Incentive Architecture

Incentive Architecture before Information Architecture

I had a conversation recently that left me confident about the best advice I believe I could personally give to anyone managing other people, but specifically if you’re managing people who have to work with other people.

The question that plucked at my cynical heart strings was this honest one during a one-on-one office hours appointment recently:

“What if you need to convince someone to change?“

A few years ago I think I would have encouraged this person to re-word, re-frame, re-educate or re-iterate their points persistently until they could get their way or give up in a huff and move on for greener pastures.

But instead there I sat with new knowledge burning a hole in my pocket.

“If they are the ones with the power, you can’t convince anyone to change what they are doing. Unless somehow you can change their incentive.“

– me surprising even myself

I have had enough experience helping organizations and individuals make sense of their information architecture messes to understand that someone can see a mess, admit it’s a mess, and even complain regularly about a mess — but it’s not until something changes in their incentive that people actually make sense of their messes.

This is really frustrating to us sensemakers. We have a special attunement to messes, as well as the imagination architecture skills to see what the world could be like “if we could have nice things”

In reality we sensemakers are not always the decision makers. We are not always able to get to the change without decision makers changing.

This metaphor might get weird but, we are more often the cart looking for a horse. And without that horse to get us moving, we are just a cart waiting around to be useful. Carts are only useful when hitched to someone else’s momentum. So a cart has a ton of down time.

We can’t put our cart before the horse. We also have to recognize when the horse we are attempting to attach ourselves to doesn’t want a cart at all — because they are incentivized as a race horse, or a show pony.

Sometimes we have to sit around waiting for a cart-less horse for quite a while before we find one who wants to help us carry our load. In this metaphor; as is in life — this involves incentive alignment.

Incentive is what motivates us. Having the same incentive as someone else is the surest way to get something done quickly and without drama. Having hidden or reversed incentives are some of the quickest ways to guarantee drama.

For example, I know a pastry chef who works in a large, corporate kitchen of a retirement community. When she first started she was struggling to feel heard while pushing her management to let her do increasingly exotic and intricate plating designs for her creation.

As a baker she was incentivized by the residents being thrilled with her bakes, and by the Instagram-able quality to whatever she made.

The business was incentivized by consistency of resident experience, training costs and kitchen efficiency. They never wanted residents to remark on the days the professional baker had off that the experience in the restaurant was less appealing. They needed other, less skilled people to be able to replicate her plating designs without a lot of training, and they needed to be able to have easy, assembly-only desserts that could last over periods of low staffing.

By focusing on better aligning incentives, she was able to have a heart to heart about her position and the balance of ease for the business, and creatively fulfilling she would need to keep working there happily. They agreed to let her go all out on special events for holidays, resident events and special community milestones. She agreed to work off a more constrained, but still high quality, dessert menu that is easy for everyone else in the kitchen to assemble without special training. By aligning their incentives, everyone got their cake and ate it too.

As you can see in the below table, various types of roles have widely varied metrics and information by which they are commonly incentivized.

| Role Type | Commonly Incentivized by … |

| Product | Short term lift metrics like conversion, revenue or active daily users |

| Design | User experience quality, aesthetic desire, and altruism towards users |

| Technology | Hard-line production metrics like down time, push velocity, technical resource efficiency |

| Marketing & Brand | Longer term metrics like brand health, comparison to competitors, audience and reach |

| Management | Internal perception or metrics of team performance |

Since each type of role tends to have its own type of incentive, without thoughtful management the differences of incentive between roles can become a major collaboration hurdle.

Based on the above table: if you are a designer selling an idea to a product team based on altruism for the user, you are fighting a losing battle. This also means if you are a marketing person selling a brand health initiative to a tech team you are fighting a losing battle.

I will let you finish the mix and match game based on the above on your own. I have seen most of the combinations that are possible above, and can attest to the messes of emotion and loss of business results that come from the misalignment of incentives.

Advice for Managers

What I am talking about in this piece is something I honestly believe more managers should be taking on the emotional burden of, instead of sending sensemakers into the wild like door to door encyclopedia salespeople.

If you aren’t helping your employees to manage incentives amongst their stakeholders, you aren’t actually managing them. You are watching them fight a losing battle. Worse yet, you are maybe even giving them feedback that they need to sell their ideas better.

One of the hardest plights of being an external consultant is being called in to point out a mess everyone else already sees but has been unsuccessful selling to the decision makers.

If in-house folks (and their managers) aren’t kind to themselves they can believe that it’s their fault that a sale could not be made, when in reality the change was unsaleable under the current incentives.

Priorities only change when the reason we can’t change becomes the reason we have to in order to reach our intention.

Below are three examples from my past work through the lens of this framing:

| Reason they “couldn’t” change | Reason they had to change |

| Multiple start-ups merging caused language issues to arise but the differences of language were so baked into the products they were hard to change … | … until they had to translate everything into multiple languages created a need to simplify their approach to language so it could be reasonably translated |

| A billion-dollar eCommerce site exists for years without a mobile category navigation because the design system hasn’t yet tackled the bear that is the many versions of the navigation that currently exist … | … until we found out that the lack of navigation majorly impacted search engine optimization. |

| A restaurant chain went for years on a menu system they admitted was cumbersome and confusing because it would be too hard to align all the franchise owners to agree on a redesign … | … until certain states implemented requirements for nutritional information to be added to the menus and they had to be redesigned to accommodate. |

In all three cases I was the one called in when the “… until they” moment finally went down. Incentives had already shifted at that point in favor of making sense of the mess in all three cases. Before each of those moments, I could name any number of smart and capable people who had made the case for that same change and been told that the organization just couldn’t change.

“What do you do if you see messes all over and incentives aren’t ever aligned to fix them?“

At this juncture I feel the need to warn you that people have quit their jobs after five minutes with me on this subject. I quit my last job because of the reason I am about to lay out here. So read the rest of this with that as a warning. You might not like the answers to the questions I am about to ask.

Developing an Incentive Architecture

If you manage someone who is square in the middle of an environment surrounded by messes that people seem to be aware of but unwilling to make sense of, you need to help develop an incentive architecture before anyone can successfully propose changes to an information architecture.

Incentive architecture is a structured way to think about how and by what measures people you work with make decisions, and what that means for reaching your own intentions.

In 2017 I started working for Etsy as their first information architect. I had worked for them for the six months prior as a consultant making an outsider’s assessment of their information architecture. One of the first things I did as a full timer was convert my consulting findings into a list I called “Abby’s IA Hit List”

No one but my manager ever saw it, but it was where I kept notes about what I wanted to change, because “reasons”

My various “reasons” included:

- Documented knowledge of the impact to the business over time

- Findings from user centered research and analysis

- Lost opportunity to implement industry standards

- Personal persnicketiness and perfectionism (more on this at my Makesensemess talk this year)

With that list I had stated my own intentions for myself, and expressed them to my management. But that alone a project plan did not make. In the almost five years after that 10+ item list was written I had tackled maybe 5. I had checked off one item from my hitlist per year on average.

Now, I don’t want you leaving this story thinking I was able to then write my own ticket to fix what I wanted. None of those messes took even close to a full year to fix, and by my count I helped make sense of at least a few dozen other critical messes at Etsy during my tenure.

The trick was that I wasn’t focusing on checking off my list, I was focusing on helping wherever the business most needed at the time.

Some of my projects were tiny, like the time I helped sort out the seller location filter in search results. Other times it was larger efforts, like the new navigation approach for the entire marketplace Jenny Benevento and I co-developed in 2018.

The projects I actually saw through to completion happened because I attached my cart to a horse who wanted a cart. Simple as that.

To start to figure out your own incentive architecture, ask yourself the following line of questioning:

- What are you incentivized by?

- What decisions do you own or influence through that incentive?

- What are each of your stakeholders incentivized by?

- What decisions do they own or influence through that incentive?

- What incentives would the change you want take to happen?

- Do you have the power to make the change yourself?

- Do you have the power to change anyone else’s incentive?

- Do any of your stakeholders have aligned incentives?

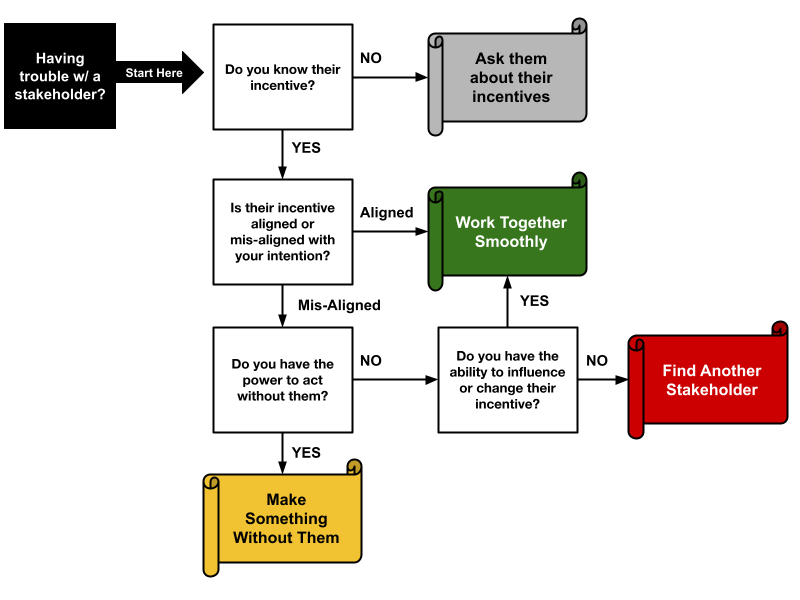

As you start to integrate this way of thinking into your work, I diagrammed out a flow I hope is a helpful reminder for any time someone is struggling with a stakeholder.

We can only work smoothly when incentives are aligned.

It might seem like an over-simplification but I am sincere when I tell you that in my experience the majority of drama, and bad vibes on projects and in organizations regardless of the medium, technology or organization type comes down to mis-aligned or un-identified differences of incentive.

In my experience there are generally three approaches you can take when you feel the signs of a weak incentives architecture:

- Ask About Incentives – Sometimes we have to have an honest conversation about how stakeholders think about and make decisions based on what they are incentivized by. With this new context for our stakeholder audience we will be better able to de-personalize their lack of support for our intentions and see how this or future intentions might be better aligned to gain their support

- Find Another Stakeholder – Sometimes we have done what we can do in terms of understanding, and the stakeholder we are trying to work with just can’t align within their current incentive architecture. This is the time to find someone else who might be a better fit. If you feel like you have exhausted all other stakeholders then you have reached what I call the “back-burner” point. This is the moment where you can safely put your intention on the backburner in hopes to re-engage on the effort when the incentives feel more aligned to be successful in working together or when you have the power to get it done without them.

- Make Something Without Them – Sometimes by doing this incentive investigatory work we figure out we actually don’t need a certain stakeholder to get something done, we were just being polite. If we have enough power and can move past pleasing people and pursue our own intentions without fixing what is misaligned – we should do just that.

Incentive architecture is management work.

You might notice that I started this article talking to managers, and reiterated that point again mid way through. Now to close this article I want to get out the big hammer. I am going to use this moment to be blunt, because your direct reports might not be able to be. Because, power.

If a project has already been staffed before you are sure incentives are aligned for your people to be successful, you are not doing your job.

If you are not taking on (at the very least) a support role in these conversations with your direct report’s stakeholders you are not setting up your team for success.

If you have a manager who needs to practice incentive architecture so you can do your job, slip them this article or post it to a company slack with enough clickbait to get attention.

I suggest something like:

One simple thing makes teams more effective and can reduce interpersonal drama, you won’t believe what it is: www.abbycovert.com/writing/incentive-architecture

–

If you enjoyed my thoughts on this topic you might also enjoy reading these other related articles:

- Marketing Campaigns Fail When IA is Ignored

- Structural Arguments for Information Architecture

- What is the return on investing in information architecture?

If you are ready to go from curious to confidently practicing information architecture in your own context, consider becoming one of my students by registering for The Practitioner’s Guide to How to Make Sense of Any Mess. This course includes access to my LIVE monthly office hours. If you want to keep up with the latest from me, join my monthly email list. And if you found this to be of value, I would be so appreciative if you sent this piece to anyone else who might also find value in it.

If you have a team looking to level-up their information architecture skills, I have a catalog of remote, longform courses and workshops for teams who want to improve IA as a core collaborative skill.