The IA Element of Everything

The following is a transcript and selected visuals from a keynote given at World IA Day in Cambridge, MA, USA in February 2020.

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to celebrate the union of information and architecture.

Information with its particularities and nuances, messy and human. Architecture with its strength of structure and dependable steadfastness. An unlikely match to some perhaps, but anyone who has spent some quality time with these two will tell you a different story. Only when you start to understand how these two work together to create a whole that is far greater than the sum of its parts will you “get it”

Have you ever had a really tough time understanding something until someone broke it down into its pieces or related it to another thing that you understand already? Maybe a concept in school, maybe a hard problem at work, maybe a skill you have been trying to master. We have all had that moment, when we encounter the right information in the right arrangement that it just clicks and we “get it” — light bulbs, fireworks, epiphanies.

Have you ever been working on a hard problem with other people, and no matter how many times you talk it through you end up spun around and upside down, all wrapped up in the tentacles of complexity? Until that moment when some brave soul starts to draw it out on a napkin or a whiteboard while everyone else stays fearfully in a well distanced semicircle observing this vulnerable act of sense making. And then like magic one by one, their shoulders lax and their out-stretched fingers draw them nearer and nearer to the center, as the building blocks of direction start to arrange themselves and the mortar of agreement starts to bring the group together.

This is the power of information architecture. IA can give the greatest gifts of all gifts: Clarity, Direction and Agreement.

So here we are, almost 50 years after the words information and architecture met and fell madly in love. 25 years into the field of information architecture meeting as a community regularly to discuss itself. 8 years into this wonderful event celebrating Information Architecture in local communities.

And what do we have to show for it:

- A decline in jobs with information architecture explicitly within the outlined responsibilities

- The elimination of IA specialists from many organizations

- The creation of UX and design programs that don’t teach the skills of IA or have reduced them to a lecture on making sitemaps

- A job market telling young IAs to generalize into UX design or perish in academia or consulting.

We have more sense makers now than ever before, yet they are being told that their skills are only narrowly applicable to one type of work: user experience design

Now it would be easy to be more than disheartened by the reality that I see before us. In fact, if I were a pessimist and saw these clues as signals of our future, I might come to the easy conclusion that we are seeing the end of information architecture.

Lucky for the direction this talk is about to take, I am ever the optimist and see these as clues to a clearer future. Because ultimately I see each of these as an information architecture challenge in front of our community.

I see these as strong signals for where we need to put our collective efforts.

- We need to show the world how important a concept information architecture is by showing them examples of it in their real lives – good and bad.

- We need to teach people to be able to point to certain problems in their lives and confidently describe them as information architecture problems, regardless of their role or interest in fixing those problems.

- We need to continually iterate on how IA is taught and to whom, and specifically how it is positioned by those teaching within adjacent and related disciplines.

- We need information architecture to be accessible to the masses as a term that accurately describes a part of the human condition

I dream of a world where information architecture is like physics in terms of how it is treated in common vernacular. Physics is a concept that everyone can relate in simple ways to their lives. Yet most people don’t understand the concept at any kind of depth. BUT it is generally understood when physics is to blame for something in real life.

When my toddler son drops a rubber ball and it bounces wildly around the room, and my four year old niece asks why it bounces so uncontrollably, physics is to blame. She won’t understand physics for a good long while, or perhaps ever if she is like me, yet it is strangely comforting to know the word for what is impacting the world around her.

Well – when a voter votes an unintended way on an issue because of the confusing structure or language of the ballot, that’s a failure of information architecture. When the form a caucus leader is asked to use to report results doesnt make sense to them, and therefore the data is entered wrongly or not at all, that’s a failure of information architecture. Today, if you asked that voter or that caucus leader: what went wrong? The highest likelihood is that person would not be able to point to the issue and give it a name. Even worse, the people in charge of these processes also likely dont have the name for this problem, and therefore cannot look for the right kind of help.

Watching Iowa struggle to not have a name for IA was a particularly meta moment for me recently, I am guessing I am not alone. Everyone in the media was so quick to say it was a failure of training, or a failure of math… but all a skilled information architect has to do is get one look at that form to know the truth. IA is a big part of what failed in Iowa.

Now – I like the comparison to physics because information architecture is another concept where the label was given to it far after the concept itself was having an impact on the human experience.

Apples were falling from trees far before Aristotle decided to label the field that explained why. Similarly humans have been creating, navigating and advancing information architectures for as long as we have been creating information that needed structure to be understandable to others.

I want to be clear. As clear as I can be. I don’t think that information architecture will ever go away. I think the idea of structuring information for other people is a life skill that everyone benefits from every day. I believe that everywhere there is information, there is architecture responsible for delivering that information. Put simply: I believe information architecture is in everything.

So with that framing, why would it matter if the terms information architecture continued to go unspoken by the masses? Why would it matter if no one other that self proclaimed information architects know the label for the thing everyone is going around doing for themselves and others all day, everyday? Why do the words information architecture even matter at all?

Well let’s go back to our physics example. What if there was no common term to describe that set of principles and phenomenon that dictate so much of the world around us? It’s a ridiculous question to dwell on for very long isn’t it? Because this all important concept cannot go unnamed now that it is recognizable and apparent to all, even those who do not seek to understand it.

It is my greatest hope that information architecture can be on path for that same recognizable reality. Because IA is an antidote to the part of the human condition that is fraught with complexity and needs tools for making sense. Even more important is the recognition that the need for information architecture is increasing everyday, as the world creates seemingly insurmountable mounds of information every second.

In confronting my feels on IA’s decline into potential obscurity, I had an important realization. This is a classic information architecture problem to solve.

What if you had an IA assignment that went something like this: You have a product that you know would be so useful to so many people, yet only people from a certain background and educational path are likely to know about this product at all. With this as our assignment our first step as IAs might be to identify types of people or types of work where IA work is being done now but under no name or a different name. By making this list we could start to think of language and structures for teaching these types of users about our product.

So I want to spend this time I have with you today talking about places where IA is being practiced all around us.

But first I have an important question: How many of you own a microwave?

Keep your hand up if you know the wattage of your microwave.

A few weeks back I found myself in an everyday IA conundrum that I think are all too common in daily life. My mother-in-law was making dinner and I overheard her ask my father in law about how many watts the microwave is. My father in law responded “1500!” to which she responded “No, no that can’t be, it only goes up to 1200!” to which my father in law exclaims “it probably doesn’t even matter!”

Now at this point I am intrigued. I was in the process of writing this talk and this sounded like one of those moments to me. One of those little bits of friction in everyday life because of an IA choice that someone made.

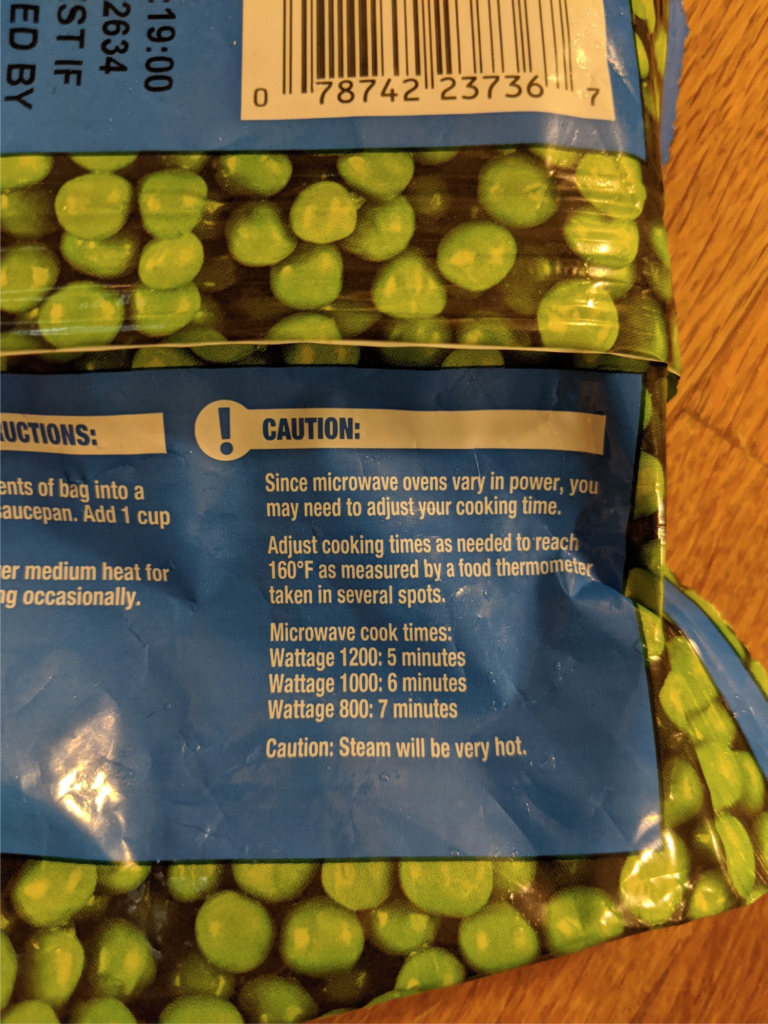

So I inquired about what was going on. It turns out that she was attempting to heat up some frozen peas and the instructions varied pretty wildy on how much time you should cook them based on the wattage of the microwave.

The range was only from 800-1200 watts but the spread of options for cooking time was 2 minutes, an absolute eternity in microwave time. To make matters worse, the alternative they have provided to knowing your wattage is to use a food thermometer! I mean for real? Now take a second to imagine myself and my mother in law delicately poking peas with a food thermometer “in several spots”

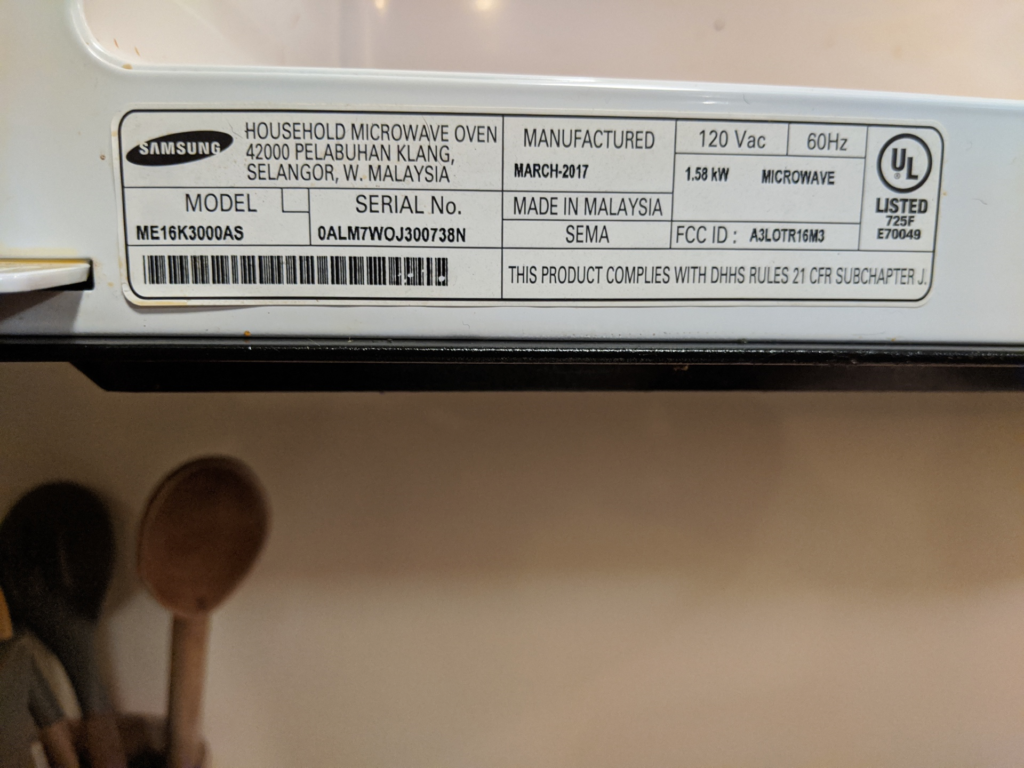

So at this point, I started to really get into figuring this out so I said, “hmm, the wattage is probably noted on the sticker inside the microwave, right?” — so we looked and guess what?

No wattage! But BUT buuuuttt… We see a measurement of 60 hertz.

So I say the next logical thing for an elder millenial to say to her boomer mother in law: Let’s just ask Google to convert wattage to hertz!

Ok audience, how many of you think Google was able to do that?

Womp womp. No dice. It turns out that hertz and wattage are like apples and oranges and cannot be converted from one to the other.

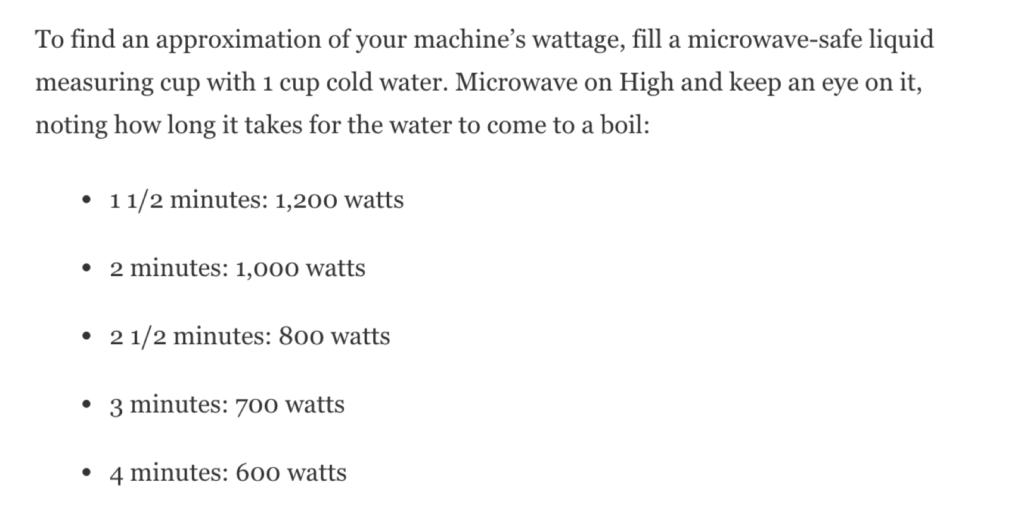

Now in looking into this issue, I have found that it is not just us. This is a fairly well known concern of microwave cooks the world over.

In fact, blogs like Epicurious offer a mister wizard style exercise for figuring out what your microwave wattage is in the all too likely case that the sticker on the inside doesn’t have wattage marked.

You didn’t think I’d leave you hanging on figuring out your microwave wattage, did you?

So surely inquiring minds want to know how many minutes we landed on for the peas? We made the decision to try 6 min because it was right in the middle of the scale of cooking times. What could go wrong?

Ok audience, who thinks the peas were

Under cooked?

Overcooked?

Just Right?

The overcooks win. These peas were WAY over done. And to be honest, this is the moment my mind was blown. How can wattage matter so much, yet be presented in such an unclear way. It’s almost like the makers of these peas have zero concern for whether we will successfully heat up their product.

We assumed that the microwave was in the middle of the scale because we also assumed that the scale presented was the entire scale, it’s not. I have since confirmed that microwaves go up to 2200 watts. The idea that 6 minutes could equal SUCH an overcooked result was deeply concerning. So now we are eating peas that are WAY over done and wondering how this microwave is actually at the highest end of the microwave spectrum. And more importantly: we are feeling really stupid. We are two grown women unable to heat peas in a microwave in this year of the lord 2020. Shouldn’t we have this figured out by now?

This is one of those everyday problems that stems from a few issues commonly seen in information architecture, and hey if we are going to be like physics, lets get some names for these things we see happen over and over again:

Unnecessary exactitude. Rounding off is not a sin. Not only is extreme accuracy not always information, it is often not necessary.”

Richard Saul Wurman

The main problem that we are observing in this scenario is what Richard Saul Wurman termed “unnecessary exactitude” — the microwave watts are a detail that anyone who has spent a modicum of time with microwaves or users of microwaves would realize is fraught with concern and lack of clarity. BUT something else they would learn is that it turns out that watts really are very much related to the size and type of microwave that you have. There is also a fairly small range of microwaves in typical homes these days.

So it is unnecessary to say 800 or 1200 watts when you could say “Small Countertop Microwave” or “Large Installed Microwave” which would be much more relatable to the typical microwave cook.

So why does this even matter? If I hadn’t gotten involved in the whole scene, who is to say whether my mother in law would even remember this incident a few hours or days later.

But here we are weeks later. And as Pema Chodron would likely point out I have been totally “hooked” by this. I am haunted by its significant insignificance.

I hate that we face moments like this all day everyday. Moments where a little bit of IA thought from the makers of things would go a long way to help us feel confident and in control of our own destinies.

If you spend enough time with users you will hear how often they blame themselves for “not understanding” — and unfortunately in everyday life we don’t have a moderator to remind us that it is the job of the product to make sense, not the job of the user to get it.

This moment made me start to really dwell on an important question: What’s the collective impact of all these tiny moments of frustration with oneself? And more importantly, whose problem is this to solve? Walmart’s? Samsung’s? Or does this issue perhaps exist purely because it exists in that all to common messy middle where IA problems crop up.

There is all this friction in the seemingly innocuous tasks of our day, and honestly as users there is little or nothing we can do about it. My mother in law doesnt shop for frozen peas by whose directions respect her mental model the most, and she doesn’t buy microwave ovens based on whether they have a clear way to communicate wattage.

My point is that people can’t ask for things to get better when they don’t know how to even describe the thing that they struggle with. As soon as I pointed out that the failure was of the person who architected the information on the bag, not her, she got it – and more importantly, she was rightfully pissed off.

Her response was:

Well Walmart needs better information architects!

See how easy that is.

Give people the words for the things they experience and we empower them to demand things improve. If nothing else, now when her peas are overdone, she can blame Walmart packaging designers not herself for not understanding microwave wattage.

So you might be thinking, this is small potatoes right, I mean it was actually small peas, but stay with me. Look – I am not here to shame the pea packaging designer for their poor IA choices, although Walmart I think you have the resources to have done better here. I am not planning to waste this opportunity that I have to speak with you today on pointing out petty IA failures. So let’s jump to a biggie. Because I don’t know about you, but every time I encounter the media these days I hear information architecture headlines all over the place. And there is one area where the implications of IA decisions have high stakes on the fabric of our society.

It strikes me how often a two party system is fighting over ontology. It’s amazing how many multi decade arguments are disagreements surrounding taxonomy. And I doubt I am alone in thinking that the masterful choreography of information delivery being employed by bots, and extreme leaning media moguls would be inspiring if it weren’t so down-right terrifying.

So here is our next stop on this journey: Political Ideology

My hope is that this part of my talk can be delivered without bias, in a timeframe where this topic is particularly fraught with divisive commentary. But when I look out into the world and see where IA is being practiced but without that name, I thought first to political ideology.

Specifically the journey that academic and research terms take on their way to being in the hands of the spin doctors working to craft the perfect way for the information to be consumed by the masses.

Did you know if something rhymes, people are more likely to believe it? Alliteration is another way to make something seem more trustworthy. Did you know that if you share something untrue, and then immediately send a retraction, people will still believe the original thing more often than have consumed the retraction. Did you know that there are people out there making websites for fake local news organizations because they know that headlines seen through brands like that feel more authentic, even if its not from your town or even a town you’ve ever heard of.

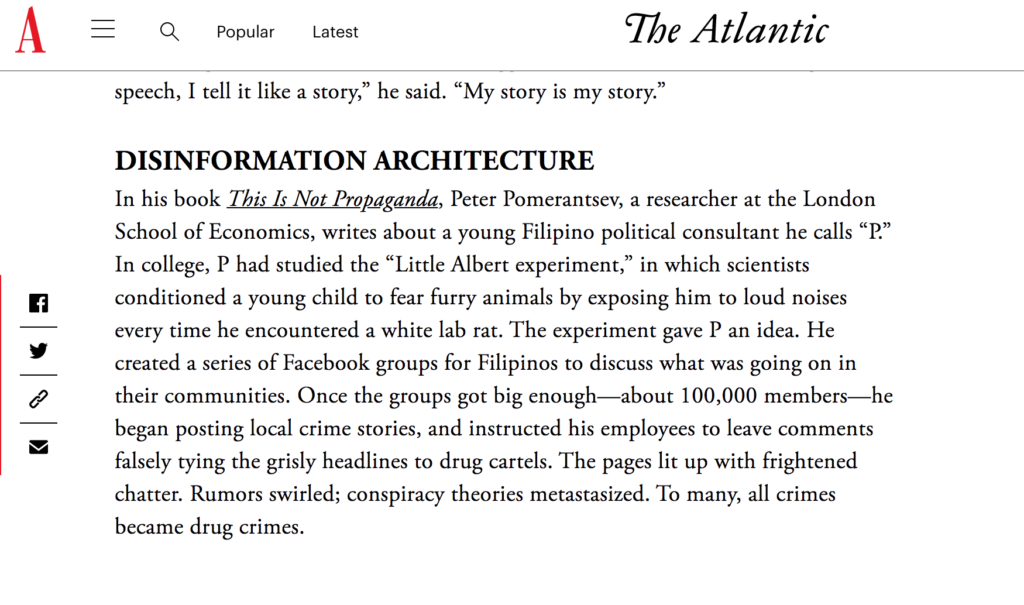

These are all the tricks of the trade when it comes to propaganda. And you know what good propaganda has, excellent information architecture.

Or as the Atlantic recently wrote, “disinformation architecture”

So let’s take a look at one of these ontological war stories to see what happened with an especially fraught term: Global Warming

Over the last 50 years, there has been a slow ontological shift around the language that we collectively use to talk about our sustained impact on the world around us. On the way we have experienced everything from dinner table squabbles to knock down drag out policy disagreements. And the stake for agreement is fairly high: the timeline on which the human species might be pushed out of our comfort level living on this planet.

In the 1970s, there was a different term used primarily for the study of human impact on the climate, it was called “inadvertent climate modification” — sexy eh? An article by Nasa entitled “What’s in a name?” described the term as “while clunky and dull, an accurate reflection of the state of knowledge.”

At this point in time many scientists accepted that human activities could cause climate change, but they did not know which direction that change might take. Industrial emissions of tiny airborne particles called aerosols might cause cooling, while greenhouse gas emissions could cause warming. It was a standoff that needed more research and time to determine what was really going on.

The term “Global Warming’ saw its first use in a 1975 article by geochemist Wallace Broecker of Columbia University titled “Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?”

Later in 1979 a study was published by Jule Charney of MIT for the National Academy of Science on carbon dioxide’s impact on climate. It indicated that the temperature of the earth’s surface was indeed increasing.

In the Charney Report, when referring to surface temperature change, Charney used Broeckers term “global warming” but when discussing the many other changes that might be experienced by increasing carbon dioxide, Charney used “climate change.”

So now there was not one but two terms to teach to the public: one whose purpose was to indicate the climate is changing based on our actions, the other to communicate that we now have significant proof that the surface temperature of the earth is increasing.

During the late 1980s one more term entered the lexicon, “global change.” This term was meant to encompass many other kinds of change in addition to climate change that might result from the rising surface temperature of the earth. This term was approved and made part of the official controlled vocabulary of researchers working in this space – but not until 1989.

Now before it could take hold as the primary term as scientists intended, “global warming” became the dominant popular term in June 1988, when NASA scientist James E. Hansen testified to Congress about climate, specifically referring to global warming.

So this is fascinating to me. This is a story of information architecture. This is a story about the slow and deliberate establishment of a controlled vocabulary. But it is also a story about the all too common instance when a controlled vocabulary is ignored by users because the nuance is lost on them, or because the approach doesn’t make sense in terms of their experience of the problem space.

Honest question: How many of you have dealt with this reality when establishing a controlled vocabulary at your job? I mean I once had to go as far as to wear a gym whistle to blow into whenever a particular client accidentally slipped up in using a retired term in meetings for months after our controlled vocabulary was “finalized.”

The truth is that the public doesn’t care about using the right term and nor should they – that simply is not their job. They are rightfully worried about bigger things than semantics. Like their children growing up in a world that is increasingly pushing back against decades of our collective lack of care.

So what’s so bad about getting this term wrong? It’s just semantics, right?

Well it turns out that in this specific case, the scientific swirl around establishing these terms is being singled out as a proof point for dissent. It’s the crack in the information architecture about this subject that propagandists have identified as a weakness of clarity to exploit. Because they know that the lack of information creates information and that a decade is a long time to not have agreed-to words for a concept with so much importance. And because they know that if they point out the seeming lack of clarity from even 30+ years ago, they can create public disillusionment towards the scientific community.

All you have to do is get into a simple conversation with any self proclaimed “climate change denier” to realize that this seemingly tiny slip of ontological dissemination contributed so majorly to the sharknado of misinformation swirling around this all important subject. I will never forget the first time a climate denier family member of mine argued so emphatically about the fact that they still didn’t even know if the earth was warming or cooling, so global warming is not to be believed. There was seemingly no way to convince them otherwise, we have since agreed to not discuss this but I will say the idea of what his facebook feed looks like or his targeting google ads are absolutely terrifies me – because we now not only have access to all information at our fingertips, we also have the ability to micro target people based on incredibly creepy amounts of profiling data about them.

The effects of this are being studied in many contexts, many closely resembling the work I have done as an information architect to understand the various impacts of different labels on a user’s experience.

So the important question for the IA community is: is this result attributable to a failure of information architecture? Or are we comfortable with the idea that this divisiveness is actually a success of information architecture?

Could it be that the propaganda machines of the radicalized parts of our political systems exploited the wishy washy lack of a widely accepted controlled vocabulary as an inroad to take a well researched topic and for a lack of a better term: throw shade.

This matters. This is real. IA is everywhere. There is an IA element to everything. Our brains, our culture, our whole freaking world is being shaped by these seemingly small information architecture decisions made by just a few people and understood by fewer still.

If this issue which is currently so top of mind is not a significant enough example to remind us that language matters, I don’t know what could.

In writing this talk, I questioned including this example for the shear reason of its controversial and hard to talk about. But in the end I couldn’t ignore it. It’s not only an almost perfect lesson that information can be created by the lack (or in this case swirl) of information it’s perhaps a needed reminder that IA can be practiced to help people but it can also be practiced to manipulate people.

We’ve talked about a lot today, from frozen peas to melting icebergs. I hope you are walking away from this talk with permission to make information architecture bigger. Permission to see IA all around you. Permission to point at examples of IA and teach your children about its successes and failures in the world around them. Permission to hear about IA problems in your local community and talk about them as IA problems.

I think we have spent far too many years snickering about bad restaurant menu IA and poor form designs and not enough time getting this important information into the hands of the right people. The people who make the things that real people interact with all day everyday.

Do we really want to look back on this community in ten years and realize that we made IA into something only billion dollar companies could make practical use of?

I don’t want to wake up to that future, and I hope neither do you. But that is where we are headed friends. Unless we pull up and look around at the opportunity in front of us.

Information architecture is a part of the human experience, whether anyone is paying attention to it or not. We are the people who get to decide happens next.

Your move.