about past sensemakers, we can make missteps they could have warned us of.

Mapping the Mapless

The third story I want to share is about the first project that was bigger than any example I had to follow as an IA around what to do first, next and last. It was the first time when the path from not knowing to knowing was anything but clear to me at the start.

The plan was to support a multi year AGILE process to design, build, test and release over time. In order to do that, we needed to create a feature + value matrix for evaluating each potential feature or piece of content and then establish an upper ontology of tasks and content types that the tool would support after each major release cycle. We landed with a clear picture of the growth of the tool’s architecture and functionality over time, mapped to the requirements the team had gathered, supported by the map and vision storyboard. This all allowed the team to talk about and get alignment and feedback on users’ needs for an interface before even investing in designing any screen-based details.

I learned from this experience that process isn’t always as simple as setting something upfront and then doing that thing. But when the going gets tough, the process is there to keep you focused on something other than the result being so hard or far away.

We need the process to stay on track, but we also need space in the process for times when we figure out that we don’t really know what we need just yet.

I’ll be honest, this project felt a little wild at times because it was so big and had so much complexity, the most I had seen at that point in my career.

A few months in, the project manager despondently told me that some days it felt like their entire job was booking plane tickets and updating the gantt chart when we uncovered another wrinkle to smooth in the map. This was the only other person who endured all 6 of those cross country trips to sit in a room with me and take notes while we walked through yet another version of the process with yet another role involved. We earned our Delta Medallions together that year.

Working so closely with someone who was so rightfully unsure of where this wildness was all heading made me realize that as a sensemaker, I had to be a model for this person in this moment. I had to show them how to drive through this hard part of not knowing to the better part of knowing. It was my role to make sure he knew this wasn’t weird, or something to be concerned about — but rather a predictable feeling of uncertainty and ambiguity that came with any big mapping effort for the mapless.

It wasn’t as if I didn’t have those moments of the should storm too. I did, believe me.

We should be getting more done, we should have more than a messy map by now, we should know what we are building by now. The client should know more of what this process is getting them by now.

On days when such storms threatened to rain on our process parade, I found it helped to remind myself and others that the result we were seeking was bigger than today. It was a map of a territory so complex that no one could map it any quicker. We had the permission, we had the access, we had the information. We just needed to take the time to make the sense.

I worry that people think that the making sense part should be immediate or it’s no good. Like nothing but love at first sense will do.

You need time. Time changes us, and it changes how we think about our work. It changes the work and what we can see. There are days I show up and wrestle with a document or diagram for hours, only to return the next day to the same mess, but this time prepared to fix it and move on.

I see too many people rushing through the sensemaking process when that is the surest way to cut off your curiosity about whatever it is you are working on.

We must remain curious.

“I wonder what the map will look like when we are done?” NOT “this is the template we are filling out.”

We must trust the process to lead us to the next right thing to do, to figure out the next right thing to know.

I find so much hope in that idea, that we don’t need to come prepared with all the answers and that expertise really isn’t about having all the answers, It’s about being brave enough to lead others towards finding answers.

When I was finding answers with the Nike team, we tried some really fun things. I had a series of workshops in Portland when we rolled out our controlled vocabulary where I wore a gym whistle around my neck to blow on anytime someone used a now-banned word. I’m not sure I would or could ever do this again, but I appreciated that they let me play and experiment with what might make the most sense for the moment to meet the team where they are.

The result of my work on the project was just momentum. It feels weird to claim momentum as a result, especially when I put in almost a full year of my time. But alas, I did not design the taxonomy nor the final interface of the actual tool that was eventually designed. My entire value was in unlocking the understanding between the two teams so they could design and build the best tool for them. They kicked off a 3 year agile based sprint cycle after our engagement, working with internal users on a phased testing and rollout.

On day one of my time with that team, they used different role based languages, had different views of the goal and a lack of understanding of where they were heading together.

When I left, they spoke the same language and had a crystal clear vision. They also had a map of the territory they were building together and phased plans to build a foundation and add to it incrementally.

That’s the power of sensemaking. I believe this is more than a story about effective information architecture. In fact I believe I could have done all the same information architecture steps in this story (made maps, written vocabularies, defined upper ontologies) and had very different results had I not been as strong a sensemaker.

25 year old me would not have lasted an hour on this project, not because her IA skills were not sharp enough — but because the need to make more sense than what she was ready for back then was palpable and yet incredibly hard to put into words.

I told you these three stories because they are all times in my career where I learned what it takes to make more sense.

After looking at my own journey to becoming a sensemaker, I became curious if other people could better identify and strengthen sensemaking skills in themselves and others if only there was a curriculum to start from.

When I was 25 I had my head in the right place, and my hands doing the right things but my heart had not yet been strengthened to the reality of what sensemaking work takes. I lacked knowledge of this weakness but even more, Iacked resources telling me how important these skills were to the work I had chosen to spend my life working on. I am lucky to have had a manager who could skillfully call this out and recommend a tangible method of helping. This is unfortunately the part of my story that is not a common one.

Many people jump from job to job with no one ever helping them really understand the friction they feel with others or within themselves.

I became curious if this lack of wholeness when developing sensemaking skills is in fact common and if it is, how I might help people like 25 year old me not have to make so many embarrassing missteps early on.

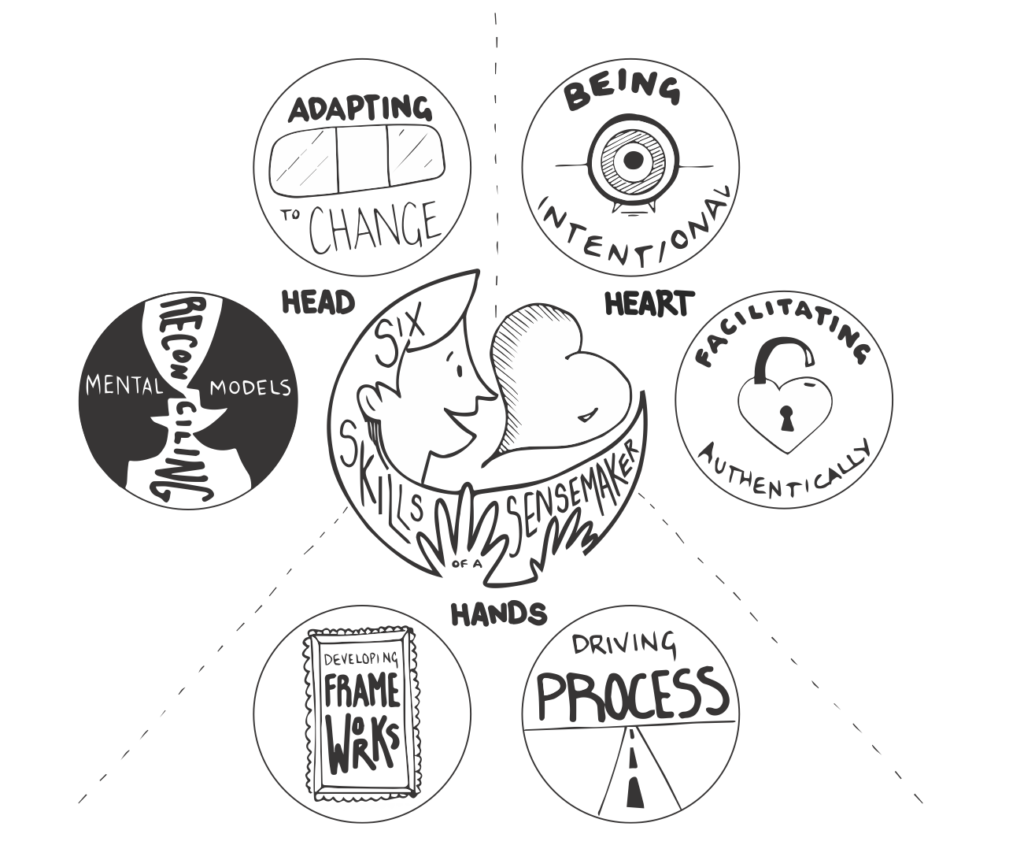

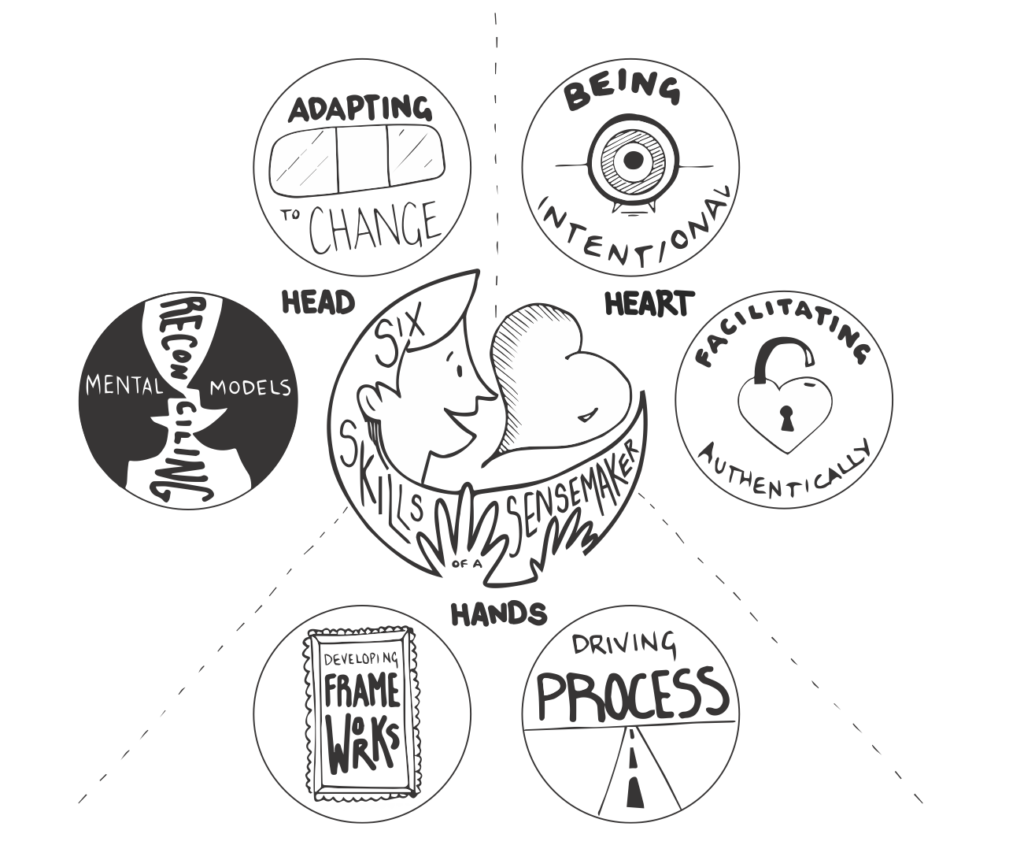

Ever the information architect, I felt compelled to pick labels for the sensemaking skills I saw myself having to spend time on strengthening as my work grew in complexity. Labeling things makes them teachable so I started working on a taxonomy of sensemaking skills.

As I got into it, I started to think about ways to arrange these skills, and I was reminded of my story from Chicago. When I look back on that story and the countless others where I am working on myself as part of my IA work, I think most about working on my heart.

Using the heart as a metaphor made me curious about what other metaphorical parts of ourselves are strong or weak as a sensemaker.

I identified three areas of myself: head, heart and hands and started to sort each sensemaker skill I had identified to the part of myself that each skill felt most strengthened by.

I designated the thinking to the head, feeling to the heart and making to the hands.

This felt like a dumb model at the time, but honestly after months of playing with it — I have kind of fallen for it. While the reality of these actual body parts is that they are all inextricably linked to all of these skills, I think there is a beauty in the compartmentalization for the purpose of examining and strengthening. I have been thinking about it like when it’s leg day at the gym. That doesn’t mean that your arms don’t also show up and get some of the workout — it just means that your focus that day is on exercises that work extra hard on your legs.

I learned so much about my own imbalance through this exercise that I became curious how a framework of these types of skills arranged this way might enable other people to better identify their own weaknesses and focus on seeking wholeness and balance as they grow in their careers instead of hyperfocusing on their strengths, which I now realize that 25 year old me was doing a lot of.

When I was 25, my mental model was that my head was in charge of all the things. It was as if I was practicing IA as a head in a jar. Perhaps this is one of the many reasons my early coworkers assigned me the nickname Abby Normal.

Since I was a kid, writing and drawing have always been my go to for getting things out of my overactive brain, so I found that my hands were always an easy skillset to keep track of as I grew in my career.

The part that took me much longer to identify weakness in, is the part that I think of now as the missing piece to my sensemaking super powers.

This metaphor about parts of my sensemaking self helped me to understand that there are some things I can’t think and make my way out of. There are always going to be some feelings, mine and others, and I will have to deal with those feelings, not just pity myself for having befallen other human beings forever.

I needed to develop this deep weakness of mine into a strength if I wanted to make more sense in an ever complexifying world. And more than a decade of introspection and therapy later I can say I have made some progress.

I now understand that getting stuck in our heads and acting out our thoughts with our hands only gets us so far. If we want to make more sense, we have to use the feeling parts of us too.

If feeling was the missing piece for me I became curious if there might be people with weaknesses where I draw natural strength, in the thinking and making.

Maybe there are people who are feeling and making their way through their sensemaking work without thinking too much about it.

And other people who are feeling and thinking while never making much at all. Maybe some people are just thinking all the time. Or feeling all the time.

…or making all the time.

Now that I laid it all out, I’m pretty sure I just described every fellow twenty-something I encountered at meet-ups around that same time in my own life. Heck, I might have just described every person who feels like they don’t make enough sense.

After spending time on making sense of this for myself, I have become so curious if teaching this kind of wholeness is the intention I should pursue next with my time. It feels like such a thing could be useful to the world where so little sense seems to be made most days.

Six Skills of a Sensemaker

And so we have reached our final chapter together today, where I introduce you to my new framework of six sensemaking skills.

I believe that if you want to make more sense — this is a good list of skills to understand your strength or weakness in.

None of these skills is easy, to teach or to learn and I consider that a feature, not a bug. I don’t provide this in an attempt to make an end-all-be-all model to apply to everyone. Nor a teachable model for others, just yet. And yes, you may read that as foreshadowing.

I offer this model as a call to action for every sensemaker to think about what it takes to make more sense in your own context and to ask yourself deeply how whole you feel in the ways you are practicing.

With the time I have left with you today, I want to introduce you to six skills that I am working on strengthening in myself as I search for ways to teach these skills to other people.

I want to start with the heart, as that is where my story of finding my own imbalance led me. There are two skills I have identified that I think need to be strengthened to have the heart of a sensemaker. Being intentional and facilitating authentically.

Being Intentional

Being intentional is, above all others, the sensemaking skill that allows us to do hard things in spite of and because they are hard. Being intentional involves actually knowing your intention and then being like that. It takes putting enough space between your feelings and the actions you ultimately decide to take that you stay true to your intention.

When you are making something, you can never serve all people, all goals, all outcomes. We must decide. Stating an intention is the act of deciding. But being intentional is living out that decision even when it disappoints or upsets other people, and that is much more often the hard part.

When I wrote a book about information architecture at a sixth grade reading level with no complex technical examples, it was in an effort to meet my intention of writing a beginner’s guide to IA.

If you read any of my lower star reviews on Amazon, you will see how that really ticked off some folks who believed I should have written that book for them. If you read my high star reviews, you will see how that same choice helped many more than it ticked off.

But the part that the heart-weak amongst us can struggle with is that we cannot make all people happy. Even harder is some pursue “making all people happy” as their intention only to learn a painful lesson in how little we really control.

When doing hard things, we have to decide the way we are going, because reasons and then go that way until that way no longer serves our intention or until our intention changes. Once the decision is made, we must continue to be intentional, not waffle on our decided direction because we don’t know what to do with other people’s disappointment.

Like many things, it is easy to set a goal, and much harder to make the thousands of tiny decisions and actions to reach it. Being intentional is a skill that takes bravery to strengthen. It’s not fun to get bad reviews or to hear that you didn’t help someone with something you made. But if you spend time on the skill of being intentional, it’s easier to catalog that feedback into the right place for it to be dealt with or sent to the incinerator of “not my user, not my job.”

While being intentional is largely impactful within yourself, the second skill of the sensemaker’s heart is one we turn to when collaborating with or serving other people. Next I want to talk about what it means to facilitate authentically.

Facilitating Authentically

⚠️ Double Buzzword Alert ⚠️

What happens when you slam two buzz words from different industries together? I suppose we are on a journey to find out here today.

I have wrestled with these words, friends. I know that some of you are already checking out from what I am saying because of my choice to go down this mindfulness path or because you are rightfully sick of everyone telling you to work on your facilitation skills without much more than that buzzword to go off of.

But I have turned it around so many times, and relabeled it for your comfort and mine even more times and here is where I am landing: I want to be intentionally woo woo. And here’s why.

These are the right words because they are so wrapped up in nonsense at the moment that they are losing the sensemaking power that I believe they uniquely hold. What if instead of rejecting these two words for being overused, misused, watered down and woo woo, we take them and teach them as a skill that a whole generation of sensemakers may use to turn that nonsense pile into arrangements that make lots of sense?

I have spent a lot of time in alot of workshops. I have watched a lot of people run a lot of meetings and I have run a lot of workshops and meetings where the agenda wasn’t about authentic facilitation. It was more about getting out unscathed and with a predictable outcome. Like I could write the script of what would happen and pull the strings like a puppet master.

People don’t work like that. Life doesn’t work like that. Unfortunately when it comes to facilitation too many people are taught about the gimmicks, like time-boxes and parking lots, but are never taught to facilitate a conversation where they are more listeners than leaders. They aren’t taught how to deal with their emotions let alone their part in the emotions of others.

When it comes to authenticity, most people are left out in the cold education wise. So many of us stumble through our own realizations about ourselves and our own weaknesses of the heart through our own experienced mis steps. I know this is the way we have always done it but as a mom now, and a teacher always, I wish we could give more people a heads up.

I wish my list of people I personally know who could benefit from this listen was in their mid twenties, like I was in my Chicago story. But no, many of the people I encounter who need to work on this skill the most are well along into their life stories. Some of them even hold high positions.

People who lack authenticity can rise quite high into the ranks without the knowledge of their weak hearts. I have spent good time with bad models enough to know how lonely and sad rejecting authenticity really is. People who can’t facilitate authentically live in the should storm, where we should respect their expertise. Their frustration drives their actions and clouds their thoughts.

As I mentioned before, when you really look at all those shoulds you often really just have a lot of fear. People who aren’t able to facilitate authentically are often really just afraid of any outcome that isn’t theirs to control and/or claim.

People who are able to facilitate authentically are able to get to the truth of the matter and make progress with those involved, regardless of the feelings that might arise in themselves or those they are facilitating.

Adapting to Change

Next I want to talk about the two sensemaking skills that I believe to be strengthened by the head of a sensemaker. I go to these next, because I think they have quite a lovely duality in context to the skills of the heart.

While we are being intentional, we must also be constantly adapting to change.This might feel counterintuitive because the concept of setting an intention and sticking to it doesn’t much leave room for the idea of adapting to change at all.

Which is unfortunate because in my experience it is our malleability in moments of disharmony with our intention that is critical to develop. Our head’s malleability supports our heart’s ability to be intentional by allowing things to change without disruption for discomfort’s sake.

Adapting to change is a skill one can apply within one’s self, but it can also be the job of a sensemaker to help others adapt to change as part of the thing you are making. Part of being a good sensemaker is thinking through and anticipating the changes you might need to implement overtime in an attempt to limit the discomfort felt by the team when eventually changes need to happen, which they always do.

One of the reasons the IHOP menu architecture I worked on latest as long as it did was that it was very adaptable to change. We were able to discuss the nuts and bolts of the business upfront and anticipate a lot of needs. The graphic design of the menu changed many times seasonally over the 8 years between major architectural redesigns. Ultimately it took a global pandemic changing the fundamental nature of casual dining to break the architectural model we made.

And even in the face of that, IHOP and the team in place in 2020 were able to adapt to change, taking on some pretty bold changes to meet the needs of a tumultuous time.

Reconciling Mental Models

The second skill of the head of a sensemaker is being able to reconcile mental models. When we are making sense with other people, we are dealing with a lot of information.

Literally. For every person that you involve in a project, imagine there is a map in their mind of everything that they know. And the thing you are working on together: it’s on their map. But it’s represented based on how the rest of their map is arranged, prioritized and ordered. It’s based on what they care about and the things that their experience has shaped their knowledge to be.

These individual maps of knowledge are called our mental models. We all have them and we can’t see each others’- no matter how hard we might try. Devices like language exist so we can compare and express our mental models of the world with one another but we ourselves cannot see our own ever-changing mental models — even though they influence our habits, emotions, sensations, thoughts and impulses.

When we are making sense for other people, each of them come to that problem with their own background, experience and knowledge. Their own mental model that influences how they act, feel and know.

There is an artful skill to being able to spend time with people with the express goal to understand their mental model, there is also a separate but equally important skill in being able to identify and understand your own mental mode and then be able to reconcile yours with theirs. The goal being to identify when contradictions or conflicts between mental models is in the way of safety or progress towards your intention.

I think much of the success of my work on Nike came down to reconciling mental models. There were so many examples in that project where something as simple as a mismatch of language between two teams became the sticking point that continued to rear its head until it was reconciled and progressed through.

The reconciliation of mental models isn’t always about documenting the mental models and showing them to the people who hold or contradict them. Oftentimes reconciling mental models is a thread you have to weave through the whole process. Taking the time to make sure all mental models are accounted for as the journey takes its inevitable peaks and valleys. I chose the word reconcile because to me it feels both final and never done in equal measure.

I think if you spend time with this skill for your professional benefit, don’t be surprised when it helps personally as well. I can tell you that being able to reconcile your own mental model and the mental model of a loved one during especially difficult times can be a true gift.

Driving Process

The last set of skills I want to talk to are strengthened by the hands of the sensemaker, developing frameworks and driving process.

From my Nike story I got to thinking a lot about the impact of a process (and lack of process) on a team, but more specifically how actively I have to drive a process as a sensemaker.

Determining the list of tasks up front is easier than making it all happen. It’s a list of amorphous task blobs made of clear words that somehow lose the weight of their reality through the lightness of their labeling.

Propose a Research Plan, Host a Speaker Series, Create a Launch Strategy, Vaccinate the Population…

These all seem a bit too easy when written out on a checklist. Driving Process is the set of skills that takes that vague checkmark and turns it into momentum, getting the plan together to move all the right people, and all the right pieces to all the right places to get that thing to happen, whatever that thing is.

Sometimes our process goes off road, I can tell you that was the case MANY times in that Nike story. Times when I looked at the map on the wall in Portland only four interviews into a week of 12 thinking “what have I gotten myself into — this is not make sense able!”

Friends, this is normal. This is the heart freaking out a little because this is the work of facilitating authentically — listening to 12 people go into EXCRUCIATING detail about their roles in a process so complex that until a few weeks ago you never would have imagined it took this many people to get a single pair of sneakers onto feet on the street.

When this little freak out of the heart happens, the skill is for me to keep driving. Even though it’s hard and I want to pull over.

Now I want to pause here — to make sure we talk about burn out. I am not advocating for you to DRIVE hard until your body gives out heart, head and hands.

🚫 BURNOUT 🚫

Please listen double hard to this part: Part of driving is controlling the speed and safety of the driving we are doing. We must determine the right speed when establishing our direction with our intention. We have to be honest about what things will take. If our speed and intention are in conflict, we will never reach our destination and could die trying too.

Defining the process is part of the role of a sensemaker, and an important one. But when I talk about driving the process, coming up with humane milestones for yourself and your collaborators must be an inherent part of the work. Perhaps I should have mentioned before that taking care of ourselves, the makers, should always be part of being intentional. Because without us, who else can reach our unique intention?

Developing Frameworks

One thing I see a lot of is the muddying of process and framework. People say things like:

“Make a Customer Journey Map” or “Make a product roadmap” while still in the “Defining the Process” phase, instead of focusing instead on the value they are seeking from the process at that phase. Jumping to a specific framework quickly or associating certain frameworks with timeframes in processes might feel like repeatable magic, but ultimately it can be incredibly limiting, which is less repeatable magic and more just repeatable.

If a team is asked instead to “Understand our customer’s experience with our current ordering process” or “Think deeply and cross functionally about the how the product might change over 1, 3 and 5 years” — a very different process might be spurred, one that is more likely to actually be useful to the work vs. a tried and true framework that only might be useful.

That’s why I wanted to separate out the sensemaking skills of “Driving Process” and “Developing Frameworks” to make a little space for the consideration that they don’t always and perhaps shouldn’t always be so mixed up in one another. I worry that when they spend too much time overlapping and they start to create the conditions for “that’s the way we’ve always done it” thinking – which I see as the main source for the dampening of curiosity and innovation for many teams and organizations.

I am a firm believer in the verb developing when it comes to frameworks as well. I am frankly sick of seeing people recycling the frameworks of others when that time often is much better spent developing a unique framework for the unique circumstance in which you find yourself.

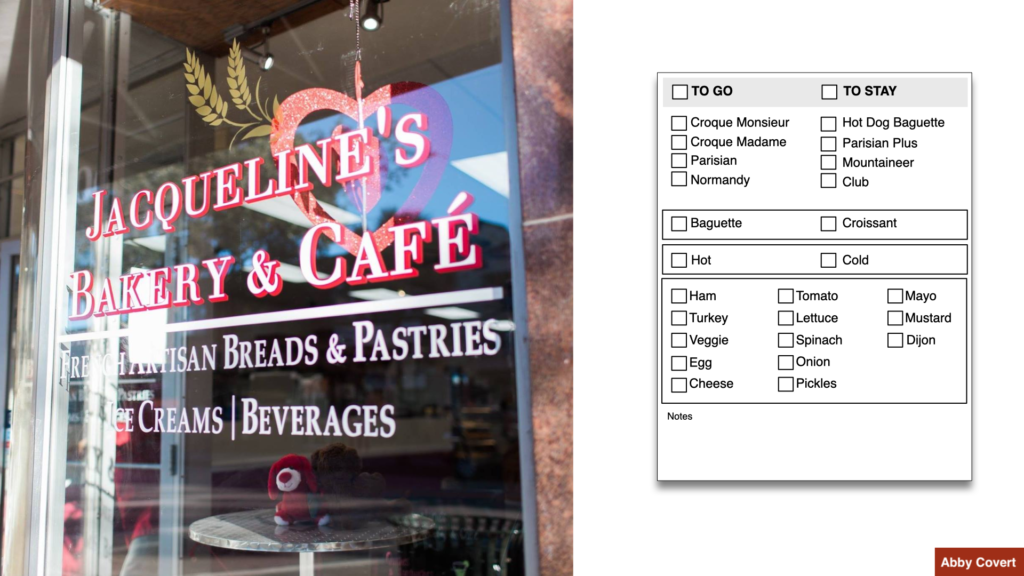

My sister, who is now a pastry chef, had her first baking job at a little french cafe. In addition to her baking tasks, she was in charge of making sandwiches to order during the daily lunch rush. Over time she had become quite annoyed that the wait staff were all over the place in terms of how they wrote out customer sandwich orders on a small notepad next to the register before handing it to her. It almost always resulted in a verbal back and forth of clarification which could feel stressful in an already turbulent cafe environment during lunch.

She asked me if I would help her design a custom note pad that had all the sandwich options that bakers wanted the wait staff to be more consistent in filling out more clearly. We made a prototype and she took it to work and got the owner on board with the idea. They ordered a custom notepad and within a week — the whole thing made a whole lot more sense.

The process had not really changed all that much, the piece of paper was on a notepad at the register. The wait staff still asked customers the same list of questions about the same menu items. The piece of paper with the details was then passed to the baker to make the sandwich.

What had changed was the framework that the process used. Identifying and alleviating this problem was my sister driving the process by developing a framework.

It’s sensemaking, as classic as it comes.

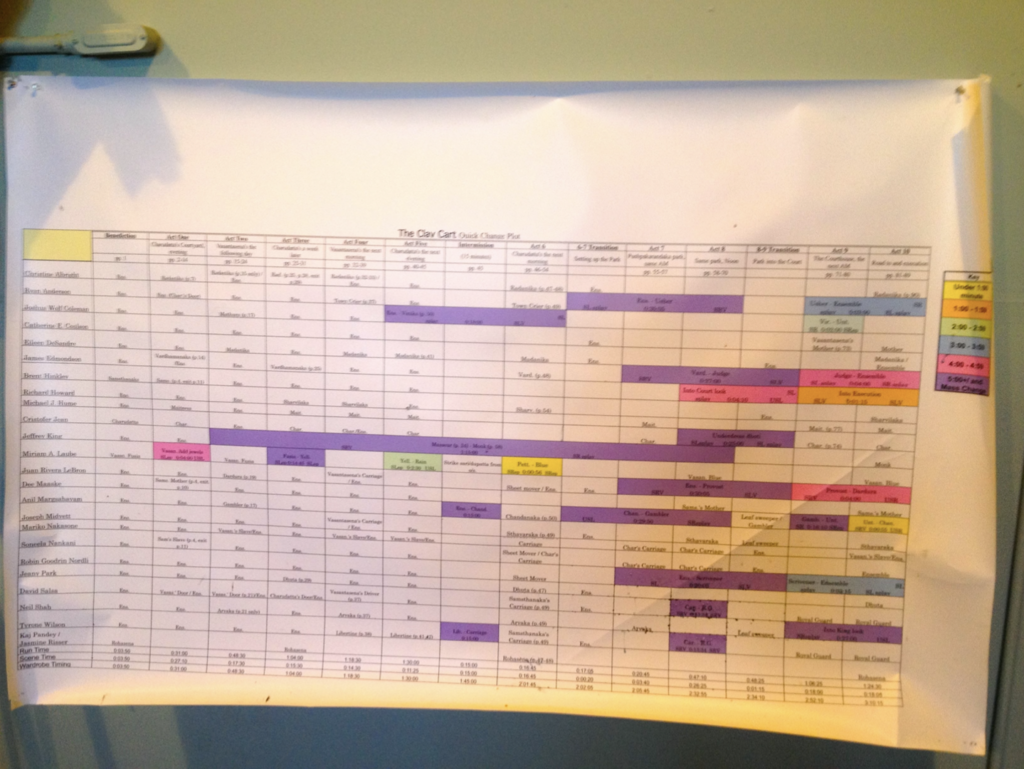

I was once touring the backstage of a show in the Ashland Shakespeare Festival. I ran into a messy but perfect framework shown in this rushed blurry photo. This framework really cemented for this understanding of how deep sensemaking goes and how many roles it touches in this world.

This framework is simple, it’s a color coded list of costume changes. If the costume change was less than a certain time range, it is highlighted in a certain color.

This allowed the actors to understand the most important information first when coming off stage — whether they are able to completely relax or whether to anticipate a whirlwind of people undressing and dressing them at a frenzied haste as if their bodies were at a pit stop.

What a lovely use of a framework, to save the emotional energy of a colleague by answering their most anticipated question at a critical juncture: Will people need to be touching me in haste? Will I be getting nude in this vestibule? I can say in 16 years of IA practice I have never needed to develop a framework to answer this question for users. But I sure am glad other people are out there developing frameworks to drive whatever process is needed to get their intention into the world. It proves the uniqueness of all of our individual contexts and reminds us that not all things are one google away.

Frameworks and Process largely control what our hands are doing while sensemaking, but the connection to the head and heart is not without massive importance.

In making this framework I have realized that my real lesson is on the importance of becoming more whole as a sensemaker. Some of the things on this list came quite naturally to me. There is a reason my sister knew to come to me with the bakery problem.

I have always been a framework developer. I have also always been curious about the process things take and how the steps can be planned for and executed to get big things done over time. I suppose you could say I was born with the hands of a sensemaker.

As an information architect who came up in the user experience community, I had a good basis for the conceptual underpinnings for change management, mental models, goal setting and facilitation — all of which still serve as the basis for my work and my expertise.

It was the realization that it actually takes more than theoretical knowledge and experience with the right skills and tools to be whole as a practitioner in pretty much anything. We have to make sense along the way. More and more as we advance in our knowledge and craft.

I worry that if we aren’t careful we can spend our whole careers acquiring knowledge and getting better at understanding the craft and mediums of our chosen fields leaving the sensemaking skills to whatever natural inclinations we have or whatever smattering of education we have been given.

I have developed this framework of sensemaking skills because I think we all need to collectively start making a whole lot more sense, at work, at home and in our own selves.

We can’t keep trying to find places to put things when the meaning of those things is not yet clear. In my opinion, that’s how we got into a lot of the messes we are likely to leave for the next generation to solve.

If all I did in writing this piece for you all today was invent a framework to see the growth potential I still have left and the areas I am now more than ever inspired to find ways to teach to others, well then that’s enough sense made for me.

It makes sense to work on yourself, head, heart and hands to cultivate your sensemaking skills.

If you work on being intentional, facilitating authentically, driving process, developing frameworks, reconciling mental models and adapting to change, you will make more sense.

I promise.

—

My email list is the best way to keep up with me and show your support for my work. Thanks in advance for subscribing below or sharing my work on your networks.