Early Childhood Information Architecture

“Actually, that’s an armored catfish, mama.” he bluntly said, tinychild-splaining at me before I had even finished my statement. He quickly followed up with “also watch out, that plant is poisonous.”

My kid’s ever-expanding collection of both vocabulary and metadata schemas grows right before my eyes everyday. Supporting him in his first year of preschool has made me think alot about when and how we are actually first exposed to the concepts that are core to information architecture.

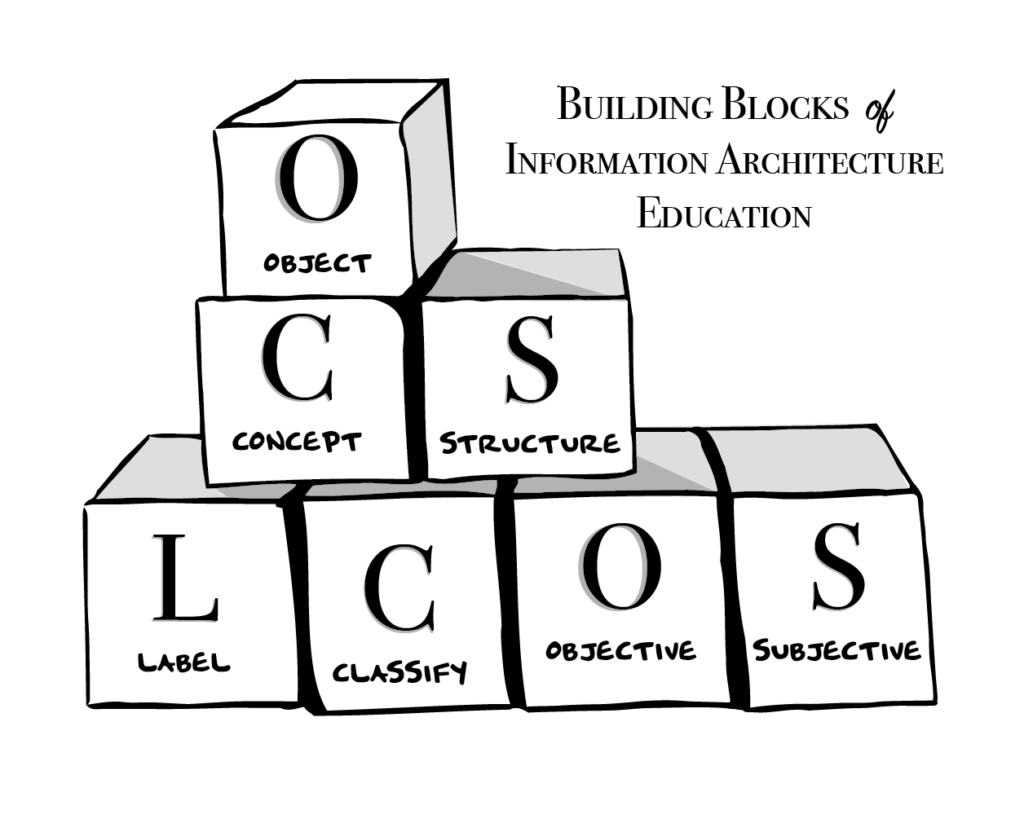

- 📦 Objects: Things in the world

- 💭 Concepts: Things not “in” the world but “about” it

- 💬 Labels: What we call objects and concepts

- 🏛️ Structures: How we arrange objects and concepts

- 🏗️ Classification: Rules that determine how we sort objects and concepts

- 🧠 Subjectivity: Understanding that changes based on each interpretation

- 📏 Objectivity: Understanding that can be reasonably relied upon to remain constant across individuals and interpretations

While I doubt any preschool classroom is using words like classification or subjectivity – from my experience as a preschool mom, these lessons are taught quite early under other labels and relied on often from then on out to introduce and reinforce the way our world works for small developing minds.

Stages of Early Childhood IA Education

In this article I share what I have learned about how we learn information architecture as small children because there is an important lesson about the role of objectivity and subjectivity that can help folks to improve their IA skills later in life.

Stage 1: Understanding Classification & Objectivity

To kick off our early childhood IA education we are taught that categories of and labels for objects exist. You might be surprised to learn that what seems like a simple underpinning of the human experience is actually a lesson we go without for a long while as a baby and slowly pick-up over the first few years of early life as our communication skills develop.

The ability to sort objects into categories based on objective rules of classification is seen in the majority of children by the age of two. In many children this is observed before being able to clearly verbalize labels for those objects or categories.

In other words, we learn to sort before we learn to talk.

Around this age, children also start to develop an understanding of many labels for singular objects as well as the idea of singular and plural objects.

For example, around two years old my kid started to understand that I am called “Mama” at home, “Abby” to people we know, “Jamie’s Mom” at playgrounds and “Ma’am” at the Grocery store but that I am still just the one, singular me. This also explains why he now answers to “Mister Bug”, “Bug Man” and “Doodle” in addition to his legal name.

At this age sorting and matching games help children to develop a clearer understanding of objective reality. These objective broad categories often include examples like letters, numbers, colors, snacks, shapes, animals, bugs (or if you are my kiddo: construction equipment)

These simple classifications are how we understand our world. When they encounter things that don’t fit neatly into the pre-established taxonomies they know, a two year old will let you know!

At this point in a child’s development we are still only working at developing their objective perspective. The paint that is a child’s understanding of object permanence is not yet dry and because of that they are fairly unaware of subjectivity as a concept.

In case you ever wondered why two year olds think they are right about everything, this is why. They are still the objective center of their objectively understood world and their rules can be a bit … er, twisted.

For example, at the age of two my kid decided that basically any vehicle that was bright orange was construction equipment – even a bright orange race car or bicycle. There was no use in arguing. At this age the concept of “sometimes” is often not accepted.

Stage 2: Inferring Objective Meaning from Acquired Knowledge

Between three and four years old we start to be able to infer objective meaning from structures. While a two year old can confidently sort vegetables from a larger group of grocery items when instructed to do so, a three to four year old can tell you that a group of objects are “vegetables” based on their acquired, complex knowledge of what each labeled object is as well as how they are the same or different from one another at the facet level.

They might even tell you the group of objects are “green vegetables” or “yucky vegetables” because they are starting to see more than just top level categories for objects in their world. They are starting to develop preferences as well as acquire more knowledge about how things are made, rated, acquired, used or discarded.

By the age of four the majority of children are able to classify objects based on a more complex set of rules or facets. At this age we can start to identify and label subgroups within larger categories as well as list attributes about the objects we encounter.

For example: An elephant is “big”, “gray”, “lives in the jungle”, and “eats plants’ or This apple is “green”, “ fruit”, and “yummy in pie” – BOOM! … baby’s first faceted metadata schema.

That same four year old might also be able to tell you apples “can also be red or yellow” or that apples “have a core with seeds we don’t eat”– which is expressing that they know more about a concept behind an object, not just what they see in this particular instance of the concept.

This Venn diagram from the king of picture riddles,Walter Wick, shows the power of complex inference that children are able to develop by a young age.

My kid’s head just about exploded the first time we looked at this page. Because while it is breathtakingly beautiful in an artistic sense, it’s also complex. It takes some real cognitive processing to understand the details of it.

At this age we only really have objective labels for objects we know and the structures we have been introduced for those objects. It is at this point that subjectivity starts to dawn on us because our acquired knowledge of labels and structures for objects by this point varies based on our surroundings and context.

Stage 3: Declaring Subjective Meaning

Between four and five years old we start to have the ability to make our own labels and rule-bounded structures for objects. This largely comes from the expanse that is … you guessed it … our imagination!

If I can be so bold as to say, around this age we are practicing something much more like imagination architecture. Because the things we are making do NOT make sense, almost as a rule, to other people.

Scene: A yellow ball with yellow lines radiating from it is presented with expectant eyes

Context: We drew a sun that looked just like this yesterday.

Me: “What a beautiful sun!”

Him: “It’s not a sun, it’s a splat”

Around this age is truly our first taste of subjectivity. And it’s a wild leap in our information architecture education. It opens up our ability to have fine-tuned preferences, and to create whole other worlds to explore using our mind.

Around this age is truly our first taste of subjectivity. And it’s a wild leap in our information architecture education. It opens up our ability to have fine-tuned preferences, and to create whole other worlds to explore using our mind.

FWIW it was good to learn this is why at four years old my kid suddenly became obsessed with working the word “poop” into every song, rhyme, and turn of phrase.

At this age you could ask a child to organize a grocery pile into categories and they could do it, and quite confidently. You could also expect them to be able to tell you their rules for classifying the grocery items the way they did. You might also experience them defending their choices (in some cases vehemently as any toddler caretaker could tell you).

Their categories might be a range of useful to nonsensical and if we were to ask five children to do that same task, we could expect five different results.

Once a kid can confidently complete a complex, subjective sorting task like that without your cognitive assistance – congratulations, they are now an information architect and will remain so for life!

They will use these core IA skills to organize their objective reality (i.e. how they arrange objects in their spaces) as well as their subjective reality (i.e. how they organize their thoughts and communications in support of an intention) for the rest of their life.

What can adults learn from how kids learn IA?

If we ask five adults to do that same grocery sorting task, guess what we could expect to happen? The same (different) results.

Even adults sharing a household are unlikely to have the exact same approach to classification even for something as simple as a pile of groceries.

We adults aren’t performing the task in the same subjective ways we did as kids. Since then we have acquired more knowledge about food categorization, grocery shopping, preparing food, our preferences and food storage that will impact how we approach classification of grocery items.

But if we were a tech company coming up with the taxonomy for a grocery delivery app in a small group of adults I can guarantee you from experience that there would be discussions about right vs. wrong that would be much better had about subjective vs. objective when it comes to classification.

As one simple example:

In a grocery store setting tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, zucchini, and avocados might be argued as subjectively “vegetables” in a world where they are objectively “fruit”

… but I doubt you would want to add any of these objective ‘fruits’ into a subjective ‘fruit salad’ – yuck!

If we aren’t thoughtful about how things are classified we take for granted the unique combination of mental model and imagination we are using when we are practicing information architecture. And we also use that unique combination when we are interpreting the world around us. Information architecture is much more art than science.

In any information architecture education as an adult the duality of objective vs. subjective truth has to be acknowledged as a core reality of the primary material you will be working with: Information.

Information: Whatever is perceived from an arrangement or sequence of things.

In other words, we can’t make information for other people; Information is entirely subjective. We can only make content we hope makes sense to them, and result in information in line with what we intended.

This means it is always worth determining how subjective or objective something is when it comes to information architecture work.

For example, “color” may feel fairly objective in your current reality, but in some contexts the subjectivity of it might become a big part of your IA reality.

When I worked on an eCommerce platform with a network of sellers adding their own product color metadata there were a host of issues that were created from a basic lack of agreement on the subjectivity or objectivity of labeling colors.

A product that is “blue-green” to one person, might be “green-blue” to another, “Ocean Breeze” to a third, “Turquoise” to a fourth and … wait for it … “Color 5b” to a fifth. Apply this to tens of millions of items … and what a mess!

This messy metadata created a major issue for folks looking to shop in this marketplace. Shoppers were shown neat and tidy color filters in the search UI that promised a metadata reality the platform could not provide, which led to the search seldom delivering useful results based on color.

As I was briefed on this issue, I found out that the first trial at fixing this issue had also failed. In order to make something subjective more objective, the team proposed taking color data from the product photos instead of relying on the messy color metadata as entered by sellers. Because hex codes never lie … right?

Sigh. The result was gold jewelry shot on a red background was now “red” and a yellow hat shot in a grassy background was now “green” – which was subjectively AND objectively incorrect.

There are obviously more elegant technical solutions (many of which had to be explored to understand this issue fully over years) but the part of this story that interested me most was that an entire team of adults had relied on more false objectivity to solve a problem initially created by thinking about color too objectively by assuming people would magically agree on color names and ranges of value without any form of governance.

The lesson I hope you take away is that sometimes as adults we have to revisit even our most foundational, tidy, and seemingly objective toddler categories in more subjective ways that feel new and uncomfortable. As always the first step is admitting it (may be more subjective than you realized).

In teaching adults information architecture the most heartbreaking lesson is always when a student seemingly suddenly realizes how much of their “objective” reality is actually incredibly “subjective” – and then ultimately also realizes this is nothing new. In fact it has been the way things have been since preschool.

—

Thanks for reading!

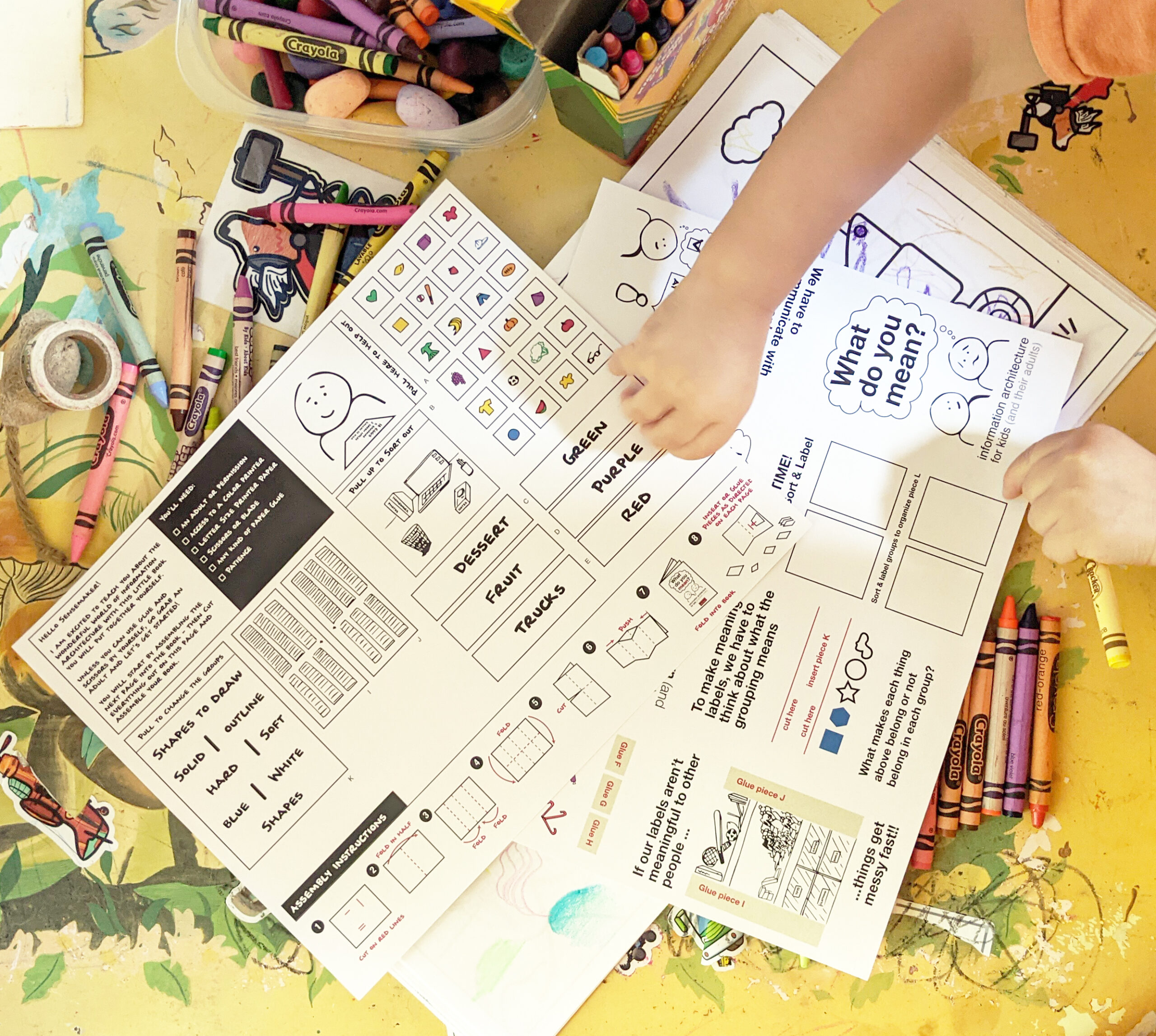

✂️ If you hang out with a kiddo from 5 to 9 years old I have a print and assemble kid’s zine about information architecture. All you need is a printer, cutting instrument and some glue. Also, I recorded a video so you can assemble it with me as your guide.

📽️ If you are looking to dig deeper into what IA is I offer a 30 minute FREE video eCourse called Information Architecture for Everybody covering basic concepts, methods and common questions people ask while learning about IA.

🤓 If you are ready to go from curious to confidently practicing information architecture in your own context, consider becoming one of my students by registering for The Practitioner’s Guide to How to Make Sense of Any Mess. This course includes access to my LIVE monthly office hours.

💌 If you want to keep up with the latest from me, join my monthly email list. And if you found this to be of value, I would be so appreciative if you sent this piece to anyone else who might also find value in it.