10 Information Architecture Lessons for Teachers

In 2012 I started teaching information architecture as an elective for undergraduates at Parsons, a well-known arts and fashion college in the heart of downtown Manhattan. This was by all accounts an actual dream job for me.

When I graduated from undergraduate myself in 2004 I was convinced I would someday, somehow end up back in art school – but as a teacher this time around.

The first semester was a whirlwind and I learned a whole lot about teaching, about being in an art school but as faculty, and most importantly about teaching information architecture.

My class was art school kids of a wide range of artistic intentions. I had students from fashion design, digital design, architecture, and film that first semester. Each came to my course from a different program yet you would have thought they were all in the same program based on how applicable information architecture was to each of their individual pursuits.

Information architecture (IA) is the way we arrange the parts to make sense as a whole.

When defined broadly, as it is above, writing an article to teach my fellow teachers about IA feels almost silly. But I have learned from practicing information architecture and teaching it to others that most people practicing information architecture are doing so while completely unaware of the term for the skillset they are executing on.

While not knowing the term for what you are doing might be ok in the short term, in my opinion it can hinder us in the long term by limiting the terminology we can use when seeking advice to improve on that part of our skillset. If we aren’t careful critical IA lessons can get lost in a sea of advice about “visual thinking” “communication” “organization” and “soft-skills”

Outside of design and tech, teachers are the profession I am the most convinced that information architecture is a part of everyday expectations – they are also the group of people most responsible for how future generations learn how to make sense.

In this article I have ten bite-sized lessons for teachers about applying information architecture to their own work. I also included a not so secret agenda throughout to help in making sure that more modern day students learn the timeless art of sensemaking.

#1 Information is not the same as content

Information is whatever is being perceived by our audience. In the case of teachers that means we can’t just transfer our lesson content to our students, we can only present it in a way that we hope is interpreted the way we intend.

Not only is this a good lesson to remind teachers of, it’s also the number one from this list that I wish all adults would help teach to children. And hey, let’s teach other adults for that matter. There are plenty for whom this lesson is entirely new, and many more for whom a reminder is quite likely desperately needed.

#2 There are meaningful differences between the why, what and how of any undertaking

Why, what and how are important questions to break down about whatever it is you are doing. When we overly focus on one or two of these questions, and leave the rest up to chance we often see negative returns on that lack of investment. As a teacher make sure you are answering all three questions about the material you are presenting in your classroom:

- Intention: Why are you teaching __________?

- Scope: What are you including/not including to reach that intention?

- Audience: How will students integrate this new knowledge into their work or life?

Balancing these three questions is a thoughtful process any maker must undertake, and many teachers also guide students through.

#3 Stakeholders, users and makers are critical to understand in making things that make sense

Teachers manage an information ecosystem made up of students, parents, administrators, and peers among others. As the maker in this formula, teachers need to make their decisions with their students and stakeholders in mind. But they also need to bring their own lens to the intention if they want to feel connected to the material or the outcomes. Information architecture is best executed from the intersection of three ideals:

- Stakeholder Intention

- Audience Usability

- Maker Intention

It is the balance of priorities between these three audiences that ultimately determine the scope of your work as a teacher as well as what kind of impact you can have on your students.

#4 The world is made of taxonomies

Taxonomy is the classification of something, usually for a specific purpose. Classification is the rules we establish for sorting things into a taxonomy. Whether it is the classification by which you have divided your lessons across a semester, or the ways in which you have decided to arrange your classroom or organize your class library – taxonomies are all around you.

In early childhood, we learn about groups like shapes, colors, animals and everyday objects – this is starting our foundational education around one of the most fundamental human tools: taxonomy.

During childhood we also start to become more aware of the subjectivity of the world around us, and our own role in weaving subjective webs of information in the minds of other people.

Many of the world’s atrocities have been brought on by taxonomies powered by opaque classification, take for example the introduction of the phrase “algorithmic cruelty” to describe all the times when people take the brunt of not being classified by machines thoughtfully.

An important lesson for teachers is to make this lesson more explicit, as it creates a basis for information literacy to improve. If the world is made of taxonomies, always be asking (and encouraging students to ask) how something is classified to appear in its current placement in a taxonomy.

#5 Ontology is the declaration of meaning

Language is not static. It is a dynamic, moveable force attached inextricably to the human experience. There is a term for when we collect all the known meanings of the language we collectively use.

Lexicography is the collection of meaning.

There is another term meant to explore the subjectivity of using language to describe and interact with the world around us. This is how we describe the act of deciding what something ought to mean in a specific context.

Ontology is the declaration of meaning.

From the catholic church deciding to reclassify capybara, beavers and alligators as fish for the purpose of eating them during certain holy days, to the supreme transformation the word “like” has taken becoming integral to digital platforms – ontological decisions command everything from consistency to oeuvre in the world around us.

A simple ontological discussion to have with your students at pretty much any level of education is about whether tomatoes are a fruit or vegetable.

In terms of scientific classification, some students might know that tomatoes are fruit. But inevitably in my experience for many students this might be new information since tomatoes seem to be treated as a ‘vegetable’.

This leads to an ah-ha moment that tomatoes are not alone in this ontological conundrum! There is actually a rather robust “fruit masquerading as vegetable” genre. Squash, olives, cucumbers, avocados, eggplant, peppers, and okra are also fruits that are commonly mistaken as vegetables.

Pause. Do you want to hear the saddest ontological breakdown story a student ever told me?

This student brought a fruit to school to share with her class in kindergarten. She was so proud to bring her family’s home grown tomato. But upon further understanding of the context, she realized all too late that the assignment was to contribute to a community fruit salad, of which no one (including her) thought her tomato belonged.

This is a great example of ontological breakdown in action, as well as a good reminder that we need to be on the lookout for places where we are introducing ambiguity based on the words we chose and the context we share.

The slippery nature of language is worth pausing on with ourselves when teaching but also worth breaking down for our students, especially if we have responsibility for teaching them to be better communicators.

#6 Controlling your vocabulary improves retention and clarity

The best piece of advice I ever received when it comes to practicing information architecture is:

“Always know what you mean, when you say what you say” – Dan Klyn

When we prepare materials to teach other people, we have to heed this warning double. In my experience controlling the vocabulary in a classroom helps alleviate anxiety, improve retention and enhances clarity of the material.

Putting this lesson into practice as a teacher often means consolidating and differentiating synonyms. Sometimes we can collect too many words that to our students mean the same thing. Other times we have a difference of meaning in mind, but the terms chosen are too similar to get that across to students without explicit instruction.

- Consolidation: Are there multiple unneeded terms describing the same thing?

- Differentiation: Are there words that are meant to mean different things but have become accidental synonyms?

When I did some information architecture work for the sales team at Nike, one of the differentiation initiatives I worked on was to fix the accidental synonym that kept happening with the words customer and consumer. They were meant to mean two different types of users for the team, but they were so close in pronunciation and spelling that they couldn’t be easily differentiated enough to be clear.

This led to them being used wrongly more often than was comfortable. It also caused a lot of anxiety for new people who had a hard time keeping it straight. We rallied around changing “customer” to “retailer” and there was an almost immediate increase in clarity.

#7 Diagrams allow us to explore further than in our head alone

I am not going to fool myself into thinking that I am telling any teacher for the first time how important visuals are when teaching. I am however bold enough to know that not enough teachers have learned the basics about how to make visual representations that help their students.

Diagrams are visual representations that help someone. And by that definition most frameworks, maps, charts and graphs that one might use in the classroom are diagrams. The power of diagrams comes down to a core tenet of information architecture: Things are always easier to explore when made into objects of discourse.

Teachers, like many other diagram heavy professions, are never taught to diagram themselves or what it means to make a diagram that’s any good. This perturbed me enough to write a book, and an eCourse to help rid the world of bad diagrams, one diagrammer at a time.

#8 Contexts and channels are critical to understand when making things that make sense

If ever an information architecture lesson came to the front stage for teachers it was the impact of the change of context and channel on our teaching when we all experienced stay at home orders around Covid-19 and the world’s teachers were suddenly expected to educate everyone online.

The contexts and channels in which content is presented matters greatly to the information that is left behind in the mind of our audience.

Teachers can implement this lesson by asking important questions about the impact of other contexts and channels within and outside the classroom:

- Channel: How does each channel you use to communicate with students align (or misalign) with the intention for your teaching work?

- Context: Under what context shifts might your lessons change or be more difficult for students to relate to, apply to their reality or retain for later?

By understanding the impact that channel and context can have on our ability to make sense to our students, we can better assure our hard work is not getting lost in the cracks of context switching or channel changing.

#9 Defining measurement is essential to defining “good”

This is probably the hardest lesson to teach to students. I think that’s because they expect that much more of the world is figured out than it actually is.

When we do any sort of qualitative assessment, we have to be careful when using terms like “good” or even “correct” in some cases. The reason for this is because without further measurement, adjectives like these often fail to give a clear explanation of why something is (or is not) reaching a goal.

As teachers this means clearly defining the way things will be graded, the ideal qualities of finished work as well as the weighting of those qualities to get to a final rubric for measuring student work. The transparency with which you do this can dramatically change student perception, as well as behavior.

I also secretly hope this lesson sneaks into conversations about future career and education choices. I find a whole lot of should storms happening in the minds of many students around what would be the next “good” thing to do.

Being invited to think about the definition of that idea in terms of their own priorities and measurements for their own quality of output is a life changing lesson I have had the pleasure to teach many students while teaching them about IA.

#10 Sensemaking is full of an inherent emotional turmoil

As teachers we are often the trusted someones who are turned to when that emotional turmoil starts to get unbearable for a student.

I left this doozy for last, because … well … doozy! One of the hardest lessons to impart on people about information architecture is the emotional turmoil the sensemaking process can bring about.

The bad news is I can’t solve this problem in a way that leaves you without teary-eyed students in your doorway, or inbox.

The good news is many of the tools of information architecture are just what these teary-eyed students need to confront the emotional part of making sense of whatever their current mess is.

Also I wrote a book about exactly that, and it’s available for you and your students for free online.

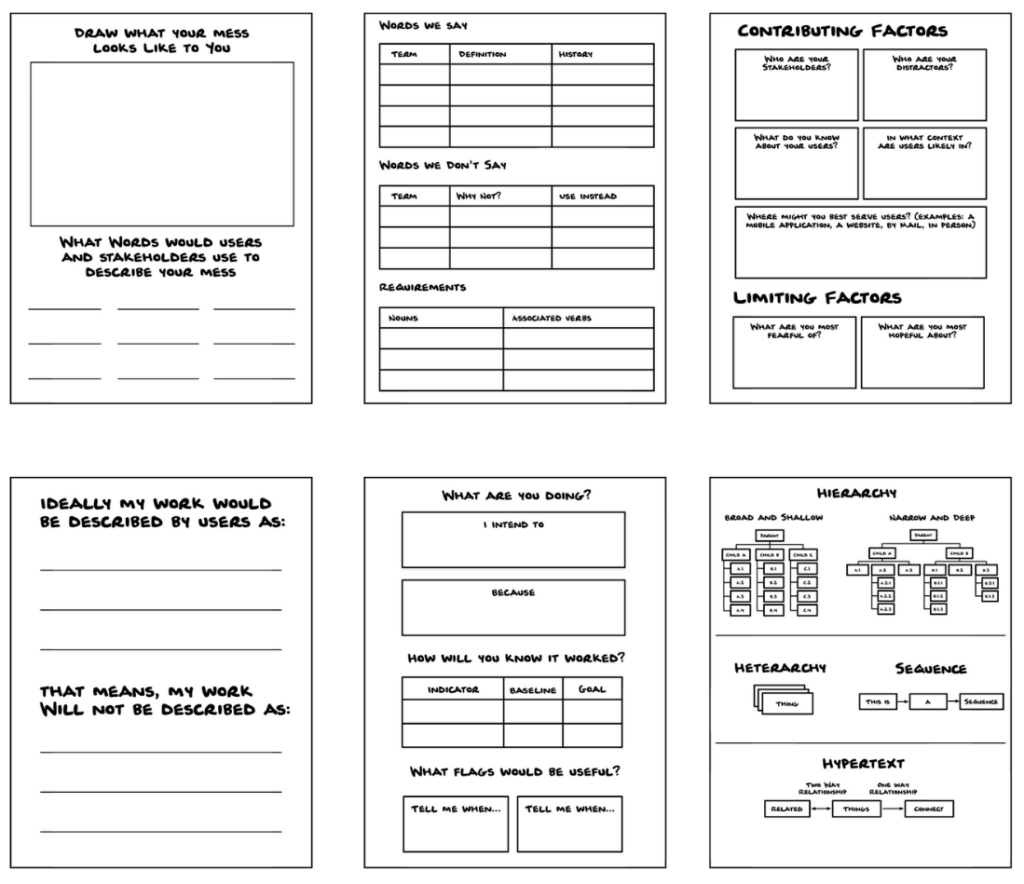

In How to Make Sense of Any Mess, I provide 6 worksheets for students – all of which are simple enough for most adult students to just dive into without any instruction at all.

The worksheets involve simple IA exercises that I often use to help people confront the feelings they have about their sensemaking work:

- Draw a Picture of Your Mess

- Choose Your Words

- Diagram Your Reality

- Choose a Direction

- Measure the Distance

- Play with Structure

When paired with hearing students vent while normalizing their emotions it is truly amazing to see the results of a simple taxonomic push or ontological question of my students.

Here are a few of my go-to favorite prompts with students reflecting IA principles:

- “Do you have a picture of what is in your head yet?”

- “When you say _______, what do you mean?”

- “When you say _______, do you mean the same thing as when you say _______?”

- “What do you know about the channels and context of your audience for this?

- “What are you using to measure your ability to reach your intention?”

I have consistently had students note direction-changing and even “life-changing” results from having been asked questions like the above.

If reading this article sparked your interest in learning more about information architecture for improvement of your own IA skill set, I hope you will consider spending less than 90 minutes reading How to Make Sense of Any Mess – which is available in its entirety for free online.

Do your students need to make more sense?

If you think some (or all) of the lessons from this article or from the book would be great for your students: check out The Teacher’s Guide to How to Make Sense of Any Mess.

I designed this collection of modular lessons, slides, activities, discussion prompts and assignments to be easily integrated into your existing course materials. This project was guided by a series of round table discussions with 30+ teachers who saw a clear need to teach information architecture to their students as a part of their existing courses.

In Closing

We all need to learn how to make more sense. Many teachers and practicing professionals agree that IA is a timeless skill that many modern students could use guidance in.

Whether you are teaching something that students need IA skills directly for or not, you are using your IA skills to reach students with your intended lessons everyday.

I hope this article gave you some starting places for improving where you are IA weak, as well as a reminder of the places where you are already IA strong.

If we teachers work on improving and making our IA strengths explicit as a model for our students to follow, imagine the clarity they could bring to this incredibly unclear world.

🤓 If you are ready to integrate IA into your lesson plan, check out The Teacher’s Guide to How to Make Sense of Any Mess. Includes access to my LIVE monthly meet-up of Teachers Who Make Sense.

✍️ If you enjoyed my thoughts on this topic you might also enjoy reading about what I learned about just how early we learn IA in early childhood.

📚 How to Make Sense of Any Mess is available in its entirety for free online, making it an accessible resource for all types of students.

💌 If you want to keep up with the latest from me, join my monthly email list. And if you found this to be of value, I would be so appreciative if you sent this piece to anyone else who might also find value in it.