How to Care for Any Sensemaker

I first began to turn to my information architecture skills to help me take better care of myself after I was hospitalized from burn-out in the days leading up World IA Day 2012. A friend held my hand as a doctor explained to me that I was too busy, and it was making me really, really sick.

That rock-bottom moment was a major wake-up call for me about how important taking care of myself is. It seemed that in order to make sense in service of other people I had to first take care of the sensemaker, and spoiler alert … that sensemaker was me.

One of the central tenets of information architecture is that when we are able to be thoughtful about our needs the systems that are within our control can be created or changed to serve our unique intentions.

I spent the first ten years of my career as an information architect applying this thinking to websites, mobile applications, museum exhibits, restaurant menus, graduate school programs, events, games, social media campaigns, books and more … all the while totally unaware I would spend the next ten years learning how those same information architecture skills would help when making sense of my own care system.

What is a Care System?

Your care system is whatever tools and systems you have in place to keep from losing yourself.

Whether you use apps, or a notebook, or scraps of paper all over your home (it me!), or have it all just swirling around in tiny tornados inside your brain (um… you ok?) somewhere you are making conscious and unconscious decisions and plans about areas of your own care like:

- Nourishment

- Rituals

- Movement

- Medical Adherence

- Mental Health

- Cleanliness

- Tasks & Errands

- Finances

- Availability for other humans

- Commitments with other humans

- Leisure

- Stress Management

- Other Care

When you look at the list above you might be thinking there are several areas where you are currently severely over- or under-invested and even perhaps in ways that impact your overall quality of life.

Some of us have strong, thoughtful care systems that treat us like the unique human beings we are. While many of us have a care system strung together in reflection of bad modeling or bad circumstances that treat us more like human givers. I had the latter, until I put my sensemaker mind on believing I deserve the former and knowing I had the skills to create a better system.

As a neurodivergent person who works mostly alone, and is prone to burn out, calendars and task tracking have been invaluable tools in my care system and have helped me to reach big goals.

Calendars

For as long as I can remember I have been obsessed with calendars as an organization device and with experimenting with integrating time and calendars into my life.

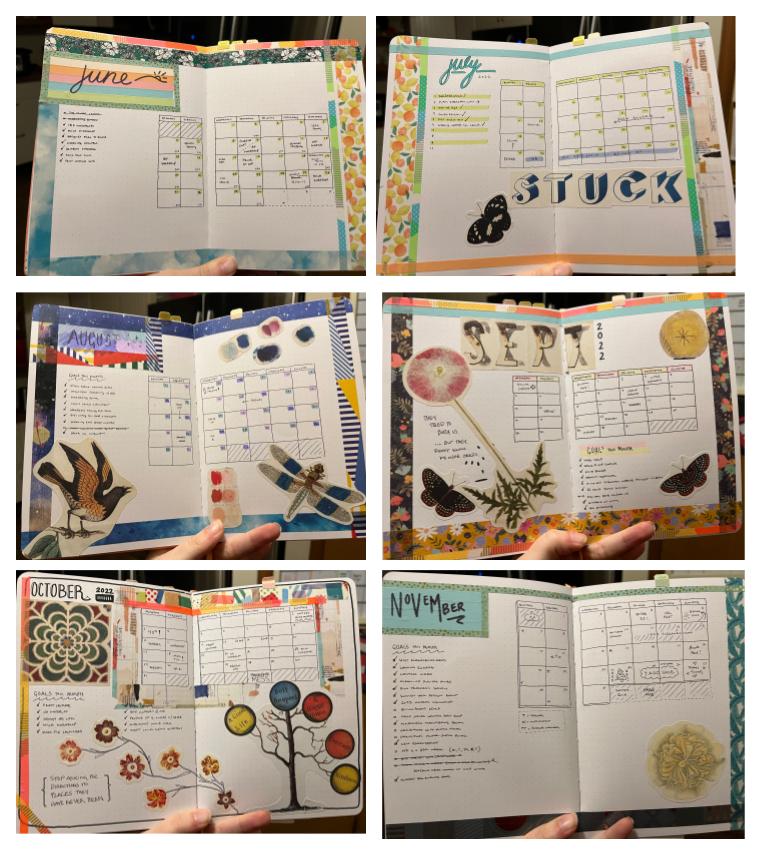

Here are some sketch note calendars I used to track a decade of my days (2020, 2019, 2015, 2014, 2013) and a picture of the time I broke Google docs by making an hour by hour spreadsheet of an entire year that was labeled and color coded.

I currently have several calendars that I keep up to date as part of my care system. Each calendar has a well-defined use so that when a time-bound task or event comes into my orbit, I know how to file it away for the best chance of my brain recognizing it as it approaches.

Google Calendar – This calendar is the source of truth for my appointments, as well as anything with a due date in my life. It is where my work and personal schedules are and where I block out important self-care and other-care tasks I am committed to prioritizing. I also use Calendly connected to Google Calendar to optimize other people’s access to my time. I have days/times I do and do not take different types of meetings so I can best support my creative work which requires deep focus and not a lot of context switching.

Monthly calendar – I draw a calendar in my journal to capture major goals and events for the current month for both my personal and work life. I spend time every month making this into something I want to look at everyday for a whole month. I use colors and imagery to fit the mood of my current season and have found this activity to be a great way to connect with time as a material, and see how much I am attempting to make future me do.

Family Calendar – We have a 9 weeks at a glance calendar drawn on a whiteboard in our kitchen. We use it to capture events and any other changes to our regular schedule.

This Week Calendar – We have another whiteboard showing just a single week with any weekly task reminders, our family to-dos, my son’s school calendar and a dinner plan for that week.

“Wow, that’s a lot of calendars!” “Why not just one calendar to rule them all? Why not just make it all digital, there are apps for that?”

This, dear reader, is the information architecture part. IA isn’t about finding the right single tool to serve the need. It is about understanding the way a user (me!) wants or needs to do something, and then structuring that thing to serve that user (still just me!) in whatever medium would best serve their intention.

I find the compartmentalization of calendars for more specific uses helps way more than a single calendar that should just do all four jobs or an app that promises the same. And believe me, I have many failed apps experiences where I half-onboarded under the promise of that should.

Over time I have identified that messy whiteboard calendars prominently displayed in my living space and in my journal that I look at everyday are way more effective for me than any app or screen. These physical calendars are better at forcing my workaholic brain to remember there is only so much time in a month, week, or day. But I also know that without a digital calendar of the critical time-bound stuff I would be toast! This combination of multiple calendars to support discrete tasks has been life changing for me.

My care system’s use of calendars evolves and changes with the season and I expect that what I need from calendars will keep changing as I change.

Goal Accountability & Task Tracking

For several years I have been meeting on a weekly basis with an accountability partner. They are in a similar but not the same area of professional focus as me, and we have very different goals with complimentary skills the other needs the balance of regularly.

We have formed a level of trust enough to share both our personal and professional goals, as well as habits and tasks we want to be held accountable on. This allows for a more whole approach to looking at goals.

Over the years, we have continually iterated on the information architecture of the goal worksheets we each use to keep one another, and ourselves accountable. Each of us has slighted different needs, and have made our worksheets reflect that. After many iterations, here is the system I am currently using:

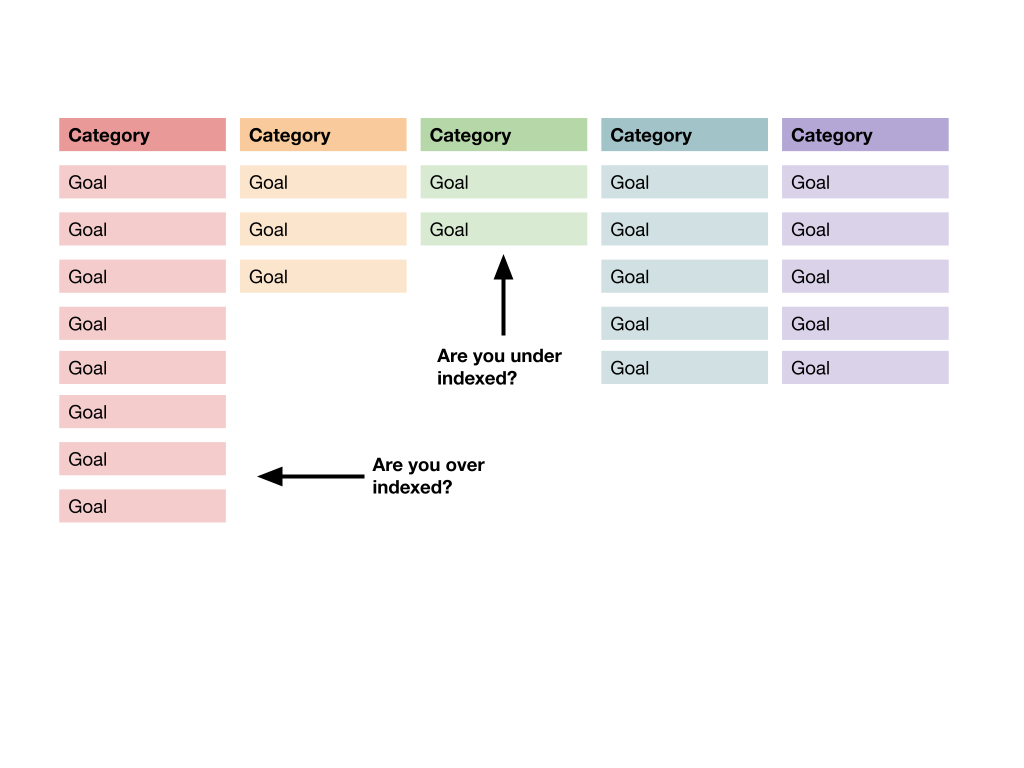

Annual Goals: I started my goal setting this year by identifying areas of my life that my goals should support. Then I used them as categories to catch and provoke like-intentioned goals.

Some examples from my list are “Stay Healthy and Well”, “Be a Good Mom and Partner”, “Make Things” and my personal favorite label for a goal bucket this year … “Make the Donuts”.

My accountability partner and I have found that this exercise of categorizing our goals allows us to see areas of our life where we are over- or under-invested. It has also encouraged us to spread our short and long term energy more evenly across categories.

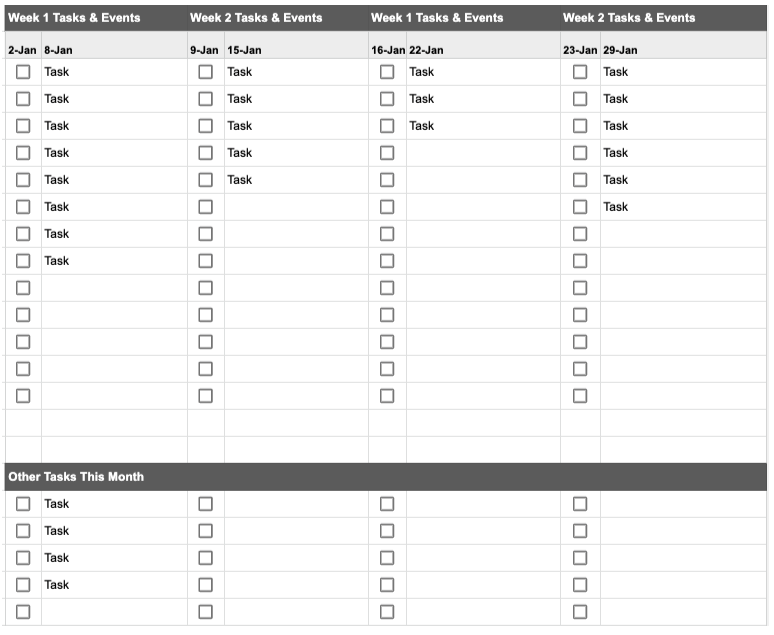

Monthly / Weekly Tasks: Every month I look at my annual goals, my to-do list from last month, the random scraps of paper all over my house, my inbox, the doom piles of paper on all surfaces and my myriad of calendars to create two sets of to-do lists for the month ahead (and ONLY the month ahead)

- A week-by-week list of tasks and events that are time specific

A catch-all list of tasks that are NOT time specific

As the weeks go on, I can add tasks as they come up and file them directly into a week, or just leave it for sometime this month.

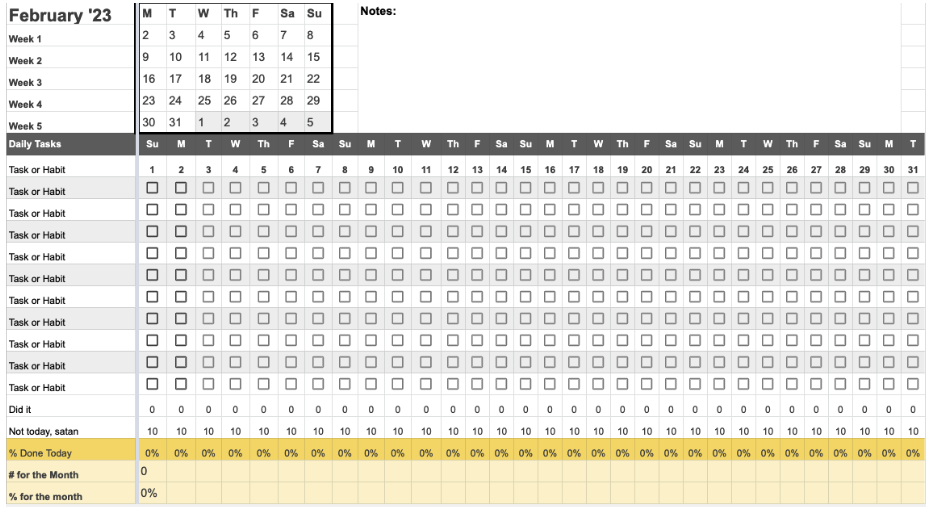

Daily Repeatable Goals: Every month I also create a check-list of the repetitive daily habits, chores or tasks that I want to track or integrate into my current daily routine. This keeps me accountable to specific self-care routines that I need to support my bigger goals.

Also the dopamine hit I get from doing mundane, healthful tasks makes my brain very happy and is a great warm up towards working on bigger, harder to check-off the list goals. Yes – you read that right, I am an adult person who will squeal with joy because I get to check off that I brushed my teeth.

Whatever. Works.

Sounds like too much? Good thing this is not for you. It’s for me.

This post is not about telling you how to organize your calendars, or track your goals. I am not selling you a system or template to organize your life. This is only one example of how thoughtful attention towards the systems around us can improve our lives.

This same system could be another person’s literal version of hell, and I get that. You do you. If you let it, the ultimate longitudinal study is on ourselves.

I find categorizing and breaking down my goals into tasks over time to be majorly life-giving. It allows me to monitor my commitments, but more importantly to make sure I find time for rest and play. It forces me to take my goals one day, week or month at a time, instead of keeping them all front-of-mind all the time.

How to Improve the IA of Your Care System

There is a framework created by Richard Saul Wurman called L.A.T.C.H. which does an excellent job of demystifying the concept of classification by providing five basic ways one can classify anything.

L.A.T.C.H stands for those five ways:

- Location

- Alphabetical

- Time

- Category

- Hierarchy

There are a ton of useful explanations out there for L.A.T.C.H as it applies to organization in general so if that is of interest to you, this video is one of my favorites.

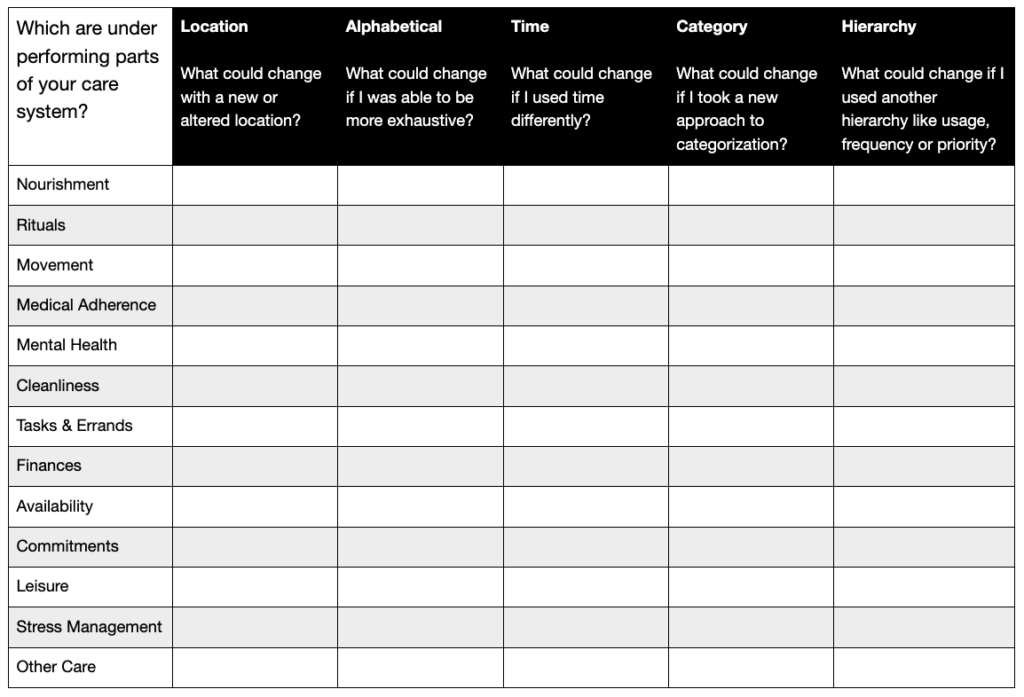

For the purpose of applying information architecture principles to your own care system I turned the principles of L.A.T.C.H into a matrixed list of questions to ask yourself when looking to improve a part of your own care system.

If Location

What could change with a new or altered location?

Let’s say you are finding that you are not looking at the to-do list app on your phone that you thought should help you with task management. This might be a location problem.

This part of your care system might be improved by a new or altered location. For example you could try making you to-do list outside your phone (new location) or a more prominent location for the app on your phone home screen (altered location)

When it comes to applying IA lessons of location – there are two important concepts to highlight:

Placemaking is how we influence a space to be perceived as a place. Whether we want to create a physical or digital experience, there are decisions we can make about location that really matter. An example of placemaking in self care might be setting out all your vitamins and medicines with your favorite water bottle on your kitchen counter before you go to bed. I started doing this and it was critical for my medication adherence. Similarly, I carved out a special place to journal each morning – and journal more mornings as a result. There are big and small ways we can change our spaces into places that can better support our goals.

Compartmentalization is taking a big thing and making it smaller and then putting it into different compartments that support new needs. This might be as minor as putting a smaller bag of essentials that you find yourself searching through your large bag for everyday, or as major as telling your team that you need a meeting free day every week to meet their needs for your work. Compartments are boundaries, and we need them.

If Alphabetical

What could change if you were about to be more exhaustive?

Let’s say that you are feeling really overwhelmed with everything you need to attend to, or accomplish for a long term project. This feeling might even keep you up at night or distract you from the joy of your everyday life. This is an issue that might be solvable by allowing yourself to get “exhaustive” in externalizing that mess. I put this under the IA principle of alphabetical because this part can feel like we have to get everything out, and make sure we cover it all A to Z.

This part of your care system could use some exhaustion, especially since it is already exhausting you.

In a case like this you might benefit from making a list, and then perhaps turning it into a matrix. For example you could partner with someone to write down all the random worries and tasks that you have right now about your personal life, work life, latest project etc. I suggest a partner instead of list-making solo to keep you focused, fair and hopeful. The result is a list of all the “things you feel that you need to think about” – which can work wonders for one’s mental health just to externalize.

If you are still feeling overwhelmed by the list, you can further exhaust it by adding more about what you know about each task. You might add how long it takes, how expensive it is, how urgent or important it feels, if it is repeatable or perhaps delegatable. Psst, that’s called adding metadata if you’re talking fancy.

Here are a few of the most common information architectures for allowing ourselves to get exhaustive:

Lists are one of the best ways for us to take things out of our brain so we can judge them more objectively, and see patterns that might help us make sense of them. For example my husband and I recently spewed onto a spreadsheet all the annual, bi annual, monthly, and weekly house maintenance and childcare tasks we are collectively responsible for. When we listed it all out, what felt like a million ambiguous things was really less than 25 actual objectively measured things we could just plan to humanely tackle together.

Matrices/Matrixes are lists with metadata about those items that we can use to sort, filter and measure the items on the list. For example once we had our list of tasks we added a column to delegate who was in charge of each and if there were set times they needed to be done, vs. tasks that could slide around to fit where they could. Once we had that kind of metadata on each task we could much more easily see if there were imbalances between us, tasks that weren’t getting done because they lacked ownership as well as obvious signals as to when each task should be tackled.

If Time

What could change if you use time differently?

Let’s say you are feeling like everything is going way too fast, or too slow. This is the feeling that time is not on our side. Perhaps that feeling is in the way of getting to your goals, or perhaps it is keeping you from the basics of taking care of yourself.

This is a problem that might be good to look at through the lens of time. How could this part of your care system change if you used time differently? This can start as a thought exercise, but also quickly change how you actually decide to use your time.

My perspective is that time is one of the most important (and ambiguously finite) materials in this universe, and our use of it determines a lot about our life. If you haven’t observed your use of time, you might have a part of your care system that could be helped by a different approach to time.

Let’s say that you want to write a book, or make a short film or some other creative or commercial pursuit but you feel like time is flying by with no progress because you never have enough time to work on it. In a case like this, paying extra attention to how time is being used (and perhaps lost) might be a good place to start.

If you truly don’t know where the time goes, you might track your use of time for a week and see where it all goes. If you are looking for insight into what tracking your time honestly takes (or how much time I spent watching TV in 2014), I wrote a talk about the year I spent deeply tracking my time in an effort to combat burn-out and workaholism.

If you have a predictable enough schedule, try drawing out a week on paper and then color in the times that are already committed to things like sleep, commuting, work, self-care and other-care. Use a different color for each category of time that’s important to you.

How does the balance of those categories feel? Does it match your intentions? Can more time be found? How much free time do you have left? What would be realistic to expect of yourself with that amount of time? All of these questions are unlocked when we make time a visual tool.

Calendars are a way to visualize time in a finite and objective way so we can better wrap our minds around how much time we (hopefully) have and/or how much time we need. For example if you are taking on a large project, it is almost always a good idea to take out a calendar to establish some milestones, and checkpoints – especially if other people are involved. The ambiguity of creative work can greatly benefit from use of a calendar to start to tame all that uncertainty into something usable, timeboxed and perhaps even hopeful.

Schedules are set times of the day, week, month or year that you plan to do a certain thing or set of things. Schedules are a way of life I first started to lean on as a parent and then later as a self-employed creative person. For example, my husband and I have an hour-by-hour breakdown of “who’s on first” when it comes to our kiddo. We started doing this when he was an infant, and honestly I don’t know when it will stop being helpful. Rather than have a “default parent” we have parent-on and off hours. During my parent-on hours, I am the first at the scene for any needs our kid has. I am also his playmate, private chef (read: snack bitch) and tantrum-handler for him during those times. It is a set weekly schedule that only moves when something disrupts normalcy. We have found that this system ensures an even-parenting divide, but mostly it’s the best way for each of us to get some actual downtime as well as uninterrupted work-time, and self-care time.

Time Blocks are allocated times to do a certain type of thing. For example, because I work alone, I have found that I need to give myself some structure for my work time otherwise I would be lost in the sea of scrolling. I find I have to time-box tasks that either make me anxious, or trigger my perfectionism or let’s be honest, both. So I have time blocks weekly for things like “social media” and “email” because either or both could eat my whole week if I let them. I also have a set time each weekday that I write, as well as times I will/will not take meetings.

Like most things as rigid as what I am describing, it only works about 80% of the time. In fact while writing this piece, my husband and son both got the stomach flu and my schedule was upside down for a few days. There are some weeks I have to drag those time blocks around my google calendar into some pretty strange arrangements to make the bare minimum work, but I feel more empowered having those blocks as a material I can objectively move (and then theoretically get off my mind and heart)

If Categorization

What could change if you took a new approach to categorization?

Let’s say you are trying to organize a messy part of your care system. Maybe you made a list, but still have a big list of un-homed tasks you have to fit in somewhere and prioritize against one another. This is an instance that might be worth looking at through the lens of categorization, similarly to how I tackled my annual goals.

For example you could look at that list of tasks and start to think of them in unique categories like “have to leave the house” or “requires human contact” or “things I wish I did at a certain time but don’t” or “things I need a car for” – or if you are my husband “things to do when you have your outside clothing on” or “things to do when you have the lawn equipment already out”

By putting things into these custom categories, we can start to find groupings that might make for a good routine when put together, or perhaps a group of things that can be tackled together when you are in a certain mood or circumstance.

Routines are strings of tasks we put together into a sequence. If you are neurodiverse like me, routines can be a blessing and curse. I can make and stick to a routine for an indeterminable amount of time, and then it eventually breaks and I need a new routine. By looking at my routines as information architectures, I have been able to see how stopping my routine or changing it is not a failure of me or of the system – it is just my system signaling it needs iteration to serve my intentions which have changed. It also doesn’t negate that routines are helpful AF while I have them, however fleeting. I like to think of them like momentary helpers to get me through a season, not aspirational beings I think I should be.

Moods & Circumstances change our ability to show up for ourselves and for others. The more we keep the brutal reality of being human in mind as we construct our care system the stronger that system will be in the long run. I find that using our understanding of potential changes to our mood or circumstance can be a great way to customize things like time blocks and routines. For example you might combine a bunch of errands and schedule them for a certain time together. Or you might have a list of ideas that you keep for when you feel creative. My husband and I ended up combining the post office errands for both our eCommerce businesses based on talking about our repeat tasks through the categorization of circumstance. We both hate going to the post office, and felt like we constantly had to go. Now with just a few tweaks to the timing of our businesses we each only go twice a month.

If Hierarchy

What could change if you used a new approach to hierarchy?

Let’s say you have a part of your care system that feels out of balance. Maybe you feel like you have too many things in a cabinet or storage space or maybe you made a list of care tasks for your home and didn’t like the balance you saw between you and other household members. Or perhaps you realized you needed to do a seldom-done task way more often to reach a certain goal. These are problems with the concept of hierarchy at the center.

In a case like this it can be empowering to think about what the impact would be if you paid attention to aspects like usage, frequency or priority.

For example in the case of the messy cabinet or storage space you might think about the use of the space and what priority each item should have given its frequency of use.

By thinking about things within a group in relation to one another, we can make hierarchy work for us.

The opposite of hierarchy is heterarchy, which means to keep all things on the same level. This approach can also be beneficial in some circumstances. For example if we want to throw all our shoes into a single basket. But sometimes hierarchy is helpful, in this example that might mean throwing the oft-worn shoes in a basket and putting the frequently used ones on a rack.

There are three aspects of hierarchy that I find to be the most useful in my care system:

Usage is paying attention to the ways in which we actually live. It is easy to get lost in a sea of perfection and set up your whole care system for a person who is not in fact you, living your life. Many aesthetic solutions, the likes of TikTok Restock and GRWM videos, are not set up to let you succeed in actual living. They are in fact more setup to help you never feel like you measure up to an ideal standard you feel you should. By looking at your actual usage of items in your life, or tasks in your days you can change the way your systems are set up – and see more alignment with your intentions. A good example might be in a closet. Sometimes we place a priority on categories, when it is actually usage we should be organizing around. In my life now I wear mostly very casual clothing, house clothes or gym clothes and I live in a warm climate. But until quite recently, my closet was set up for someone working a business casual job in a cold climate. By rearranging my closet around my actual usage I saved a ton of time, sure. But I more importantly saved myself from that subtle feeling of not belonging that was lurking in my closet every morning.

Priority is paying attention to how important we believe things in our life to be. Similar to usage, it is easy to get lost in a sea of should when it comes to priority. If we aren’t thoughtful and specific about what we prioritize in our life, we might end up with someone else’s priorities masquerading as our own. When I first had my son, I was one of those people who thought they could keep a tidy and organized living space while also raising a tiny being learning to be human. That was me prioritizing my own preference for things to be just-so and orderly. It was also me secretly prioritizing what society expects from me in terms of “keeping a home”.

In reality, the clutter of my kiddo doesn’t really impact my day (except when the legos make it into the walking paths, those suck). My point is that it wasn’t until I changed my priorities that I could align my care system with what I actually wanted, which was to provide a safe and welcoming place to grow up, a place that prioritizes play and self expression over order and perfection. So now I spend a whole lot less time tidying and a whole lot more time being able to play and be present with my kid.

Frequency is paying attention to how often we do a task or encounter a circumstance. Frequency is the easiest and most objective of these three types of hierarchy, but don’t let that fool you into thinking it is easy to get right. Frequency can also linger too long in the land of should, telling us that we should be doing something more or less often. In reality, for our care system to actually care for us, we have to give in to the reality of our frequency, not the idealized version. Meal planning is something that I can easily relate past issues in my care system to frequency. I used to think about our dinner meal plan as something we should be following every night. By overestimating our frequency of need, we ended up with too many groceries we didn’t use when we got tired of cooking, or too much leftover cooked food when we could stick to it. By recognizing the frequency needs of this daily task, my husband and I have aligned on a dinner meal plan that includes “leftover night” – we also don’t plan for cooking more than 4 dinners in the 7 days. For now this is a good balance, and one I am sure will keep changing as our family’s needs change.

How to Take Care of Any Sensemaker

In my book How to Make Sense of Any Mess, I outline a six step IA process. To wrap up here are the points we went through as they might apply to improving your own care system.

1. Identify the Mess: Make a list of the areas of your care system that might be weak or ill-aligned with your intentions. Don’t focus on solving them, just make a list.

2. State Your Intent: Review your list and decide how this reflects (or doesn’t reflect) your intentions or values. Based on this exercise, make a new list of the things you intend to accomplish and how a stronger care system might help that.

3. Face Reality: Revisit those intentions through your own reality. What do you have the resources for? What is rigid vs. flexible in your world? What can be changed in actuality? This is the step where we want to really address the epic power of “should” and adjust our intentions according to what we can actually accomplish.

4. Choose a Direction: Even with a list of intentions that are realistic in hand, we still have lots of decisions to make about which direction to take things. Will your writing goal get filled with late nights, a mid day habit or perhaps in the early mornings? Will your commitment to physical movement be an exercise class or attending a dance party regularly? Will your commitment to prioritize rest mean an earlier bedtime or a midday nap or a sleep study? There are many ways to accomplish the same intention and this is the right time to start to narrow it down. This is also a time to experiment and iterate if a direction is not yet clear. If you don’t know yet what might work best, try a few.

5. Measure the Distance: Once again be honest with yourself about how big these proposed changes to your care system are and make a realistic plan for enacting those changes. The toxic world of the self-care industry too often revolves around a perfect end state, or adherence to someone else’s system that should work. But the real work of taking good care of yourself is almost all in admitting there is no end state, only steps toward and steps away from what we intend.

6. Play with Structure: In the above I outlined three taxonomies that I hope you find useful when playing with your structure.

A list of common areas of a care system:

- Nourishment

- Rituals

- Movement

- Medical Adherence

- Mental Health

- Cleanliness

- Tasks & Errands

- Finances

- Availability

- Commitments

- Leisure

- Stress Management

- Other Care

A list of questions to ask if seeking a change in one of those areas:

- Location: What could change with a new or altered location?

- Alphabetical: What could change if I was able to be more exhaustive?

- Time: What could change if I used time differently?

- Category: What could change if I took a new approach to categorization?

- Hierarchy: What could change if I used another hierarchy like usage, frequency or priority?

A set of five common tools to experiment with as you play with the ideal structure of your own care system:

- Calendars

- Task/Goal Tracking

- Schedules

- Routines

- Time Blocks

A set of critical aspects to pay attention to when making decisions about how to structure your care system.

- Compartmentalization

- Placemaking

- Moods & Circumstances

- Usage

- Priority

- Frequency

None of these is by any means a complete list, but I hope they can get you started as you play with potential structures to better support your care intentions.

7. Prepare to Adjust: Even the most thoughtful and attentive to-do list, medical adherence routine, closet organization schema, or meal planning system will eventually need to change to meet the needs of a real person over time. Because we are never constant, and always evolving. It’s easy to judge ourselves and not our systems when they break down in the face of changes in our real lives. This final step is to remind you that you are solving today’s problem, and to be ready to accept that those needs will change again and again.

–

Thanks for your time.

📬If you found this to be of value, I would be so appreciative if you sent this piece to someone else who might also find value in it.

✍️If you enjoyed my thoughts on this topic you might also enjoy reading about me realizing someone else was setting my priorities for me or about the common messes I hear about most (Spoiler alert: life messes was number 1!)

📚If you are looking to dig deeper into learning about information architecture, I can recommend my two books How to Make Sense of Any Mess & Stuck? Diagrams Help as well as this list of resources.

🤓If you are already IAware, and are ready to go from curious to confidently practicing information architecture in your own context (self care as an example) consider becoming one of my students by registering for The Practitioner’s Guide to How to Make Sense of Any Mess.

💌If you want to keep up with the latest from me, join my monthly email list.